Native religion in Roman Britain: the evidence

What was the ‘native’ religion?

Aldhouse-Green provides us with perhaps the best definition of ‘native’

cults, deities and sanctuaries, as being those ‘that apparently had their genesis

in the cosmological systems and paradigms of western Europe outside the Mediterranean

littoral’ (2004, 193). An examination of the evidence shows that the nature

of the Celtic/native religious beliefs in Britain during the time of the Romans

can be broken down further into one of three types:

- truly ‘native’, i.e. originating in the British pre-Roman Iron Age,

and continuing to be worshipped by the Romano-British populace

- ‘native’ but originating during the Roman occupation of Britain

and worshiped by the populace

- brought into the province by non-British Celts, who could be either

civilians, i.e. traders/merchants, or the military.

Celtic religion was expressed as a belief in ‘the spirits of nature. Sea

and sky, mountains, rivers and trees…the sun, the source of heat and light,

and the moon, the measure of time…’ (Birley 1964, 136). All were thought to

be endowed with powerful spirits, as were certain animals and birds, seen as

having impressive attributes, and all deserving of worship by prayer and sacrifice.

Henig (1984) further emphasises this connection between natural features and

the divine world and claims that place-name evidence suggests that rivers in

particular received names long before the Celtic language was spoken, i.e.

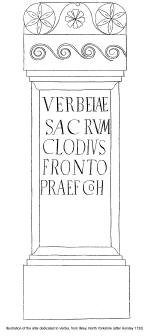

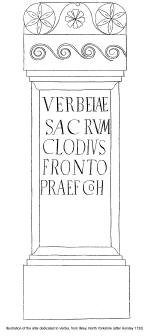

the Thames may have been so named in the Bronze Age or earlier (ibid. 17). Further examples of the worship of these personified natural features include

Verbia, meaning ‘winding river’, attested on an altar at Ilkley, North Yorkshire

(RIB 635). This connection with water - the veneration of rivers and watery places,

especially bogs - is also attested in the numerous offerings of precious objects.

The

earth itself was also thought to be sacred. Shafts were sunk into the ground

in the Bronze Age and became more frequent in the Iron Age and Roman periods.

Evidence of sacrifices in these pits, along with the presence of great timbers,

suggests a symbolic sexual penetration of the earth thus constituting fertility

magic.

Celtic religion was expressed as a belief in ‘the spirits of nature. Sea

and sky, mountains, rivers and trees…the sun, the source of heat and light,

and the moon, the measure of time…’ (Birley 1964, 136). All were thought to

be endowed with powerful spirits, as were certain animals and birds, seen as

having impressive attributes, and all deserving of worship by prayer and sacrifice.

Henig (1984) further emphasises this connection between natural features and

the divine world and claims that place-name evidence suggests that rivers in

particular received names long before the Celtic language was spoken, i.e.

the Thames may have been so named in the Bronze Age or earlier (ibid. 17). Further examples of the worship of these personified natural features include

Verbia, meaning ‘winding river’, attested on an altar at Ilkley, North Yorkshire

(RIB 635). This connection with water - the veneration of rivers and watery places,

especially bogs - is also attested in the numerous offerings of precious objects.

The

earth itself was also thought to be sacred. Shafts were sunk into the ground

in the Bronze Age and became more frequent in the Iron Age and Roman periods.

Evidence of sacrifices in these pits, along with the presence of great timbers,

suggests a symbolic sexual penetration of the earth thus constituting fertility

magic.

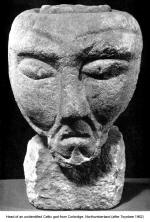

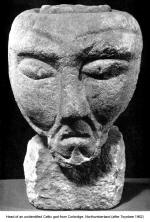

The cult of the head also formed part of the Celtic belief system. Human

heads were seen as totems of power. A head could be severed from an enemy in

battle and yet retain life independent of the body. The head in Celtic imagery is often shown stylised, with almond shaped eyes, long nose, and a slit mouth:

whilst the head on divine images is often shown with horns or antlers, reflecting

another belief – that of the Img38.htm.

The cult of the head also formed part of the Celtic belief system. Human

heads were seen as totems of power. A head could be severed from an enemy in

battle and yet retain life independent of the body. The head in Celtic imagery is often shown stylised, with almond shaped eyes, long nose, and a slit mouth:

whilst the head on divine images is often shown with horns or antlers, reflecting

another belief – that of the Img38.htm.

Specific sites of native worship would have had their own individual rites

and ceremonies, for the power of Celtic deities appears to have been very much

tied to specific locations.

Interpretatio Romana

‘The practice of conflating Roman with indigenous god-names was endemic

within the Roman Empire, and should, perhaps, be read as a mechanism for the

negotiation of socio-economic identities which may have been presented in terms

of equal (or near equal) partnership between romanitas and local tradition’ (Aldhouse-Green 2004, 201).Aldhouse-Green points out that

it is often difficult to distinguish between the ‘native’ British deities who

have undergone hybridisation (and are hence

termed Romano-Celtic) and those which have remained ‘native’, being entirely

Celtic in concept (1983, 51). Two examples of this are Sulis Minerva and Coventina.

At Bath (Aquae Sulis) in Western England

Roman engineers transformed a spring, possibly a focus of worship in the Iron

Age, into a great ornamental pool, probably embellished with statues and enclosed

in a grand building. Beside it they built a temple of Mediterranean type and

a magnificent set of mineral baths lay next to the temple and spring. Sulis

was equated with Minerva and the names were used together and interchangeably.

Coventina was another water-goddess .

Her shrine outside the Roman fort of Carrawburgh was excavated in the nineteenth

century. Her name is Celtic but she was not equated with one of the great deities

of the Roman state. On inscriptions she is addressed as a nymph, and is portrayed as such on sculptures. She attracted dedication from soldiers of all ranks. Near to her shrine was

a mithraeum, and also a small open-air shrine to the nymphs and the Genus Loci, and the dedicator there, a prefect, obviously saw the nymphs as separate from

Coventina. It was common for groups of shrines to exist alongside each other,

each with a separate deity having its own title and its own ceremonies. Extreme

localisation, such as this, came about because people were anxious that the

shrine of every divine power received its due. Indeed, anxiety appears to have

invaded the sleep of ordinary people as an altar found beside a spring at Risingham

records ‘Forewarned in a dream, the soldier bade her who is married to Fabius

to set up this altar to the Nymphs who are to be worshiped’.

Coventina was another water-goddess .

Her shrine outside the Roman fort of Carrawburgh was excavated in the nineteenth

century. Her name is Celtic but she was not equated with one of the great deities

of the Roman state. On inscriptions she is addressed as a nymph, and is portrayed as such on sculptures. She attracted dedication from soldiers of all ranks. Near to her shrine was

a mithraeum, and also a small open-air shrine to the nymphs and the Genus Loci, and the dedicator there, a prefect, obviously saw the nymphs as separate from

Coventina. It was common for groups of shrines to exist alongside each other,

each with a separate deity having its own title and its own ceremonies. Extreme

localisation, such as this, came about because people were anxious that the

shrine of every divine power received its due. Indeed, anxiety appears to have

invaded the sleep of ordinary people as an altar found beside a spring at Risingham

records ‘Forewarned in a dream, the soldier bade her who is married to Fabius

to set up this altar to the Nymphs who are to be worshiped’.

The ‘native’ deities

Seventy Celtic deities are known from Britain, and of these twenty-one

are also known on the Continent (see table, and selected discussion below).

Occasionally where the name of the sprit was not known, the dedication would

be just to the ‘genius’ or spirit of the place.

| Deity name: |

Known only in Britain |

Known in Britain and on

Continent |

Evidence: |

|

Abandinus |

Yes |

|

Godmanchester (Britannia 4,

(1973), 325, no. 4) |

|

Ancasta |

Yes |

|

RIB 97 (Bitterne, Hants.) |

|

Andate |

Yes |

|

from Cassius Dio, 62, 7, 3. Poss.

also equated with Nike=Victoria |

|

Andraste |

Yes |

|

from Cassius Dio, 62, 6, 1-2. |

|

Antenociticus |

Yes |

|

RIB 1327, 28 & 29

(Benwell) |

|

Apollo Anextlomarus |

|

Yes |

RIB 1162 (Arbeia) |

|

Apollo Cunomaglus |

Yes |

|

West Kington, Wilts (JRS 52 (1962),

191, no. 4) |

|

Apollo Grannus |

|

Yes |

RIB 2132 (Inveresk) Two cult centres:

i) Faimingen (Raetia), ii) Aachen (Germania inf.) |

|

Arciacones |

Yes |

|

RIB 640 (York) |

|

Arecurius |

Yes |

|

RIB 1123 (Corbridge) |

|

Arnemetia |

Yes |

|

from Ravenna Cos. possibly Aquae

Arnemetiae at Buxton, Derbyshire |

|

Arnomecta |

Yes |

|

RIB 281 (Brough-on-Noe) |

|

Belatucadrus |

Yes |

|

various spellings. Sometimes equated

with Mars. specific W. end of HW distribution |

|

Bregantes |

Yes |

|

RIB 623 (Slack, Yorks.) |

|

Brigantia |

Yes |

|

6 insc. suggesting that she was

the special patroness of the Brigantes! |

|

Britannia |

Yes |

|

RIB 643 (York) & 2195

(Castlehill) |

|

Cocidius |

Yes |

|

sometimes equated with Mars or Silvanus

also Vernostonus. Ravenna lists a fanum Cocidi, possibly Bewcastle |

|

Contrebis |

Yes |

|

RIB 610 (Burrow in Lonsdale) but

also on RIB 600 where his name is attached as an epithet to Ialonus |

|

Coventina |

|

Yes |

RIB 1522-35 |

|

Cuda |

Yes |

|

RIB 129 (Daglingworth, Glos.) shown

as a mother goddess alongside Genii cucullati |

|

Digenis |

|

Yes |

RIB 1044 (Ch.-le-St.) & 1314

(MC3) |

|

Epona |

|

Yes |

RIB 967 (Netherby), 1777 (Carvoran),

2177 (Auchendavy) & AE1966,239 (Alcester) |

|

Hercules Saegon[tius] |

Yes |

|

RIB 67 (Silchester) |

|

Ialonus |

|

Yes |

RIB 600 (n. of Lancaster) |

|

Ioug[----] |

Yes |

|

RIB 656 (York) |

|

Ixsaosc(os) |

Yes |

|

variant spellings, from 4 bronze

rings found at Caistor = Venta Icenorum |

|

Latis |

Yes |

|

RIB 1897 (Birdoswald) & 2043

(Folksteads nr. Kirkbampton, Cumb.) |

|

Maponus |

Yes |

|

6 insc., 4 of which equate him with

Apollo (the harpist not the hunter). Possibly a female goddess assoc

with him. |

|

Mars Alator |

Yes |

|

RIB 218 (Barkway, Herts) and 1055

(Arbeia) |

|

Mars Barrex/Barregis |

Yes |

|

RIB 947 (Carlisle) |

|

Mars Braciaca |

Yes |

|

RIB 278 (Bakewell, Derbys.) |

|

Mars Camulus |

|

Yes |

RIB 2166 (Bar Hill) Well

known as god of the Remi – ILS235 (Rindern) & AE1935 (Reims) |

|

Mars Condantes |

Yes |

|

RIB 731 (Bowes); 1024 (Piercebridge) & 1045

(Ch.-le-St.) |

|

Mars Corotiacus |

Yes |

|

RIB 213 (Martlesham, Suffolk) |

|

Mars Lenus |

|

Yes |

RIB 126 (Chedworth) & 309

(Caerwent) |

|

Mars Loucetius |

|

Yes |

RIB 140 (Bath) |

|

Mars Medocius |

Yes |

|

RIB 191 (Colchester) |

|

Mars Nodens |

Yes |

|

insc. on bronze and lead from Lydney

the centre of the cult |

|

Mars Ocelus |

Yes |

|

equated with Mars Lenus (see above),

also on RIB 310 (Caerwent) & 949 (Carlisle) |

|

Mars Olludius |

|

Yes |

RIB 131 (Custon Scrubs, Bisley,

Glos.) |

|

Mars Rigas |

Yes |

|

RIB 711 (Malton) |

|

Mars Rigisamus |

|

Yes |

RIB 187 (West Coker, Somerset) |

|

Mars Rigonemetes |

Yes |

|

insc. from Nettleham, Lincs. (JRS

52 (1962), 192, no.8) |

|

Mars Toutates |

|

Yes |

RIB 219 (Barkway, Herts.) & 1017

(?Cumberland) |

|

Mars Vellanus |

|

Yes |

on 309 (see above), where the god

Marc Ocelus is given the epithet Vellaun(us) |

|

Matres |

|

Yes |

approx. 60 dedications. Many have

further definition incl. Alatervae, Campestres, Communes, Domesticae,

Ollototae, Parcae, Suae, Suleviae & Transmarinae, plus 5 Matres of various people. |

|

Matunus |

Yes |

|

RIB 1265 (High Rochester) |

|

Mogons |

|

Yes |

and various other spellings! |

|

Mounus |

|

Yes |

thought to be a misspelling of Mogons,

but also known from Gaul, CIL XIII 10012, 19 (samian ves.), ded. to Mouno. |

|

Nemetona |

|

Yes |

from RIB 140

(Bath) alongside Mars Loucetius (see above) |

|

Ratis |

Yes |

|

RIB 1454 (Chesters) & 1903

(Birdoswald) |

|

Rioclates |

Yes |

|

insc. from somewhere in Cumberland? |

|

Saitada |

Yes |

|

RIB 1695 (Beltingham) |

|

Setlocenia |

Yes |

|

RIB 841 (Maryport) |

|

Silvanus Callirius |

Yes |

|

RIB 194 bronze plate (Colchester) |

|

Silvanus Cocidius |

Yes |

|

Cocidius equated with Silvanus on RIB 1578

(Housesteads) and 1207 (Risingham) |

|

Sucellus |

|

Yes |

silver ring from York insc. deo

Sucelo |

|

Suleviae |

|

Yes |

4-5 insc. one of which is Matres

Suleviae. Ded. by civilians! |

|

Sulis |

|

Yes |

all insc. from Bath, except for

CIL XIII 6266 from Alzei, suggesting that cult brought to Rhineland

from a visitor to Bath. |

|

Tanarus |

Yes |

|

from an altar found at Chester in

1653. Text now unreadable! |

|

Tridamus |

Yes |

|

RIB 304 (Michaelchurch, S. of Hereford

–not a Roman site!) |

|

Tuetela Boudriga |

|

Yes |

single altar found in Bordeaux is

only evidence, BUT as it is ded. by a certain Lunaris, a poss. trader

from York. May have been shipped there as ballast |

|

V[------] |

Yes |

|

fragmentary insc. from Wroxeter

(JRS 52 (1962), 192, no. 9) |

|

Vanauntes |

Yes |

|

RIB 1991 (nr. Castlesteads) |

|

Verbia |

Yes |

|

RIB 635 (Ilkley) |

|

Vernostonus |

Yes |

|

RIB 1102 (Ebchester), equated with

Cocidius |

|

Veteris |

Yes |

|

many variations in spelling. More

of an E. end of HW dist. |

|

Vinotonus |

Yes |

|

RIB 732 & 733 from

two shrines on the moors S. of Bowes and poss. 3 others 735/6/7. |

|

Viridius |

Yes |

|

alter found in 1961 at Ancaster

(JRS 52 (1962) |

|

Mercurius Andescovivoucus |

Yes |

|

RIB 193 (Colchester) found in 1764

(now lost!) |

Comparison study – the villa region of Western England and North-east

England

In Western England a concentration of sculpture and inscriptions can be

seen to correspond to the richer villa zone, while in North-east England, especially

on the northern frontier, the native deities appear to have distinct distributions,

possibly relating to the nature of the military presence. In both of these

areas native deities predominate, overshadowing the official state religion,

however, a definite distinction could be made between the military zones and

the civilian, where in the latter the Roman and native gods appear to be ‘harmoniously

intertwined’, while in the former ‘a sentina numinium, a kitchen-midden of all sorts of cults heaped up from all quarters of the Empire’,

prevailed (Haverfield 1923, 73).

The villa region of Western England

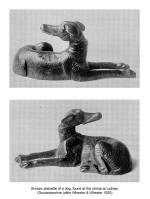

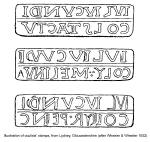

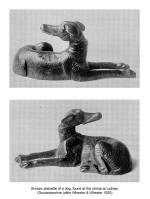

An example of a wholly British deity is Nodens, or Nodons.

His main sanctuary was at Lydney (Gloucestershire) on the river Severn, where

he is mentioned either alone or equated with both Mars and Silvanus. He was

essentially a hunting god, but was also associated with water and healing.

His large temple complex was centred on a therapeutic spring, which also contained

a number of buildings including a dormitory. There are no representations of

him in human form and the finding of representations of dogs from the site may suggest that he either took that form or that he was attended

by a dog (similar to the healer god Aesculapius). Finds of oculists’ stamps

(collyrium or salve stamps) confirm his aspect of healing. His temple complex was not founded before the

third-century AD and has been associated with a re-emergence of cult activity

in the southwest dating to late third and fourth century.

An example of a wholly British deity is Nodens, or Nodons.

His main sanctuary was at Lydney (Gloucestershire) on the river Severn, where

he is mentioned either alone or equated with both Mars and Silvanus. He was

essentially a hunting god, but was also associated with water and healing.

His large temple complex was centred on a therapeutic spring, which also contained

a number of buildings including a dormitory. There are no representations of

him in human form and the finding of representations of dogs from the site may suggest that he either took that form or that he was attended

by a dog (similar to the healer god Aesculapius). Finds of oculists’ stamps

(collyrium or salve stamps) confirm his aspect of healing. His temple complex was not founded before the

third-century AD and has been associated with a re-emergence of cult activity

in the southwest dating to late third and fourth century.

Two native cults that appear in both regions but which are perhaps more

common in Western England are those of the Deae Matres – one of the many forms of Mother-Goddesses, and the Genii cucullati – curious representations of three dwarves wearing the Gaulish hooded cloak. The Deae Matres are connected with fertility and are often depicted in triplicate as a group

of female figures carved in simple stone relief, either nursing infants or

with baskets in their laps containing loaves, fruit, or fish symbolising plenty.

Single representations also occur – an example is known from Caerwent - while

a group of four was discovered in London. Depictions can also be found on bronze

and silver plaques. Their distribution includes Hadrian’s Wall, Lincolnshire

and London, but there is a concentration in Western England, notably centred

on Cirencester and Bath where they are known as the Suleviae – a name thought to be linked to Sulis – and are also possibly connected to water and healing springs. The Genii cucullati share an identical distribution to the Deae Matres, being especially common in Cirencester. Their relief carvings appear very crude

and sometimes schematised and they are associated with prosperity, well-being and fertility. In Gloucestershire

they are sometimes found accompanying the mother-goddesses, or shown carrying

eggs, and like them are also connected with ceremonies associated with therapeutic

springs, as evident at Springhead (Kent) and Bath.

Two native cults that appear in both regions but which are perhaps more

common in Western England are those of the Deae Matres – one of the many forms of Mother-Goddesses, and the Genii cucullati – curious representations of three dwarves wearing the Gaulish hooded cloak. The Deae Matres are connected with fertility and are often depicted in triplicate as a group

of female figures carved in simple stone relief, either nursing infants or

with baskets in their laps containing loaves, fruit, or fish symbolising plenty.

Single representations also occur – an example is known from Caerwent - while

a group of four was discovered in London. Depictions can also be found on bronze

and silver plaques. Their distribution includes Hadrian’s Wall, Lincolnshire

and London, but there is a concentration in Western England, notably centred

on Cirencester and Bath where they are known as the Suleviae – a name thought to be linked to Sulis – and are also possibly connected to water and healing springs. The Genii cucullati share an identical distribution to the Deae Matres, being especially common in Cirencester. Their relief carvings appear very crude

and sometimes schematised and they are associated with prosperity, well-being and fertility. In Gloucestershire

they are sometimes found accompanying the mother-goddesses, or shown carrying

eggs, and like them are also connected with ceremonies associated with therapeutic

springs, as evident at Springhead (Kent) and Bath.

North-east England

In the northern military zone, particularly along Hadrian’s Wall, the

native gods overshadow the official Roman religion and all the other Graeco-Roman

gods (Breeze & Dobson 2000, 281). There are dedications to native deities known throughout

the province, but there are many who are specific to the military zone such

as Antenociticus at Benwell and Coventina, mentioned above, at Carrwburgh,

however, three deities in particular have prolific dedications.

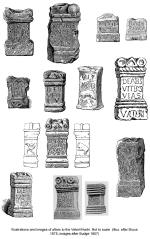

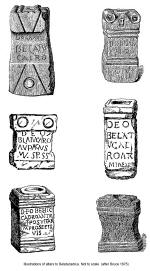

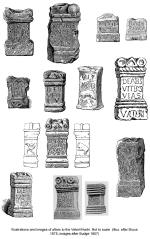

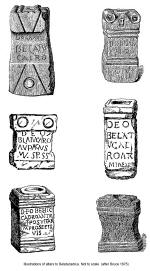

Belatucadrus, of which there are no representations, was mainly worshipped

towards the western end of Hadrian’s Wall, and at Brougham (Cumbria) in the

military hinterland. Often he is equated with Mars and his dedications usually

take the form of small altars set up by the lower ranks of soldier.

Belatucadrus, of which there are no representations, was mainly worshipped

towards the western end of Hadrian’s Wall, and at Brougham (Cumbria) in the

military hinterland. Often he is equated with Mars and his dedications usually

take the form of small altars set up by the lower ranks of soldier.

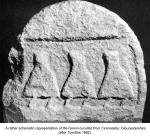

Cocidius also has a similar western distribution, and like Belatucadrus

is often equated with Mars. It is believed that his shrine was situated at

or near Bewcastle (Cumbria) – thought to be the Fanum Cocidi of the Ravenna

Cosmography. Silver plaques from the headquarters building at Bewcastle depict

a more schematised version of him, wearing full armour and holding a spear

of native type. Where Cocidius differs is that he is worshipped by the military,

often by men of superior social standing such as a legionary centurion and

equestrian officers. He is also occasionally represented, in figure form, in rock-cut shrines.

Cocidius also has a similar western distribution, and like Belatucadrus

is often equated with Mars. It is believed that his shrine was situated at

or near Bewcastle (Cumbria) – thought to be the Fanum Cocidi of the Ravenna

Cosmography. Silver plaques from the headquarters building at Bewcastle depict

a more schematised version of him, wearing full armour and holding a spear

of native type. Where Cocidius differs is that he is worshipped by the military,

often by men of superior social standing such as a legionary centurion and

equestrian officers. He is also occasionally represented, in figure form, in rock-cut shrines.

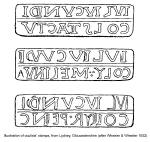

The third unique local deity is a god (or gods) known as the Vetri or

Hveteri, with a multitude of similar spellings, whose distribution is mainly

the central and eastern parts of Hadrian’s Wall, with some sites having large

numbers of dedications (16 at Carvoran, and 9 at Vindolanda). These also tend

to be in the form of small altars, dedicated by the lower classes, although

it has been suggested that the variation in spelling indicates that the deity’s

name could not be expressed easily in

the Latin alphabet (Birley 1979, 107).

The third unique local deity is a god (or gods) known as the Vetri or

Hveteri, with a multitude of similar spellings, whose distribution is mainly

the central and eastern parts of Hadrian’s Wall, with some sites having large

numbers of dedications (16 at Carvoran, and 9 at Vindolanda). These also tend

to be in the form of small altars, dedicated by the lower classes, although

it has been suggested that the variation in spelling indicates that the deity’s

name could not be expressed easily in

the Latin alphabet (Birley 1979, 107).

The military zone occupied a large part of the area associated with the

Brigantes and this territory appears to have had its own deity Brigantia: though

the distribution of her dedicationsis incoherent, mainly occurring in two distinct

regions; Hadrian’s Wall and to the north of it (i.e. Birrens); and also the

area of the Calder basin. At

Aldborough, the presumed tribal capital, there is no record of her. Her representation,

from a statue found at Birrens, was described by Richmond as ‘… a remarkable personification, which combines

in one figure the conception of a territorial goddess, with mural crown, a

wargoddess clad like Minerva but with an auxiliary regiment’s style of helmet,

a Victory with wings, and a featureless monolith representing Caelestis’ (1955,

190). On some dedications she is addressed as a water-goddess but not in the

Birrens example.

The military zone occupied a large part of the area associated with the

Brigantes and this territory appears to have had its own deity Brigantia: though

the distribution of her dedicationsis incoherent, mainly occurring in two distinct

regions; Hadrian’s Wall and to the north of it (i.e. Birrens); and also the

area of the Calder basin. At

Aldborough, the presumed tribal capital, there is no record of her. Her representation,

from a statue found at Birrens, was described by Richmond as ‘… a remarkable personification, which combines

in one figure the conception of a territorial goddess, with mural crown, a

wargoddess clad like Minerva but with an auxiliary regiment’s style of helmet,

a Victory with wings, and a featureless monolith representing Caelestis’ (1955,

190). On some dedications she is addressed as a water-goddess but not in the

Birrens example.

Another aspect of the military zone is the occurrence of dedications to

native gods by officers whilst hunting such as the dedications to Vinontonus,

presumed to have been set up in a shrine to the god situated on moorland a

few miles from the fort at Bowes, North Yorkshire.

TWMBibliography

Abbreviations

AE L’anee epigraphique

ANRW Aufsteig und Neidergang der Romischen Welt. Berlin

and New York

CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

RIB Collingwood, R. G., & Wright,

R. P. (1965) The Roman Inscriptions of Britain I. Oxford.

Aldhouse-Green, M. J. (2004) ‘Gallo-British Deities and their Shrines’ in Todd.,

M., (ed.) (2004), 193-219.

Allason-Jones, L. & McKay, B. (1985) Coventina’s

Well. Chester.

Birley, A. R. (1964) Life in

Roman Britain. London.

Birley, A. R. (1979) The people of Roman Britain. London.

Birley, E. (1986) ‘The Deities of Roman Britain’, in Hasse,

W. (ed.) Principat. Volume 18. Religion. ANRW, ii, 18, 3-112.

Birley, E., Brewis, P. & Charlton, J.,

(1934) ‘Report for 1933 of the North of England Excavation Committee’, Archaeologia Aeliana 4th series, xi, 176-205.

Breeze, D. J & Dobson, B. (2000) Hadrian’s

Wall. London.

Bruce, J. C., (1875) Lapidarium Septentrionale. Newcastle

upon Tyne.

Budge, J. A. W., (1907) An Account of the

Roman Antiquities preserved in the Museum at Chesters Northumberland. 2nd revised edition. London.

Collingwood, R. G. & Richmond, I. A. (1969) The

Archaeology of Roman Britain. 2nd rev. edn. London.

Green, M. J. (1983) The Gods of Roman Britain. Aylesbury.

Green, M. J. (1998) ‘God in Man’s Image: Thoughts on the Genesis and Affiliations

of some Romano-British Cult-imagery’ Britannia xxix, 17-30.

Haverfield, F. (1923) The Romanization of

Roman Britain. edited by G. Macdonald. Oxford.

Henig, M. (1984) Religion in Roman Britain. London.

Horsley, J., (1732) Britannia Romana.

Ross, A. (1967) Pagan Celtic Britain. Studies in

Iconography and Tradition. London.

Richmond, I, A., Hodgson, K. S. & St.

Joseph, K., (1938) ‘Report of the Cumberland Excavation Committee, directed

by F. G. Simpson. The Roman Fort at Bewcastle’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, new ser. xxxviii, 195-237.

Todd, M., (ed.) (2004) A Companion to Roman

Britain. Oxford.

Toynbee, J. M. C. (1962) Art in Roman Britain. London.

Wheeler, R. E. M. & Wheeler, T. V., (1932) Report

on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Site in Lydney

park, Gloucestershire. Rep. of the Res. Comm. of the Soc. of Antiq. of London, IX. Oxford.

Celtic religion was expressed as a belief in ‘the spirits of nature. Sea

and sky, mountains, rivers and trees…the sun, the source of heat and light,

and the moon, the measure of time…’ (Birley 1964, 136). All were thought to

be endowed with powerful spirits, as were certain animals and birds, seen as

having impressive attributes, and all deserving of worship by prayer and sacrifice.

Henig (1984) further emphasises this connection between natural features and

the divine world and claims that place-name evidence suggests that rivers in

particular received names long before the Celtic language was spoken, i.e.

the Thames may have been so named in the Bronze Age or earlier (ibid. 17). Further examples of the worship of these personified natural features include

Verbia, meaning ‘winding river’, attested on an altar at Ilkley, North Yorkshire

(RIB 635). This connection with water - the veneration of rivers and watery places,

especially bogs - is also attested in the numerous offerings of precious objects.

The

earth itself was also thought to be sacred. Shafts were sunk into the ground

in the Bronze Age and became more frequent in the Iron Age and Roman periods.

Evidence of sacrifices in these pits, along with the presence of great timbers,

suggests a symbolic sexual penetration of the earth thus constituting fertility

magic.

Celtic religion was expressed as a belief in ‘the spirits of nature. Sea

and sky, mountains, rivers and trees…the sun, the source of heat and light,

and the moon, the measure of time…’ (Birley 1964, 136). All were thought to

be endowed with powerful spirits, as were certain animals and birds, seen as

having impressive attributes, and all deserving of worship by prayer and sacrifice.

Henig (1984) further emphasises this connection between natural features and

the divine world and claims that place-name evidence suggests that rivers in

particular received names long before the Celtic language was spoken, i.e.

the Thames may have been so named in the Bronze Age or earlier (ibid. 17). Further examples of the worship of these personified natural features include

Verbia, meaning ‘winding river’, attested on an altar at Ilkley, North Yorkshire

(RIB 635). This connection with water - the veneration of rivers and watery places,

especially bogs - is also attested in the numerous offerings of precious objects.

The

earth itself was also thought to be sacred. Shafts were sunk into the ground

in the Bronze Age and became more frequent in the Iron Age and Roman periods.

Evidence of sacrifices in these pits, along with the presence of great timbers,

suggests a symbolic sexual penetration of the earth thus constituting fertility

magic.

Belatucadrus

Belatucadrus Cocidius

Cocidius