Origin of the vici

Relation

to traffic routes

Function of the

places

Typical building

structures

Changes in

construction methods

Religious cults

Summary

In the first centuries AD the Latin term vicus

was probably used in Moesian provinces both for the co called semi-urban settlement

(without the status of a city but with significant population, well-developed

industrial and/or commercial activity and /or other specific functions) and

the small farming community (rural village, such as Fântânele). In the regions

away from the Danube, where Greek was more popular than Latin, the respective

term was usually kome. Very little archaeological research has been carried

out in the late Iron Age settlements in Serbia and in northern Bulgaria. The

scant information about local population settlements in the last centuries

BC

hinders defining precisely the changes or continuity of the settlement pattern

after the establishment of the Roman rule. We do not know either if such

pre-Roman

settlements as Troesmis and Aegyssus in Dobrogea, mentioned by Ovid for AD

12 and 15, and other unidentified settlements near residences of Getic rulers,

continued to prosper under the Romans. Many vici in existence in the Roman period

have been attested only by epigraphy (see

map) and about twenty only surveyed or sampled archaeologically, mostly

by rescue digs (see map). The only village

of the Roman period which has been excavated systematically to a large extent

is a possible vicus around the villa at Pavlikeni

podpis in northern Bulgaria.

In the first centuries AD the Latin term vicus

was probably used in Moesian provinces both for the co called semi-urban settlement

(without the status of a city but with significant population, well-developed

industrial and/or commercial activity and /or other specific functions) and

the small farming community (rural village, such as Fântânele). In the regions

away from the Danube, where Greek was more popular than Latin, the respective

term was usually kome. Very little archaeological research has been carried

out in the late Iron Age settlements in Serbia and in northern Bulgaria. The

scant information about local population settlements in the last centuries

BC

hinders defining precisely the changes or continuity of the settlement pattern

after the establishment of the Roman rule. We do not know either if such

pre-Roman

settlements as Troesmis and Aegyssus in Dobrogea, mentioned by Ovid for AD

12 and 15, and other unidentified settlements near residences of Getic rulers,

continued to prosper under the Romans. Many vici in existence in the Roman period

have been attested only by epigraphy (see

map) and about twenty only surveyed or sampled archaeologically, mostly

by rescue digs (see map). The only village

of the Roman period which has been excavated systematically to a large extent

is a possible vicus around the villa at Pavlikeni

podpis in northern Bulgaria.

More

than a dozen sites in Dardania (central and southern part of Upper Moesia) and

barely a few in Lower Moesia, e.g. Straja in Dobrogea and probably also Prisovo

in northern Bulgaria, however, have yielded modest evidence of opposite trends

operating in the province at the time: important changes in the native, pre-Roman

settlement pattern in the former case, and the survival of a certain number

of the original villages in their original locations in the latter. The komai

on the Black Sea coast, occupied mostly by hellenized Thracian or Getic rural

communities, also remained unaffected by the Romans. Some of the native hill-forts

(refugium-like settlements) in Dardania (e.g. Lopate near statio Lamud) and

possibly also in the tribal territories (cf.

map), such as that of Celtic Scordisci (e.g. Singidunum), were abandoned

following the Roman conquest. The resettled population took upresidence probably

in new villages situated in the valleys or plains where it was easier to control.

More

than a dozen sites in Dardania (central and southern part of Upper Moesia) and

barely a few in Lower Moesia, e.g. Straja in Dobrogea and probably also Prisovo

in northern Bulgaria, however, have yielded modest evidence of opposite trends

operating in the province at the time: important changes in the native, pre-Roman

settlement pattern in the former case, and the survival of a certain number

of the original villages in their original locations in the latter. The komai

on the Black Sea coast, occupied mostly by hellenized Thracian or Getic rural

communities, also remained unaffected by the Romans. Some of the native hill-forts

(refugium-like settlements) in Dardania (e.g. Lopate near statio Lamud) and

possibly also in the tribal territories (cf.

map), such as that of Celtic Scordisci (e.g. Singidunum), were abandoned

following the Roman conquest. The resettled population took upresidence probably

in new villages situated in the valleys or plains where it was easier to control.

In Lower Moesia, the pre-Roman origin of at least some small rural communities

is indicated by the vici and komai bearing native, Thracian, Daco-Getic or

Celtic

names, attested epigraphically, however, not earlier than for the period of

integration in the 2nd to first half of the 3rd century AD. From the very beginning

of Roman military presence on the Lower Danube, extramural

settlements were established near military

sites: canabae around the legionary bases

as in Novae and vici next to auxiliary forts. Auxiliary townships, such

as Ravna (Timacum Minus), Sexaginta Prista

(Rousse), attested around AD 100, and the not much later Vicus Classicorum (Murighiol

in Dobrogea), attracted enterprising civilians, first from outside Moesia, then

also the natives, ready to provide for the soldiers’ needs. There is no information

on the evolution of auxiliary vici located on the Daco-Moesian provincial boundary

after the partial demilitarization of the Danube bank following the conquest

of Dacia (AD 106 - cf. map). Some of these

settlements certainly continued to exist, e.g. the semi-urban villages near

still operating auxiliary forts in the region of the Iron Gate in Karata? (Diana

Cataractarum), Donji Milanovac (Taliata) and Pontes opposite Drobeta (cf.

reconstruction). None of these vici has yet been excavated to such an extent

that we would be able to show its plan.

In Lower Moesia, the pre-Roman origin of at least some small rural communities

is indicated by the vici and komai bearing native, Thracian, Daco-Getic or

Celtic

names, attested epigraphically, however, not earlier than for the period of

integration in the 2nd to first half of the 3rd century AD. From the very beginning

of Roman military presence on the Lower Danube, extramural

settlements were established near military

sites: canabae around the legionary bases

as in Novae and vici next to auxiliary forts. Auxiliary townships, such

as Ravna (Timacum Minus), Sexaginta Prista

(Rousse), attested around AD 100, and the not much later Vicus Classicorum (Murighiol

in Dobrogea), attracted enterprising civilians, first from outside Moesia, then

also the natives, ready to provide for the soldiers’ needs. There is no information

on the evolution of auxiliary vici located on the Daco-Moesian provincial boundary

after the partial demilitarization of the Danube bank following the conquest

of Dacia (AD 106 - cf. map). Some of these

settlements certainly continued to exist, e.g. the semi-urban villages near

still operating auxiliary forts in the region of the Iron Gate in Karata? (Diana

Cataractarum), Donji Milanovac (Taliata) and Pontes opposite Drobeta (cf.

reconstruction). None of these vici has yet been excavated to such an extent

that we would be able to show its plan.

A

substantial number of the rural communities in Dobrogea (cf.

map), particularly those bearing Roman names, like Ulmetum and vicus Novus,

and occupied in the 2nd century by veterans and other Roman citizens, as well

as the Lai and Bessi resettled from Thrace, must have been established by the

Romans within the framework of a considered colonizing operation, probably shortly

after the conquest of Dacia (AD 106).

A

substantial number of the rural communities in Dobrogea (cf.

map), particularly those bearing Roman names, like Ulmetum and vicus Novus,

and occupied in the 2nd century by veterans and other Roman citizens, as well

as the Lai and Bessi resettled from Thrace, must have been established by the

Romans within the framework of a considered colonizing operation, probably shortly

after the conquest of Dacia (AD 106).  The

purpose of the colonization, as also of the earlier resettlement actions from

beyond the Danube, was undoubtedly to populate the hinterland of the limes and

provide a taxable source of income, and in the longer perspective, to create

a stable source of supplies and native recruits for troops stationing on the

Dobrogean section of the Danubian border, as well as an efficient maintenance

system for the newly-built road network. Finally,

there is an important group of rural villages in Dobrogea with toponyms formed

from personal names, e.g. vicus Quintionis. One is led to assume that these

settlements were established on private estates, taking their names after the

landowners. The 3rd century vicus at Pavlikeni in the territory of Nicopolis

ad Istrum owed its origin to a private villa (see

photo) with well developed, market oriented pottery production. There is

reason to suspect that some Moesian vici in existence in the Roman period and

depending upon their specialized functions as religious centres or spa-resorts

(e.g. Vrban and Vicus Casianum) originated from pre-Roman cult places stuated

sometimes near healing waters.

The

purpose of the colonization, as also of the earlier resettlement actions from

beyond the Danube, was undoubtedly to populate the hinterland of the limes and

provide a taxable source of income, and in the longer perspective, to create

a stable source of supplies and native recruits for troops stationing on the

Dobrogean section of the Danubian border, as well as an efficient maintenance

system for the newly-built road network. Finally,

there is an important group of rural villages in Dobrogea with toponyms formed

from personal names, e.g. vicus Quintionis. One is led to assume that these

settlements were established on private estates, taking their names after the

landowners. The 3rd century vicus at Pavlikeni in the territory of Nicopolis

ad Istrum owed its origin to a private villa (see

photo) with well developed, market oriented pottery production. There is

reason to suspect that some Moesian vici in existence in the Roman period and

depending upon their specialized functions as religious centres or spa-resorts

(e.g. Vrban and Vicus Casianum) originated from pre-Roman cult places stuated

sometimes near healing waters.

V. Dintchev (AIM-BAS), T. Sarnowski (IAUW)

V.H. Baumann, Aşezări rurale antice în zona gurilor Dunării. Contribuţii arheologice la cunoaştera habitatului rural (sec. I-IV p. Chr.), Tulcea 1995

V.H. Baumann, Noi săpături de salvare în aşezarea rurală antică de la Teliţa-Amza, jud. Tulcea, Peuce (NS) 1, 2003, 160 - 221

E. Čerškov, Rimljani na Kosovu i Metohiji, Beograd 1969

E. Condurachi, Beiträge zur Frage der ländlichen Bevölkerung in der römischen Dobrudscha, Corolla memoriae E. Swoboda dedicata, Graz-Köln, 95 -104

V.N. Dinčev, Polugradskite neukrepeni selišta prez rimskata, kâsnorimskata i rannovizantijskata epocha (I - načaloto na VII v.) v dnešnite bâlgarski zemi, Istorija 3-4, 1996, 99 -104

V.N. Dinčev, Selata v dnešnata bâlgarska teritorija prez rimskata epocha (I – kraja na III vek), Izvestija na Nacionalnija Istoričeski Muzej 11, 2000, 185 -218

S. Dušanić, Aspects of Roman Mining in Noricum, Pannonia, Dalmatia and Moesia Superior, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 55 -94

B. Gerov, Zemevladenieto v Rimska Trakija i Mizija (I-III v.), Sofia 1980

Z. Gočeva, Der thrakische Festungsbau und sein Fortleben im spätantiken Fortifikationssystem in Thrakien, in: J. Hermann et al. (eds), Griechenland-Byzanz-Europa. Ein Studienband, Berlin 1988, 97-107

M. Irimia, Nouvelles données concernant les habitats gétiques en Dobroudja pendant la seconde époque du fer, Pontica 13, 1980, 100 -118

M. Mirković, Einheimische Bevölkerung und römische Städte in der Provinz Obermösien, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 811 - 848

M. Mirković, Rimsko selo Bube kod Singidunuma, Starinar 39, 1988, 99 -104

A.G. Poulter, Rural Communities (Vici and komai) and Their Role in the Organization of the Limes of Moesia Inferior, in: Roman Frontier Studies 1979 (= British Archaeological Reports. Intern. Series 71 III), Oxford 1980, 729 -743

A.G. Poulter, Cataclysm on the Lower Danube: The Destruction of a Complex Roman Landscape, in: N. Christie (ed.), Landscapes of Change. Rural Evolutions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Aldorshot 2004

A. Suceveanu, Viaţa economică în Dobrogea romană secolele I - III e.n., Bucureşti 1977

A. Suceveanu, Fântânele. Contribuţii la studiul vieţii rurale în Dobrogea romană, Bucureşti 1998

A. Suceveanu, Al. Zahariade, Un nouveau vicus sur le territoire de la Dobroudja romaine, Dacia 30, 1986, 109-120

V. Velkov, Kâm vâprosa za agrarnite otnošenija v Mizija prez II v. na n.e., Archeologija 4, 1962, 31-35

V. Velkov, Die Stadt und das Dorf in Südosteuropa, Actes du IIe Congrès Intern. des Études du Sud-Est Européen, Athènes 1970, 147-166

V. Velkov, Dobrudža v perioda na rimskoto vladičestvo (I-III v.), in: A. Fol,

S. Dimitrov (eds), Istorija na Dobrudža, I, Sofia 1984, 124-155

The growth and pattern of semi-urban and rural settlement in both Moesian provinces in the second century AD is clearly associated with the establishment of the Roman road network and the process of its extending. This concerns especially the Danubian Plain (Lower Moesia after AD 86), which was underpopulated in the first century. The creation of the first military lines of communication (viae militares) was accompanied, no later than in Nero’s reign (AD 54-68), by the establishment of numerous road and posting stations (mansiones) with all necessary buildings such as tabernae and praetoria mentioned in a contemporary inscription from Thrace.To believe later sources, such as the fourth-century Tabula Peutingeriana, there were as many as 10 posting stations operating on just one, hardly the longest road from Oescus to Philippopolis in Thrace. These stations (e.g. Storgosia, Melta, Sostra) have been located in the field and in the vicinity of each there is very fragmentary evidence of settlement; future research will presumably qualify this settlements as semi-urban villages (cf. map). On the important limes road along the Danube with its difficult section in the region of Iron Gate (Djerdap) the posting stations were probably located in the vici near still functioning or evacuated after the conquest of Dacia auxiliary forts.

the

numerous rural villages in Dobrogea (cf. map)

owed their development largely to their location near the Roman roads, although

the situation had also its weaknesses. An inscription, now in the Museum of

Constan?, refers to some burdensome duties imposed on the inhabitants of Chora

Dagei and Laikos Pyrgos in connection with the villages’ location near a public

road (via publica). The duties, which were required of the inhabitants several

times in a year by the liturgiai and angareiai systems, were connected with

supplying the public post (cursus publicus). Abuses by the provincial administration

with regard to villages lying on the roads, and especially on the road crossings,

could have been prevented sometimes by the beneficiarii consularis, soldiers

detached from the legions for policing the roads. Their stations have been confirmed

epigraphically in some semi-urban (Sočanica - cf.

plan, Pavlikeni - cf. plan, Storgosia)

as well as rural villages (Râmnicu de Jos - Vicus V... and Mihai Bravu - Vicus

Bad...).

the

numerous rural villages in Dobrogea (cf. map)

owed their development largely to their location near the Roman roads, although

the situation had also its weaknesses. An inscription, now in the Museum of

Constan?, refers to some burdensome duties imposed on the inhabitants of Chora

Dagei and Laikos Pyrgos in connection with the villages’ location near a public

road (via publica). The duties, which were required of the inhabitants several

times in a year by the liturgiai and angareiai systems, were connected with

supplying the public post (cursus publicus). Abuses by the provincial administration

with regard to villages lying on the roads, and especially on the road crossings,

could have been prevented sometimes by the beneficiarii consularis, soldiers

detached from the legions for policing the roads. Their stations have been confirmed

epigraphically in some semi-urban (Sočanica - cf.

plan, Pavlikeni - cf. plan, Storgosia)

as well as rural villages (Râmnicu de Jos - Vicus V... and Mihai Bravu - Vicus

Bad...).

E. Čerškov, Rimljani na Kosovu i Metohiji, Beograd 1969

V.N. Dinčev, Polugradskite neukrepeni selišta prez rimskata, kâsnorimskata i rannovizantijskata epocha (I - načaloto na VII v.) v dnešnite bâlgarski zemi, Istorija 3-4, 1996, 99-104

V.N. Dinčev, Selata v dnešnata bâlgarska teritorija prez rimskata epocha (I – kraja na III vek), Izvestija na Nacionalnija Istoričeski Muzej 11, 2000, 185 -218

K. Dočev, Stari rimski pâtišta v Centralna Dolna Mizija (II-IV v. sl. Chr.), Sbornik Rjahovec. Veliko Târnovo-G. Orjahovica 1994, 61 -76

B. Gerov, Zemevladenieto v Rimska Trakija i Mizija (I - III v.), Sofia 1980

M. Madžarov, Rimskijat pât Eskus-Filipopol. Pâtni stancii i selišta, Plovdiv 2004

M. Mirković, Einheimische Bevölkerung und römische Städte in der Provinz Obermösien, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 811-848

M. Mirković, Vom obermösischen Limes nach dem Süden: Via Nova von Viminacium nach Dardanien, in: Roman Frontier Studies 1979 (= British Archaeological Reports. Intern. Series 71 III), Oxford 1980, 745-755

A.G. Poulter, Rural Communities (Vici and komai) and Their Role in the Organization of the Limes of Moesia Inferior, in: Roman Frontier Studies 1979 (= British Archaeological Reports. Intern. Series 71 III), Oxford 1980, 729 -743

A. Suceveanu, Viaţa economică în Dobrogea romană secolele I-III e.n., Bucureşti 1977

Y. Todorov, Le grandi strade romane in Bulgaria, Roma 1937

S. Torbatov, The Roman Road Durostorum – Marcianopolis, Archaeologia Bulgarica 4, 2000, 59-72

M. Vasić, G. Milošević, Mansio Idimum. Roman Post Station near Medveđa, Belgrade 2000

V. Velkov, Dobrudža v perioda na rimskoto vladičestvo (I-III v.), in: A. Fol, S. Dimitrov (eds), Istorija na Dobrudža, I, Sofia 1984, 124-155

Considering that few Moesian vici have so far been "sampled" either

by field walking or rescue digs (cf.

map), and none has yet been excavated in full (cf. Pavlikeni as one possible

exception - see plan), we are forced to

draw conclusions on their function and role in the life of the province mainly

on the grounds of analyses of the following data: location and geographical

distribution - see map; social,

ethnic and professional make-up of the population ; practiced religious

cults; toponymy; evidence of various agricultural and industrial activities;

finds of tools and the presence of structures of special purpose.

Most Moesian vici were relatively small

rural communities, which regardless of origin were usually dependent on the agricultural

exploitation of their territories (terrae vici). They usually operated a mixed

agricultural and pastoral economy (e.g. Fântânele in Dobrogea - cf.

plan). While in the fertile farming lowlands defining for the economy of

villages was grain production, in the semi-mountainous and mountainous regions

cattle breeding played a very significant role. Other agricultural activities,

such as cultivation of vines and fruit trees or growing vegetables have left

less archaeological traces. Traditional occupations of farming, often enough

with grain cultivation on a medium scale, are signaled not only by finds of

agricultural implements; some villages had small substantial granaries (Mihai

Bravu, Kurt Baiîr), others have yielded

religious dedications to "agricultural" deities (Silvanus Sator,

Ceres, Liber Pater), and the gravestone of

one of the inhabitants of Vicus Ulmetum in Dobrogea depicts the ploughing

of fields and the tending of a flock of sheep.

The inhabitants of at least some of the vici on the Danube

or Black Sea coast understandably must have been involved in fishing, shipping

and commerce; testifying to this, for example, are the name of a settlement

in

Dobrogea (Vicus Classicorum - cf. photo),

a ship representation from Vicus Celeris

and the presence of a sailing corporation (nautae universi Danuvii) in another

village (Axiopolis). The Histrian custom documents allow to assume that the

villagers

at the mouth of the Danube were deriving some income from production and trading

salted fish and wood, probably with neighbouring villages and through Histria

also with more distant cities on the Black Sea littoral. Meaningful in this

respect are also two religious dedications from a vicus near Durostorum: one

was to Mercury,

the Roman deity of trade, and the other to the Winds (Flattoribus Ventis) and

the Good Gust of Wind (Bono Flanti). It is likely that some of these unexcavated

villages were semi-urban in character and occasionally fully deserved to be

styled as small towns or townships.

The inhabitants of at least some of the vici on the Danube

or Black Sea coast understandably must have been involved in fishing, shipping

and commerce; testifying to this, for example, are the name of a settlement

in

Dobrogea (Vicus Classicorum - cf. photo),

a ship representation from Vicus Celeris

and the presence of a sailing corporation (nautae universi Danuvii) in another

village (Axiopolis). The Histrian custom documents allow to assume that the

villagers

at the mouth of the Danube were deriving some income from production and trading

salted fish and wood, probably with neighbouring villages and through Histria

also with more distant cities on the Black Sea littoral. Meaningful in this

respect are also two religious dedications from a vicus near Durostorum: one

was to Mercury,

the Roman deity of trade, and the other to the Winds (Flattoribus Ventis) and

the Good Gust of Wind (Bono Flanti). It is likely that some of these unexcavated

villages were semi-urban in character and occasionally fully deserved to be

styled as small towns or townships.

The inhabitants of a few rural villages (e.g. Kamen - see

plan), Credin?, Niculi?l, Vicus Ulmetum, Gura Canliei) engaged in industrial

activity, usually conducted on a small scale, course pottery and sun-dried bricks

production, ore smelting, iron, copper and bone working, blacksmithing; weaving

was also an important domestic industry. An additional source of income was probably

for the villagers from some Moesian rural vici work at burning limestone and in

stonepits situated in the countryside near such settlements as for instance Hotnica

in the territory of Nicopolis ad Istrum, ?rnavoda, Dobromir and Dervent in Dobrogea.

A very important group of Moesian settlements was composed

of the vici situated in the Upper Moesian mining districts - see

map (e.g. vici metalli at Socanica, Jezero, Stojnik) and the vici functioning

in Lower Moesia as production and/or market centres (e.g. Butovo-Emporium Piretensium,

Pavlikeni, Hotnica). The latter ones, lying in the territory of Nicopolis ad Istrum,

played an important role as places for large local and regional pottery industry,

including fine, high quality table ware. The pottery industry at Pavlikeni, dependent

first (2nd century AD) upon a private villa (see

photo) and then (3rd century AD) upon a later vicus (see

plan) was operated not only by the inhabitants, but presumably also by slaves.

|

|||

Kamen |

Pavlikeni private villa |

The vessels produced in Butovo are to be found not only on civilian and military sites in Lower Moesia but also in Lower Dacia and in the Crimea beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire. To judge by the better investigated examples, such as Socanica in Dardania (cf. plan) and Pavlikeni in Lower Moesia (see plan), most vici which can be qualified as mining, industry or market settlements had a physical appearance of semi-urban settlements with workshops, pottery kilns, buildings accommodating the workers or for the storage of goods for sale and a variety of additional amenities, such as e.g. basilical halls and other public buildings. With due caution the same can be said probably about the vici by road stations (e.g. Storgosia, Graničak) even if at the moment no plans of such settlements from the period of Principate are available. The Serbian archaeologists suppose that at Metvedja on the road Viminacium – Horreum Margi (cf. map) a vicus with shops, inns and private workshops servicing the travellors existed already before the erection of the well studied buildings of the official posting station (Mansio Idimum), dated to the 4th century AD. In keeping with a practice known from other provinces, not only the inhabitants of the rural vici but also the occupants of the semi-urban settlements by road stations had to fill duties connected with road maintenance and the operation of the public post (cursus publicus). Epigraphic documentation of this phenomenon in the mid second century AD in Lower Moesia refers to the Dobrogean villages of Chora Dagei and Laikos Pyrgos.

|

|

|

Very little can be said about the Moesian vici situated near hot-water springs, sometimes developed into spa-resorts (e.g. Vrban in Dardania) and about the settlements near native religious sites (e.g. Vicus Casianum in Dobrogea). The vicus Storgosia formed near the official station on the road Oescus – Philippopolis performed its function probably also as the religious centre of the territorium Dianensium. Because of unsufficient state of archaeological research (no plans available) we can only guess that like in other frontier provinces of the Roman Empire these settlements that derived considerable income from healing properties of the springs or as regional centres of pilgrimage showed the characteristics that distinguished them from usual rural vici; it has been suggested that they sometimes merited the description of "small towns" or "townships".

|

||

While

discussing the function of the Moesian vici one has to take into account

an important role played especially in the period of occupation

and early in the period of integration by the extramural vici near existing

or

evacuated auxiliary forts (ex. Timacum Minus - cf. map,

Taliata, Sexaginta Prista) or vici situated about 2 km = 1 leuga (cf.

plan) from legionary fortresses (ex. Ostrite

Mogili municipalized as Municipium Novensium; Ostrov municipalized as Municipium

Aurelium Durostorum). Their location with regard to military sites determined

their primary function, e.g. commerce, industry, services, crafts. An incomplete

state of current archaeological research (no stratified plans available)

does

not allow to distinguish the early phases of settlements from the later

ones after the garrison’s departure, as occurred in some of the Upper Moesian

and western

Lower Moesian auxiliary forts or after the grant of municipal autonomy

for

the vici at Ostrite Mogili and Ostrov. Starting from the second half of

the first

century AD, some of the vici existing near former (possibly Pincum and

Tricornium) or still functioning forts (cf. map) occupied

by auxiliary troops (Dimum ?, Timacum Minus ?), likely took

over the function of centres (capita civitatium - see

map) of civilian territorial organization as tribal

capitals.

The geographical distribution of rural vici attested epigraphically,

demonstrating a concentration in Dobrogea, suggests that contrary to the

other parts of the two Moesian provinces (see map),

which presumably enjoyed a greater share of big land estates left in state,

imperial

and private hands (e.g. between Ratiaria and Oescus and to the east of

Yantra river), the Dobrogean rural villages played an important role both

in providing

the Greek towns on the Black Sea coast with agricultural products and in

the system

of supplying the troops stationed along the Lower Danubian limes.

|

|

|

|

| Vici near forts | Timacum Minus | Capita civitatium | Rural vici |

E. Čerškov, Rimljani na Kosovu i Metohiji, Beograd 1969

E. Condurachi, Beiträge zur Frage der ländlichen Bevölkerung in der römischen Dobrudscha, Corolla memoriae E. Swoboda dedicata, Graz-Köln, 95 -104

V.N. Dinčev, Polugradskite neukrepeni selišta prez rimskata, kâsnorimskata i rannovizantijskata epocha (I- načaloto na VII v.) v dnešnite bâlgarski zemi, Istorija 3-4, 1996, 99 -104

V.N. Dinčev, Selata v dnešnata bâlgarska teritorija prez rimskata epocha (I – kraja na III vek), Izvestija na Nacionalnija Istoričeski Muzej 11, 2000, 185 - 218

S. Dušanić, Aspects of Roman Mining in Noricum, Pannonia, Dalmatia and Moesia Superior, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 55 - 94

B. Gerov, Zemevladenieto v Rimska Trakija i Mizija (I-III v.), Sofia 1980

M. Madžarov, Rimskijat pât Eskus-Filipopol. Pâtni stancii i selišta, Plovdiv 2004

M. Mirković, Einheimische Bevölkerung und römische Städte in der Provinz Obermösien, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 811 - 848

A.G. Poulter, Rural Communities (Vici and komai) and Their Role in the Organization of the Limes of Moesia Inferior, Roman Frontier Studies 1979 (= British Archaeological Reports. Intern. Series 71 III), Oxford 1980, 729 -743

A.G. Poulter, Cataclysm on the Lower Danube: The Destruction of a Complex Roman Landscape, in: N. Christie (ed.), Landscapes of Change. Rural Evolutions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Aldorshot 2004

A. Suceveanu, Viaţa economică în Dobrogea romană secolele I-III e.n., Bucureşti 1977

A. Suceveanu, Fântânele. Contribuţii la studiul vieţii rurale în Dobrogea romană Bucureşti 1998

M. Vasić, G. Milošević, Mansio Idimum. Roman Post Station near Medveđa, Belgrade 2000

V. Velkov, Die Stadt und das Dorf in Südosteuropa, Actes du IIe Congrès Intern. des Études du Sud-Est Européen, Athènes 1970, 147-166

Our knowledge of typical building structures from vici (cf.

map) of different origins and function in Upper and Lower Moesia is largely

imperfect and it can hardly be otherwise considering how relatively few regular

excavations (cf. map) have been carried

out. Indeed, most of the work has been of a salvage nature.

To judge by extensive spread of surface pottery and building

debris some of the Moesian semi-urban settlements covered an area of over 10

ha. The rural villages were not much smaller; in the full extent they could

have measured often about or even over 10 ha. In the fertile agricultural regions,

such as for instance in the hinterland of the limes (cf.

map) to the south of Novae and east of the Yantra river the latest archaeological

survey shows a relatively dense settlement system; rural villages and villas

were spaced there from 2 to 5 km from each other.

|

|

|

With the exception of the semi-urban vicus at Socanica (cf. plan) in Dardania with regular spacing of streets and buildings the current state of research of the Moesian vici does not show any sign of planning in the layout of streets. In the auxiliary vicus at Ravna-Timacum Minus where such amenities as bath buildings were shared between fort and settlement private dwellings and other buildings encircled the fort on three sides. The location of cemetery at some distance from the fort seems to suggest that it was planned like in in Britain or German provinces far enough to create necessary space for the construction of the vicus. If our reconstruction of the layout of streets in Ostrite Mogili (see plan) is right, it probably appeared only in the later period when in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD the vicus received municipal status.

|

|

| Socanica | Ostrite Mogili |

The only investigated to some extent rural vici in the Moesian

provinces (Fântânele and Kamen) show two different layout patterns: roadside

villages (Fântânele with farmsteads situated along both sides of a small river

- see plan) and settlements with widely spaced courtyard

farmhouses of peasant renters situated among parcels of arable land (Kamen -

see plan). Drawing an analogy from the

adjacent territories of the Roman province Thracia it can be speculated that

the unifying components of such vici were their common tumulus cemeteries and,

possibly, isolated sanctuaries. The sanctuaries,

when there were any (ex. Vicus Casianum), were on the periphery of the villages

or at a certain distance from them. Such seem to be the vicus-sites at Goljama

Brestnica (Longinopara ?), Prisovo, Gorsko Ablanovo, Niculi?l, Teli?-Amza, Sarichioi

and Sveti Nikola (no plans available).

|

|

|

| Fântânele | Kamen |

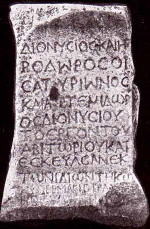

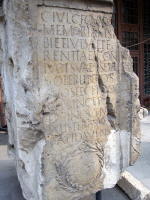

Valuable information about various buildings in the

Moesian vici has been provided by finds of inscribed stones. Public buildings

erected in the settlements were mentioned in a few Latin and Greek

building

inscriptions, originating from the Lower and Upper Moesian vici. Temples

of Jupiter Best and Greatest, Jupiter and Hercules, Jupiter Dolichenus,

Diana,

Mars, Antinous, Terra Mater, Mithras are attested epigraphically by building

inscriptions from semi-urban villages at Ravna (Timacum Minus), Socanica,

Lopate,

Guberevac, Sopot and Rudnik in Upper Moesia, and from rural or possible

rural settlements at Bjala Slatina, Dragoevo, Ko?ov, Valea Teilor

and Urluia

in Lower Moesia. One of the temples attested epigraphically (see

map) was excavated (the temple to Antinous

at Socanica). The presence of a temple or chapel at a given location could

be deduced occasionally from a concentration of religious

dedications devoted to a single deity found at one site (ex. dedications

to oriental deities Mithras and Jupiter Dolichenus in Ravna – Timacum

Minus) or the mention in an inscription of a religious association (e.g.

in Vicus Clementianensis,

Vicus Ulmetum, Neat?nea and in Butovo).

|

|

|

| Villages

with public buildings attested epigraphically |

|||

| Semi-urban

villages in mining districts |

Semi-urban

villages by road stations |

Rural villages | Possible rural villages |

| TEMPLES | |||

| Guberevac Sočanica Sopot Rudnik |

Lopate Kuršumlijska Banja |

Gromšin Valea Teilor Urluia |

Bjala

Slatina Dragoevo Košov |

| BATHS | |||

| Vicus

Petra |

Rousse Karataš |

||

| OTHER BUILDINGS | |||

| Caranasuf (Abitorion), Vicus Quintionis (Auditorium) |

|||

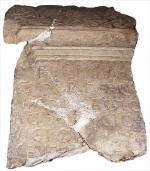

There is epigraphical confirmation of three public structures in three of the rural vici from the territory of modern-day Dobrogea: an auditorium or assembly hall in the vicus Quintionis in the countryside (chora) of Histria, which served the needs of not only the elected officials (magistri vici), but probably also other representatives of the inhabitants (veterani et cives Romani et Bessi consistentes) of a settlement clearly boasting quasi- or premunicipal organization; a balineum or bath in the vicus Petra (see inscription) in central northern Dobrogea, erected by the vicani Petrenses "for the health of the body" (causa salutis corporis); an abitorion at Caranasuf near Histria, a structure of unknown function, believed by some to be an outdoor toilet facility. According to an inscription from Sinoe-Casapchioi (vicus Quintionis), the auditorium there was rebuilt in the reign of Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161), which could mean that it had been in operation at an earlier date already.

|

|

|

| Dobrogea |

None of the buildings mentioned in the

second and third century inscriptions from Dobrogea has been excavated

so far. We are entitled to assume,

however,

that the village assembly halls, wherever they actually existed, could

not have been much different from Building D in the Romano-Getic settlement

of Teli?-Amza in northern Dobrogea. This structure, which covered an

area

of over 130 m2, consisted of two small rooms located symmetrically on

either side of the entrance, and a big rectangular room in the back

(7.15 by 9.70

m), divided symmetrically into three aisles by two rows of three supports

(columns ?). The discoverers presumed the existence of columns in the

entrance,

which measured 3.20 m in width. The pavement in this building was of

stone.

As in other frontier provinces in Europe, so on the Lower

Danube, baths (thermae) in semi-urban vici lying near the auxiliary forts

were what one might call a canonical building structure. Inscriptions

found

at Rousse in Bulgaria and at Karata? in Serbia speak of such

buildings in Sexaginta Prista and Diana Cataractarum. Two bath-houses

were excavated in Ravna (Timacum Minus - cf. plan)

and one in Donji Milanovac (Taliata). There is no way to estimate, however,

to what

extent also the rural landscape of Moesian vici was dotted with similar

public baths, such as already mentioned balineum in vicus Petra. Perhaps

clay water-pipe systems, such as those

found at Pavlikeni, also supplied modest village balinea with water.

As in other frontier provinces in Europe, so on the Lower

Danube, baths (thermae) in semi-urban vici lying near the auxiliary forts

were what one might call a canonical building structure. Inscriptions

found

at Rousse in Bulgaria and at Karata? in Serbia speak of such

buildings in Sexaginta Prista and Diana Cataractarum. Two bath-houses

were excavated in Ravna (Timacum Minus - cf. plan)

and one in Donji Milanovac (Taliata). There is no way to estimate, however,

to what

extent also the rural landscape of Moesian vici was dotted with similar

public baths, such as already mentioned balineum in vicus Petra. Perhaps

clay water-pipe systems, such as those

found at Pavlikeni, also supplied modest village balinea with water.

The presently known homesteads from the Moesian rural

villages can be divided into a number of types. The most modest of the

huts are similar to the late Iron Age Grubenh?ser (sunken-floored huts).

These

single-room, usually oval, but occasionally rectangular and trapezoidal

habitations found in a few Dobrogean vici, had a surface area ranging

from

9 to 20 m2.

In the first and early second century AD settlement at Teli?-Amza, the

huts formed small groups of two or three, set some 50 m apart as a rule

(no general

plan available). They were sunk a few dozen centimeters into the ground.

A massive post in the center suggests a conical roof supported on low

walls;

without a central post, the hut appeared more like an ordinary shelter.

Interior furnishings (features and installations) included storage pits,

earth platforms (for sleeping ?) and fireplaces. The latter were occasionally

built outside the huts.

Considering mentions of Troglodytae (Troglodytai),

whom Strabo, Pliny and Ptolemy all reported among the peoples inhabiting

eastern Moesia (cf. map)

in the first century AD, one is led to believe, based also on the etymology

of the name, that at least some of the local population lived seasonally

in caves. This is an archaeologically confirmed fact for the pre-Roman

period.

It is possible, however, that the name referred to people who were still

actually living in huts sunk in the loess at the beginning of the Roman

period.

Considering mentions of Troglodytae (Troglodytai),

whom Strabo, Pliny and Ptolemy all reported among the peoples inhabiting

eastern Moesia (cf. map)

in the first century AD, one is led to believe, based also on the etymology

of the name, that at least some of the local population lived seasonally

in caves. This is an archaeologically confirmed fact for the pre-Roman

period.

It is possible, however, that the name referred to people who were still

actually living in huts sunk in the loess at the beginning of the Roman

period.

In the second and third century AD, the inhabitants of

rural settlements in Dobrogea and on the Danubian Plain generally lived

in farmhouses. The evolution of this form is well exemplified by investigations

carried out in the settlement of Fântânele(see map)

situated in the countryside of the Greek colony of Histria.

Prior

to being destroyed at the end of the second century AD, Dwelling α

(see plan)

was a rectangular building, consisting of a courtyard (a) and two small

rooms (b, c). The courtyard could have been taken up in part by a roofed

portico supported on stone columns; eight small limestone column bases

were

found, unfortunately not in situ, along with two shaft fragments and

one capital. A structure found near the southeastern corner, of which

merely

two short sections of walls survive, must have served as a sort of outbuilding.

The alleged presence of a portico in the farmhouse of the first phase

(c.

AD 150) suggested to the discoverer the potential influence of Hellenistic

domestic architecture. In phase II (see

plan), the building developed into a block measuring 30 by 11.75 m.

It then incorporated four clearly distinct parts: a residential quarter

supplemented by a large cooking area and dining room (g), and a domestic

part consisting primarily of a semi-open stockyard (h) and small storeroom

? (i).

Prior

to being destroyed at the end of the second century AD, Dwelling α

(see plan)

was a rectangular building, consisting of a courtyard (a) and two small

rooms (b, c). The courtyard could have been taken up in part by a roofed

portico supported on stone columns; eight small limestone column bases

were

found, unfortunately not in situ, along with two shaft fragments and

one capital. A structure found near the southeastern corner, of which

merely

two short sections of walls survive, must have served as a sort of outbuilding.

The alleged presence of a portico in the farmhouse of the first phase

(c.

AD 150) suggested to the discoverer the potential influence of Hellenistic

domestic architecture. In phase II (see

plan), the building developed into a block measuring 30 by 11.75 m.

It then incorporated four clearly distinct parts: a residential quarter

supplemented by a large cooking area and dining room (g), and a domestic

part consisting primarily of a semi-open stockyard (h) and small storeroom

? (i).

At

approximately the same time, the closely set buildings of a settlement discovered

in Kurt Baiîr near the modern

locality of Slava Cercheză in central northern Dobrogea were block-like

(or single-body)

rectangular structures (see

plan),

measuring respectively 85 and 147 m2 in area. Living and domestic

quarters, ranging in number from one to three, in the back part of

the complex,

were

preceded by a kind of long gallery in front. A grand entrance with

two columns was featured in one of the buildings. With time, a small

room

(e) was built,

joining the two structures into one complex, which by then also included

a separate outbuilding in the form of a rectangular stone-paved granary.

At

approximately the same time, the closely set buildings of a settlement discovered

in Kurt Baiîr near the modern

locality of Slava Cercheză in central northern Dobrogea were block-like

(or single-body)

rectangular structures (see

plan),

measuring respectively 85 and 147 m2 in area. Living and domestic

quarters, ranging in number from one to three, in the back part of

the complex,

were

preceded by a kind of long gallery in front. A grand entrance with

two columns was featured in one of the buildings. With time, a small

room

(e) was built,

joining the two structures into one complex, which by then also included

a separate outbuilding in the form of a rectangular stone-paved granary.

In

the Danubian Plain, a plan similar to the one described above was

demonstrated by some homesteads in the settlement that

arose around the villa in Pavlikeni (see

plan),

which specialized in ceramic vessel production. The same plan was

also to

be discerned in the remains explored in the settlement at Kamen (see

plan), this and the previous site being both situated in the rural hinterland

of Nicopolis ad Istrum.

|

|

|

|

| Pavlikeni | Kamen | Prisovo |

Most of the buildings combining living and

domestic functions in one enclosure, which are known from present-day

northern Bulgaria, resemble the villa-farms with big open courtyards

surrounded by

rows of rectangular rooms developing one after the other. A typical

example is a building from Prisovo (see plan),

a settlement located south of Nicopolis ad Istrum. The structure

(see

plan) occupied an area of 22.5 by 24 m and incorporated a courtyard

with alleged portico on the northern side, storeroom (4) and what

were evidently living quarters (2, 3, 6), as well as domestic units

(1, 7,

9, 10); it also

contained a heated room (corn dryer ?) featuring a hypocaust system

(5). A similar installation was also found at the biggest villa-like

building

discovered at V?bovska Reka in Pavlikeni.

In the semi-urban settlement at Stojnik in the mining district of

Kosmaj in Upper Moesia some of the houses were also equipped with

hypocaust

heeting and decorated with frescos (no plans available).

L. Kovalevska, T. Sarnowski (IAUW), V. Dintchev (IAM-BAS)

V.H. Baumann, Aşezări rurale antice în zona gurilor Dunării. Contribuţii arheologice la cunoaştera habitatului rural (sec. I-IV p. Chr.), Tulcea 1995

V.H. Baumann, Noi săpături de salvare în aşezarea rurală antică de la Teliţa-Amza, jud. Tulcea, Peuce 1 (14), 2003, 155 - 181

I. Cârov, Edin rimski vikus kraj selo Kamen, Izvestija na Istoričeski Muzej – V. Târnovo 12, 1997, 124 -133

E. Čerškov, Rimljani na Kosovu i Metohiji, Beograd 1969

E. Čerškov, Municipium DD kod Sočanice, Beograd 1970

S. Conrad, D. Stančev, Archaeological Survey on the Lower Danube between Novae and Sexaginta Prista, in: Limes XVIII (= British Archaeological Reports. Intern. Series 1084 II), Oxford 2002, 673-684

V.N. Dinčev, Selata v dnešnata bâlgarska teritorija prez rimskata epocha (I – kraja na III vek), Izvestija na Nacionalnija Istoričeski Muzej 11, 2000, 185 - 218

A. i C. Opaiţ, T. Bănică, Das ländliche Territorium der Stadt Ibida (2.-7. Jh.) und einige Betrachtungen zum Leben auf dem Land an der unteren Donau, Die Schwarzmeerküste in der Spätantike und im frühen Mittelalter, Wien 1992, 103 -112

P. Petrović, Inscriptions de la Mésie Supérieure. III 2. Timacum Minus et la Vallée du Timok, Beograd 1995

A.G. Poulter, Cataclysm on the Lower Danube: The Destruction of a Complex Roman Landscape, in: N. Christie (ed.), Landscapes of Change. Rural Evolutions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Aldorshot 2004

A. Suceveanu, Fântânele. Contribuţii la studiul vieţii rurale în Dobrogea romană Bucureşti 1998

B. Sultov, Edna villa rustica kraj s. Prisovo V. Târnovski

okrâg, Izvestija na Okrâžnija Muzej V. Târnovo, 2, 1964, 49-64

The only 1st and early 2nd century AD building structures from the Moesian

vici, of which we have knowledge that is more substantial, are the huts

with sunken floors (Grubenh?ser) in the settlement at Teli?-Amza in

Dobrogea. Made of impermanent materials, namely wood, branches and clay,

they were constructed in a manner that did not differ substantially

from

the later Iron Age habitations of the population living both to the north

and south of the lower course of Danube. The huts were of two kinds:

with

a central post and without, but in all cases the floors were sunken up

to a few dozen centimeters below ground level. The post was made of

a tree

trunk, while smaller stakes around the circumference formed the framework

for the wattle-and-daub walls. Stake-holes in huts without walls testify

to a conical roof construction made of thatch, reed and branches, and sealed

with daub. A similar roof but supported on a central post

covered huts with low walls.

|

|

|

|

| Fântânele | Prisovo | Kamen | Pavlikeni |

In the second and early third centuries AD, the sites

of Teli?-Amza and Prisovo (which had probably started out in the later Iron

Age as native hamlet-like settlements with modest huts) developed into well-organized

villages with at least a few romanized farmhouses each. The settlements

at Fântânele (see plan), Prisovo (see

plan)and Kamen (see plan) must

have become vici of this sort, too, around AD 200. Their appearance must

have been very much like that of second-century settlements, which grew

on villa estates, as in Pavlikeni (see

plan), for example. One of the characteristic elements of changing construction

was, among others, the increasingly frequent use of stone in the pavements

of some buildings and outbuildings, as well as in wall foundations. Another

newly introduced element were bricks and roof tiles fired in relatively

high temperatures, used alongside mud brick. Thus, stone appears as

a building material even in the principally wooden sunken-floored huts of

the first and early second century. At Sarichioi in northeastern Dobrogea,

the roof supports in the entrances to the sunken-floored huts were made

of stone.

In the end of the second and in the early third century,

and in Dobrogea even around the middle of the second century, the farmhouse-like

homesteads (cf. reconstruction)

in the Moesian rural vici were erected on stone foundations, typically raised

some 20 to 30 cm above ground level and forming a kind of base straight

on the ground. Broken sandstone, limestone and argillaceous slate from local

outcrops was almost invariably earth-bonded. Possibly under the influence

of villa architecture, which had already become heavily romanized at an

earlier date, in some of the vici the bearing walls of the bigger homesteads

(perhaps high-status dwellings) had stone foundations sunk up to 50 cm into

the ground (e.g. Prisovo - see plan

and reconstruction). The use of lime mortar was noted in a few cases,

as well as the presence of small quantities of lime in the bonding material

(vicus Petra in Dobrogea, Kamen and Prisovo on the Danubian Plain); these

were prepared according to requirements, as evidenced by a square pit containing

more than 4 m3 of lime, discovered 9 m from the farmhouse in Prisovo .

The

thickness of bearing walls was 0.50-0.65 m and 0.80 m (exceptionally in

Kamen), while partition walls were about 0.45 m thick. Low foundations

or substructures supported walls erected of either mud brick or wattle-and-daub,

or tamped loess or clay in boarding formwork. The substructure of one of

the partition walls in Prisovo included rectangular kiln-baked bricks with

holes a few centimeters deep used to mount the vertical elements of a wooden

wall framework. Walls constructed in this manner were capable of supporting

not only a mud-coated roof of thatch, straw or branches, but also the much

heavier roofs made of fired tiles.

In the end of the second and in the early third century,

and in Dobrogea even around the middle of the second century, the farmhouse-like

homesteads (cf. reconstruction)

in the Moesian rural vici were erected on stone foundations, typically raised

some 20 to 30 cm above ground level and forming a kind of base straight

on the ground. Broken sandstone, limestone and argillaceous slate from local

outcrops was almost invariably earth-bonded. Possibly under the influence

of villa architecture, which had already become heavily romanized at an

earlier date, in some of the vici the bearing walls of the bigger homesteads

(perhaps high-status dwellings) had stone foundations sunk up to 50 cm into

the ground (e.g. Prisovo - see plan

and reconstruction). The use of lime mortar was noted in a few cases,

as well as the presence of small quantities of lime in the bonding material

(vicus Petra in Dobrogea, Kamen and Prisovo on the Danubian Plain); these

were prepared according to requirements, as evidenced by a square pit containing

more than 4 m3 of lime, discovered 9 m from the farmhouse in Prisovo .

The

thickness of bearing walls was 0.50-0.65 m and 0.80 m (exceptionally in

Kamen), while partition walls were about 0.45 m thick. Low foundations

or substructures supported walls erected of either mud brick or wattle-and-daub,

or tamped loess or clay in boarding formwork. The substructure of one of

the partition walls in Prisovo included rectangular kiln-baked bricks with

holes a few centimeters deep used to mount the vertical elements of a wooden

wall framework. Walls constructed in this manner were capable of supporting

not only a mud-coated roof of thatch, straw or branches, but also the much

heavier roofs made of fired tiles.

The roofing-tiles in use, usually c. 2.5 cm thick, included the flat type

with flanges (tegulae cum marginibus) as well as a gently arched so-called

Laconian type. The width of these roof tiles ranged from 27 to 39 cm, the

length from 43 to 69 cm. The usually semi cylindrical cover-tiles (imbrices

or calypteroi, to use a Greek term), which usually joined the tiles at the

top, were of appropriate length. The diameter of these tiles was from 12

to 18 cm. The technological revolution that occurred under Roman influence

– also impacted by the Greeks in the coastal areas - was reflected in the

common use of wrought iron nails, from 6.5 to 18 cm long, in the wooden

structure of the roof.

Kiln-baked bricks of square and rectangular shape were

also used for the hypocaust heating (Prisovo, Pavlikeni),

in the body of a furnace (?) for heating purposes (Fântânele) and in a pavement

(Kamen). Their length did not exceed 34 and the width 17 cm, while the thickness

usually oscillated around 4 cm. Bricks did not follow strictly the Roman

standards of size based on the foot = 0.296 m and referred more frequently

to the Greek linear standards. Bricks used for the pillars (pilae) supporting

the suspensura, i.e. the floor suspended above the hypocaust, in Prisovo

were up to 8 cm thick. At Pavlikeni warm air circulated in the hypocaust

cellar between vertical water-pipes which successfully replaced brick pillars

under the floor.

Kiln-baked bricks of square and rectangular shape were

also used for the hypocaust heating (Prisovo, Pavlikeni),

in the body of a furnace (?) for heating purposes (Fântânele) and in a pavement

(Kamen). Their length did not exceed 34 and the width 17 cm, while the thickness

usually oscillated around 4 cm. Bricks did not follow strictly the Roman

standards of size based on the foot = 0.296 m and referred more frequently

to the Greek linear standards. Bricks used for the pillars (pilae) supporting

the suspensura, i.e. the floor suspended above the hypocaust, in Prisovo

were up to 8 cm thick. At Pavlikeni warm air circulated in the hypocaust

cellar between vertical water-pipes which successfully replaced brick pillars

under the floor.

Room 5 in the villa-like building at Prisovo also

had heated walls. The heated inner face of the wall made of ceramic tiles

was separated from the stone outer walls by ceramic bobbins attached using

T-shaped elements.

At a few Dobrogean vicus-sites (T?gusor, vicus near Capidava

and Rasova-La Pesc?ie), situated relatively near the limes on the Danube

(cf. map), and at Butovo on the Danubian

Plain, as well as in the municipalized vicus at Ostrite Mogili (Municipium

Novensium - cf. plan), the bricks and

roofing-tiles found there bear the stamps of Moesian legions and auxiliary

troops

At a few Dobrogean vicus-sites (T?gusor, vicus near Capidava

and Rasova-La Pesc?ie), situated relatively near the limes on the Danube

(cf. map), and at Butovo on the Danubian

Plain, as well as in the municipalized vicus at Ostrite Mogili (Municipium

Novensium - cf. plan), the bricks and

roofing-tiles found there bear the stamps of Moesian legions and auxiliary

troops

This could possibly correspond to the presence in many vici of discharged

soldiers, a fact evidenced in inscriptions and by finds of military

diplomas (Fântânele, Mihai Bravu, Teli?-Amza, Butovo).

Around AD 200, some of the inhabitants of the Moesian

rural vici lived in houses of relatively high standard, often resembling

villas, which they doubtless wished to emulate. Testifying to this are

fragments

of painted plaster from Prisovo, marble elements of interior decoration

from Izvorul Mare and Capul Tuzla, stone bases and column shafts from

Fântânele,

Kurt Baiîr near Slava Cercheză Ivrinezu Mic, and the window glass from

Fântânele. In some of the vici, masonry wells and water-source facilities

were supplemented

with local water-supply systems making use of terracotta pipes.

Around AD 200, some of the inhabitants of the Moesian

rural vici lived in houses of relatively high standard, often resembling

villas, which they doubtless wished to emulate. Testifying to this are

fragments

of painted plaster from Prisovo, marble elements of interior decoration

from Izvorul Mare and Capul Tuzla, stone bases and column shafts from

Fântânele,

Kurt Baiîr near Slava Cercheză Ivrinezu Mic, and the window glass from

Fântânele. In some of the vici, masonry wells and water-source facilities

were supplemented

with local water-supply systems making use of terracotta pipes.

L. Kovalevska, T. Sarnowski (IAUW)

M. Bărbulescu, Viaţa rurală în Dobrogea romană (sec. I-III p. Chr.), Constanţa 2001

V.H. Baumann, Aşezări rurale antice în zona gurilor Dunării. Contribuţii arheologice la cunoaştera habitatului rural (sec. I-IV p. Chr.), Tulcea 1995

V.H. Baumann, Noi săpături de salvare în aşezarea rurală antică de la Teliţa-Amza, jud. Tulcea, Peuce 1 (14), 2003, 155 - 181

I. Cârov, Edin rimski vikus kraj selo Kamen, Izvestija na Istoričeski Muzej – V. Târnovo 12, 1997, 124 -133

V.N. Dinčev, Selata v dnešnata bâlgarska teritorija prez rimskata epocha (I – kraja na III vek), Izvestija na Nacionalnija Istoričeski Muzej 11, 2000, 185 - 218

A. i C. Opaiţ, T. Bănică, Das ländliche Territorium der Stadt Ibida (2.-7. Jh.) und einige Betrachtungen zum Leben auf dem Land an der unteren Donau, Die Schwarzmeerküste in der Spätantike und im frühen Mittelalter, Wien 1992, 103 -112

A. Suceveanu, Fântânele. Contribuţii la studiul vieţii rurale în Dobrogea romană Bucureşti 1998

B. Sultov, Edna villa rustica kraj s. Prisovo V. Târnovski okrâg, Izvestija na Okrâžnija Muzej V. Târnovo, 2, 1964, 49 - 64

The vicus is best evidenced for Moesia Inferior

(see map) and within its boundaries

for Dobrogea; it even determines a certain specificity of the province.

Testimony from Upper Moesia is sporadic, although there is no way of knowing

how little or many of the sources have survived. Therefore, the below reflections

on the religious cults of vicus inhabitants are largely relevant to Lower

Moesia.

The vicus is best evidenced for Moesia Inferior

(see map) and within its boundaries

for Dobrogea; it even determines a certain specificity of the province.

Testimony from Upper Moesia is sporadic, although there is no way of knowing

how little or many of the sources have survived. Therefore, the below reflections

on the religious cults of vicus inhabitants are largely relevant to Lower

Moesia.

Surviving religious dedications are mostly of official

character. Those erecting them were either vicus officials

(mostly magistri), or else specific groups

of inhabitants (all of the residents?) of a given vicus upon the initiative

of their officials. This state of affairs was reflected in the designations

cives Romani consistentes (settlers with Roman citizenship - cf.

photo), veterani et cives Romani consistentes (military settlers and

settlers with Roman citizenship), and veterani et cives Romani et Lai and/or

Bessi consistentes (military settlers and settlers with Roman citizenship

and the Lai and/or Bessi), vicani (vicus inhabitants) or Viconovenses (inhabitants

of Vicus Novus). Even so, there is no lack of inscriptions whose founders

were private individuals, acting upon their own initiative

|

|

| officials | Settlers with Roman citizenship |

.

Heading the ranking of worshipped deities is Jupiter

(Juppiter Optimus Maximus - cf.

photo). As a phenomenon, it is only natural, considering the "official"

character of the inscriptions. Jupiter symbolized the Roman state and religious

manifestations of homage to him were an expression of state loyalty. At

the same time, they may have been deemed a way of emphasizing the legal

and political status of the migrant population versus the autochthons. Juno

(Iuno Regina) also occurs in the inscriptions next to Jupiter, although

surprisingly seldom (four dedications from vicus Ulmetum, three from vicus

Secundini, one each from vicus Celeris, Turris Mucaporis, vicus Tautiomosis).

Not once is there any mention of Minerva, the third of the Capitoline divinities.

Perhaps the distinct emphasis on the Jupiter cult reflected a religious

veneration of the ruler, whose identification with Jupiter hardly needed

special justification. It should be made clear that a substantial part of

the surviving inscriptions were dedicated to Jupiter (and possibly to Juno)

"for the health" (pro salute) of the reigning emperor (two dedications from

vicus Trullensium, one each from vicus Ulmetum, vicus Quintionis, vicus

Secundini).

Heading the ranking of worshipped deities is Jupiter

(Juppiter Optimus Maximus - cf.

photo). As a phenomenon, it is only natural, considering the "official"

character of the inscriptions. Jupiter symbolized the Roman state and religious

manifestations of homage to him were an expression of state loyalty. At

the same time, they may have been deemed a way of emphasizing the legal

and political status of the migrant population versus the autochthons. Juno

(Iuno Regina) also occurs in the inscriptions next to Jupiter, although

surprisingly seldom (four dedications from vicus Ulmetum, three from vicus

Secundini, one each from vicus Celeris, Turris Mucaporis, vicus Tautiomosis).

Not once is there any mention of Minerva, the third of the Capitoline divinities.

Perhaps the distinct emphasis on the Jupiter cult reflected a religious

veneration of the ruler, whose identification with Jupiter hardly needed

special justification. It should be made clear that a substantial part of

the surviving inscriptions were dedicated to Jupiter (and possibly to Juno)

"for the health" (pro salute) of the reigning emperor (two dedications from

vicus Trullensium, one each from vicus Ulmetum, vicus Quintionis, vicus

Secundini).

Jupiter occurred also in association with other deities.

In vicus Quintionis he was identified with the Dolichenian Baal as Iuppiter

Dolichenus. At Vicus Ulmetum he was accompanied by Silvanus, who appears

to have enjoyed special popularity there. Also at Ulmetum Jupiter was worshipped

together with Hercules. At Giridava a votum was dedicated to Jupiter the

Best and Greatest and to all other gods and goddesses. From Topalu in Dobrogea,

where an ancient vicus of unidentified name was localized, there comes a

dedication to Jupiter associated with Juno and Ceres Frugifera. The same

goddess (Ceres Frugifera) was mentioned in an inscription from Tropaeum

Traiani along with Jupiter, Hercules Invictus and Liber Pater.

Deities occurring "independently",

that is, not in connection with Jupiter or Juno are very rare.

The worship of Liber (Liber Pater), an agricultural deity, identified with

Dionysus (Bacchus) is hardly surprising. From Troesmis comes an altar dedicated

to Jupiter and Liber Pater (Dionysus); similarly from Tropaeum Traiani,

there is one inscription mentioning Liber Pater next to Jupiter associated

with Hercules and  Ceres, and another one in which he is mentioned alone.

Naturally, dedications to Ceres (Ceres Frugifera) should also be linked

with the Liber Pater milieu. Undoubtedly close was the worship of Silvanus,

patron of the forests, but also of fields and pastures. Evidenced in Vicus

Ulmetum is an association (cultores) of the worshippers of this god with

the attribute "Sower" (Sator) and Sanctus. Further, a collegium Silvani

operated at Neat?nea in central Dobrogea. Evidence of a worship of this

deity was also recorded at Vicus Quintionis, where he appeared together

with the Nymphs.

Ceres, and another one in which he is mentioned alone.

Naturally, dedications to Ceres (Ceres Frugifera) should also be linked

with the Liber Pater milieu. Undoubtedly close was the worship of Silvanus,

patron of the forests, but also of fields and pastures. Evidenced in Vicus

Ulmetum is an association (cultores) of the worshippers of this god with

the attribute "Sower" (Sator) and Sanctus. Further, a collegium Silvani

operated at Neat?nea in central Dobrogea. Evidence of a worship of this

deity was also recorded at Vicus Quintionis, where he appeared together

with the Nymphs.

Hercules (cf.

photo) is frequently seen in Jupiter’s company (Tropaeum Traiani, Vicus

Ulmetum), but there is no dearth of dedications referring to him alone (Vicus

Quintionis, ?endreni). A vicus from the vicinity of Durostorum yielded an

inscription in homage of Mercury with the attribute Sanctus. A unique altar

found there was dedicated to the Auspicious Winds and the Good Gust of Wind.

In one case, we also find Mithra, mentioned as Deus Bonus Mithra, and similarly

Diana as Diana Optima.

Deities of Thracian origin, like the Thracian Rider-God, Sabasios or Megas

Theos are evidenced mostly by representations on votive tablets from numerous

vicus-sites in Dobrogea, northern Bulgaria, but also in Serbia (cf.

map). Only twice is there epigraphical evidence in the vici recorded

in inscriptions (cf. map) of the cult

of the Thracian Heros. The first is an inscription from Vicus Trullensium,

the second is from Vicus Ulmetum. In a Thracian rural sanctuary in V. T?novo-D?ga

L?a (cf. plan, reconstruction

and photo), south of Nicopolis ad

Istrum, there was found recently, however, a marble votive tablet showing

the Thracian horseman and bearing a Greek dedication to Heros. It says that

the votum was dedicated by the village (kome) with Thracian name Theolopara.

The population of Thracian origin, like the Bessi and

Lai in the Dobrogean vici Ulmetum, Secundini and Quintionis, for example,

was probably striving simultaneously for full assimilation (at least

in

official religious manifestations) in order to identify with broadly understood

Romanity. An excellent example of such an attitude is provided by the

votive

altars from vicus Quintionis, erected by the inhabitants regularly during

celebrations of the Italic feast of the Rosalia on June 13.

|

|

|

|

|

L. Mrozewicz, T. Sarnowski (IAUW)

M. Bărbulescu, Viaţa rurală în Dobrogea romană (sec. I-III p. Chr.), Constanţa 2001

I. Cârov, Niakoi aspekti na kulta kâm Trakijskija Konnik v regio Nicopolitana, Izvestija na Istoričeski Muzej – V. Târnovo 14, 1999, 78 - 87

B. Gerov, Zemevladenieto v Rimska Trakija i Mizija (I-III v.), Sofia 1980

E. Čerškov, Municipium DD kod Sočanice, Beograd 1970

T. Gerasimov, Edin chram na Trakijskija bog-konnik pri s. Lesičeri, Târnovsko, Studia in honorem K. Škorpil, Sofia 1961, 245 - 253

Z. Gočeva, M. Oppermann, Corpus Cultus Equitis Thracii, II1, II2, Leiden 1981, 1984

N. Hampartumian, Corpus Cultus Equitis Thracii, IV, Leiden 1979

G. Kacarov, Thrake (Religion), Real-Encyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, VI A, Stuttgart 1936, 472 - 551

G. Kacarov, Die Denkmäler des Trakischen Reitergottes in Bulgarien (Dissertationes Pannonicae II 14), Budapest 1938

K. Konstantinov, Trakijsko svetilište pri s. Draganovec, Târgoviško. Trakijski svetilišta. Trakijski pametnici (Monumenta Thraciae antiquae), II, Sofia 1980

M. Munteanu, Les divinités du panteon gréco-romain dans les villages de la Dobroudja romaine, Pontica 6, 1973, 73-86

D. Ovčarov, Trako-rimsko selište i svetilište na Apolon pri s. Gorno Ablanovo, Târgiviško, Archeologija 14, 1972, 46 - 55

P. Petrović, Inscriptions de la Mésie Supérieure. III 2. Timacum Minus et la Vallée du Timok, Beograd 1995

A. Suceveanu, Fântânele. Contribuţii la studiul vieţii rurale în Dobrogea romană Bucureşti 1998

A. Suceveanu, Al. Zahariade, Un nouveau vicus sur le territoire de la Dobroudja romaine, Dacia 30, 1986, 109 - 120

J. Todorov, Paganizmât v Dolna Mizija (prez pârvite tri veka sled Christa), Sofia 1928

Despite its fragmentariness, the

panorama of Moesian townships and villages, which emerges from an analysis

of available evidence, seems familiar enough. It also illustrates perfectly

well the Roman Empire’s role in the cultural

Despite its fragmentariness, the

panorama of Moesian townships and villages, which emerges from an analysis

of available evidence, seems familiar enough. It also illustrates perfectly

well the Roman Empire’s role in the cultural

development of the eastern and central European provinces. For a variety

of reasons, the urbanization of the North Balkans (cf.

map) with its distinctly pastoral model of economy before the arrival

of the Romans was much more limited than in neighbouring Pannonia or Noricum

(modern Hungary and Austria), for example; civilizational and cultural advancement

in vast areas of modern Serbia, Bulgaria and Romanian Dobrogea in the first

centuries AD was dependent primarily on the introduction and promotion of

new forms of rural settlement in these regions. An extremely important role

in this process, clearly stimulated by the Roman provincial administration,

was played by the rural, as well as semi-urban

vici.

They changed the landscape and the economic status of a significant

part of the Moesian provinces. It turned out that even after the Romans

had settled, in the first century AD, large tribal groups (cf. Native

tribes, Moesia c. 70, Tribal

capitals c. 150) of barbarians from beyond the Empire’s borders on the

Lower Danube, these vast lands were still capable of accepting many new

settlers, for example, from the overpopulated coasts of Asia Minor, creating

for them an attractive perspective of profitable economic enterprises and

practically universal development. All benefited from this situation,

including

the state, because with suitable taxing the population of the province

ensured not only economic self-sufficiency, but also the security of supplies

for

the thousands of Roman soldiers stationed on the limes.

|

|

|

| Native tribes | Moesia c. 70 | Tribal capitals c. 150 |

In the geographic and climatic conditions of Moesia,

at least some of the vici and komai offered apparently an attractive alternative

to urban life. The demography of many

townships and villages stands in proof, the local population being composed

of not only Thracians resettled from the south of modern Bulgaria already

in the first years of Roman presence on the Lower Danube and Getae of local

origin as well as resettled from beyond the Danube in the first century

AD. Also making up the population of these settlements were numerous veterans

and civilians coming in mostly from the Greek-speaking lands of the Empire.

Just as the  cultural status of the western provinces was shaped foremost

by the cities with their essential rural territories full of villas and

vici, so on the Lower Danube the small rural vici and komai (cf.

map), much more distant from the cities and legionary bases than, for

instance, in the German provinces or in Britain, played a much more important

role. In the bilingual or trilingual (Greek, Latin and Geto -Thracian) quasi-municipal

local communities, ethnic differences were gradually eradicated. With the

coming of a new mentality and a largely new world outlook and system of

values, this process led to the formation of a common, Roman-provincial

culture. For veterans and other newcomers from culturally more advanced

areas of the Empire settling in the Moesian villages, the vici were

primarily a place where they could put into life their family plans or get

wealthy. For the native residents (cf. Native

tribes, Moesia c. 70, Tribal

capitals c. 150), the vici became a place for education, in languages,

economy and technical know-how, as well as in self-government and the organization

of a varied social, cultural and religiouslife. The specificity of these

local communities within the greater cultural community of the northern

provinces of the Roman Empire depended on the considerable input of the

Greek-speaking element and a considerable variety of forms of social life.

cultural status of the western provinces was shaped foremost

by the cities with their essential rural territories full of villas and

vici, so on the Lower Danube the small rural vici and komai (cf.

map), much more distant from the cities and legionary bases than, for

instance, in the German provinces or in Britain, played a much more important

role. In the bilingual or trilingual (Greek, Latin and Geto -Thracian) quasi-municipal

local communities, ethnic differences were gradually eradicated. With the

coming of a new mentality and a largely new world outlook and system of

values, this process led to the formation of a common, Roman-provincial

culture. For veterans and other newcomers from culturally more advanced

areas of the Empire settling in the Moesian villages, the vici were

primarily a place where they could put into life their family plans or get

wealthy. For the native residents (cf. Native

tribes, Moesia c. 70, Tribal

capitals c. 150), the vici became a place for education, in languages,

economy and technical know-how, as well as in self-government and the organization

of a varied social, cultural and religiouslife. The specificity of these

local communities within the greater cultural community of the northern

provinces of the Roman Empire depended on the considerable input of the

Greek-speaking element and a considerable variety of forms of social life.

T. Sarnowski (IAUW)