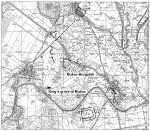

The

grave has been discovered by chance during earthmoving works during the construction

of a new road to Pasohlávky in autumn 1988. Later on its research has been undertaken

by the Regional Museum in Mikulov under the guidance of J. Peška. Originally

the grave was probably located on a small, gentle rise on the left bank of the

Thaya River, which has been made lower by gravel mining later on. The burial

site itself is located about 1.5 km to the south-southwest from the Roman military

fortification at the position of Hradisko (fig. 1). Despite a considerable dislocation

the research has succeeded in unearthing of a part of a large sepulchral chamber

in the shape of a rectangle with rounded corners and slightly narrowing walls

oriented in the northwest-southeast direction (ca 6 x 4 m). According to a great

number of both bigger and smaller stones including limestone from the near Pavlovské

Hills, some of them weighing 50 to 70 kg, inside of the sepulchral pit it may

be assumed that the burial chamber has been covered up with a wooden and stone

constructure. Marks of distortions on some of the bronze vessels caused probably

by the falling stones suggest that the sepulchre was originally hollow.

The

grave has been discovered by chance during earthmoving works during the construction

of a new road to Pasohlávky in autumn 1988. Later on its research has been undertaken

by the Regional Museum in Mikulov under the guidance of J. Peška. Originally

the grave was probably located on a small, gentle rise on the left bank of the

Thaya River, which has been made lower by gravel mining later on. The burial

site itself is located about 1.5 km to the south-southwest from the Roman military

fortification at the position of Hradisko (fig. 1). Despite a considerable dislocation

the research has succeeded in unearthing of a part of a large sepulchral chamber

in the shape of a rectangle with rounded corners and slightly narrowing walls

oriented in the northwest-southeast direction (ca 6 x 4 m). According to a great

number of both bigger and smaller stones including limestone from the near Pavlovské

Hills, some of them weighing 50 to 70 kg, inside of the sepulchral pit it may

be assumed that the burial chamber has been covered up with a wooden and stone

constructure. Marks of distortions on some of the bronze vessels caused probably

by the falling stones suggest that the sepulchre was originally hollow.

While

the big bronze vessels lying at the sides of the grave pit were quite well preserved

(fig. 2), an approximately squared secondary intervention outlined in the middle

was related to robbery in the grave. A number of greatly damaged iron, bronze

and glass objects have been found in almost all of the layers of this intervention.

The number of the individual finds successfully retrieved from this largely

damaged burial chamber has exceeded almost 180 pieces. It was ascertained that

apart from numerous artifacts its filling has contained remains of a greater

number of sacrificial animals, e.g. a one month's piglet, a goose, a hen, also

bones of a sheep, a goat etc. A part of a quartered, about 1.5 to 2 years old

calf was found at the south-eastern wall, close to a bronze suspended cauldron.

Anthropological analyses provide evidence that probably three persons have been

buried in this grave, one of them a female.

While

the big bronze vessels lying at the sides of the grave pit were quite well preserved

(fig. 2), an approximately squared secondary intervention outlined in the middle

was related to robbery in the grave. A number of greatly damaged iron, bronze

and glass objects have been found in almost all of the layers of this intervention.

The number of the individual finds successfully retrieved from this largely

damaged burial chamber has exceeded almost 180 pieces. It was ascertained that

apart from numerous artifacts its filling has contained remains of a greater

number of sacrificial animals, e.g. a one month's piglet, a goose, a hen, also

bones of a sheep, a goat etc. A part of a quartered, about 1.5 to 2 years old

calf was found at the south-eastern wall, close to a bronze suspended cauldron.

Anthropological analyses provide evidence that probably three persons have been

buried in this grave, one of them a female.

From

the chronological point of view is not without significance that the collection

includes some antiquated pieces which could have been passed on in a princely

Germanic family for a rather long time. It contains not only luxurious silver

vessels (fig. 3) some of them Augustan dating, but also early bronze and other

products such as a four legged table (fig. 4-5), a great decorative lamp (fig.

6), archaistic fittings and handle of a bucket of type E 24 (fig. 7-8), and

particularly an iron firedog of a late Celtic manner hitherto not encountered

in the Germanic princely graves from the 1st and 2nd centuries (fig. 9).

From

the chronological point of view is not without significance that the collection

includes some antiquated pieces which could have been passed on in a princely

Germanic family for a rather long time. It contains not only luxurious silver

vessels (fig. 3) some of them Augustan dating, but also early bronze and other

products such as a four legged table (fig. 4-5), a great decorative lamp (fig.

6), archaistic fittings and handle of a bucket of type E 24 (fig. 7-8), and

particularly an iron firedog of a late Celtic manner hitherto not encountered

in the Germanic princely graves from the 1st and 2nd centuries (fig. 9).

These are mostly artifacts that may be dated from at least the

late Republican and Augustan Periods to the years of Tiberius' and Nero's

rule. Although found in a much younger grave complex, they point probably

to the existence - sometime in the 1st century - of a Roman luxurious goods

consumers circle, perhaps members of the local Germanic nobility. They indicate

in thos way that a sort of a barbarian power centre could have been emerging

here at this early period. These facts lead naturally to another insistent

question of so far indefinable possible connection between this hoard and

the local Germanic elites about the mid 1st century. With utmost probability

such pieces could have been brought here only direct from Italy as gifts to

Germanic rulers or as a loot at the latest likely at the time of Vespasian

civil wars after the mid of the 1st century in which, as generally known,

German auxiliary troops with their kings Italicus and Sido from the area north

to the middle Danube were engaged.

Apart

from other objects about the age of which nothing can be said for certain

the greater part of the grave equipment inventory is of a younger dating,

falling into as late as the 2nd century, possibly even its latter part. This

also holds good for the majority of bronze vessels, especially for two cauldrons

(fig. 10). The first, a noticeably bulky piece with a rounded bottom part

and two circular handles, is a rather advanced variant of the older forms

of Eggers type 6 or 8. According to some parallels from the provincial territory

this is a shape that may be reckoned with most likely from as late as mid

2nd century. The same may be said about the other bronze cauldron with a deflected

neck and a more depressed, slightly cornered bulge. As for its shape it falls

within early cauldrons of Westland type which appear in the provinces during

the latter half of the 2nd and in the 3rd century (fig. 11).

Apart

from other objects about the age of which nothing can be said for certain

the greater part of the grave equipment inventory is of a younger dating,

falling into as late as the 2nd century, possibly even its latter part. This

also holds good for the majority of bronze vessels, especially for two cauldrons

(fig. 10). The first, a noticeably bulky piece with a rounded bottom part

and two circular handles, is a rather advanced variant of the older forms

of Eggers type 6 or 8. According to some parallels from the provincial territory

this is a shape that may be reckoned with most likely from as late as mid

2nd century. The same may be said about the other bronze cauldron with a deflected

neck and a more depressed, slightly cornered bulge. As for its shape it falls

within early cauldrons of Westland type which appear in the provinces during

the latter half of the 2nd and in the 3rd century (fig. 11).

However

there were four bronze circular handles fastened to its sides, connected with

the vessel by means of rests or attachments carried out in the form of realistic

busts of bearded Germans wearing Suebian buns (fig. 12). The attachments were

affixed in a very careless manner, and have fallen off the sides of the cauldron

in the grave. Therefore the utensils were not intended for a daily use; they

were rather a symbolic burial gift, while the attachments were made to order

directly for the Germanic ruler. But the cauldron bulb itself could have been

manufactured independently with the rests attached to it at a later date.

A large bronze bowl with omega-shaped handles and rhombic attachments, a bottom

of a bronze bucket, probably Eggers 28 type, and presumably also two low bronze

pots with stretched horizontal edge, a narrowed lower part and a tin-coating

of the inside also fall within the 2nd century.

However

there were four bronze circular handles fastened to its sides, connected with

the vessel by means of rests or attachments carried out in the form of realistic

busts of bearded Germans wearing Suebian buns (fig. 12). The attachments were

affixed in a very careless manner, and have fallen off the sides of the cauldron

in the grave. Therefore the utensils were not intended for a daily use; they

were rather a symbolic burial gift, while the attachments were made to order

directly for the Germanic ruler. But the cauldron bulb itself could have been

manufactured independently with the rests attached to it at a later date.

A large bronze bowl with omega-shaped handles and rhombic attachments, a bottom

of a bronze bucket, probably Eggers 28 type, and presumably also two low bronze

pots with stretched horizontal edge, a narrowed lower part and a tin-coating

of the inside also fall within the 2nd century.

The

weapons and military equipment which could be seen as insignia of the most

prominent war-chief of the tribe consist, however, only of a numerous set

of arrow - and spear-heads and lances, one of them inlaid with silver (fig.

13) and a fragment of a short one-cutting sword. A collection of 16 spurs,

some of them gold plated or with silver and gold inlays, corresponds with

the types which were common in numerous Germanic warrior-graves, dated almost

exclusively to the late 2nd century (fig. 14). The exceptional style components

of the burial equipment also include numerous belt fittings: the most spectacular

of these consisted of buckles, strap ends and a series of other ornaments

produced from gilded silver and adorned with filigree and graining (fig. 15-17).

They represent the same style of decoration as one of the pairs of spurs;

they were parts of one set (fig. 18). This type of belt fittings and spurs

apparently became a symbol of prestige confirming the special status of their

owner. While together with German shields with silver and gold plated fittings

(fig. 19) represented a typical equipment of the warrior, two golden capsule

pendants (fig. 17 on the right) produce evidence that one female person must

have been buried in the tombe probably at the same time.

The

weapons and military equipment which could be seen as insignia of the most

prominent war-chief of the tribe consist, however, only of a numerous set

of arrow - and spear-heads and lances, one of them inlaid with silver (fig.

13) and a fragment of a short one-cutting sword. A collection of 16 spurs,

some of them gold plated or with silver and gold inlays, corresponds with

the types which were common in numerous Germanic warrior-graves, dated almost

exclusively to the late 2nd century (fig. 14). The exceptional style components

of the burial equipment also include numerous belt fittings: the most spectacular

of these consisted of buckles, strap ends and a series of other ornaments

produced from gilded silver and adorned with filigree and graining (fig. 15-17).

They represent the same style of decoration as one of the pairs of spurs;

they were parts of one set (fig. 18). This type of belt fittings and spurs

apparently became a symbol of prestige confirming the special status of their

owner. While together with German shields with silver and gold plated fittings

(fig. 19) represented a typical equipment of the warrior, two golden capsule

pendants (fig. 17 on the right) produce evidence that one female person must

have been buried in the tombe probably at the same time.

The

connection with the Roman military milieu is evoked by the tear drop strap

end, a typical equipment of Antonine dating, fragments of iron scale armour

and probably quadrelup vaned, socketed arrow-head.

The

connection with the Roman military milieu is evoked by the tear drop strap

end, a typical equipment of Antonine dating, fragments of iron scale armour

and probably quadrelup vaned, socketed arrow-head.

A majority of other small objects are also worthy of a late chronological

classification and in contrast to the earlier propositions produce evidence,

that the definitive date of the committal and the time of deposition of the

entire find collection must have been the late 2nd century. It is worth noting

that the Germanic pottery occurring in the grave manifests numerous analogies

in the local settlement structures which are datable to the same period (fig.

20 in the backround).

![]() An

important component of the grave furniture consists of the finds which correspond

with the equipment of provincial graves, falling chronologically into the

first or second century. So-called surgical instruments (spatula probe) with

a sandstone tablet (fig. 21) and thick gold plated fittings of a table or

cabinet with relief images of Roman deities may be dated back roughly to the

half of the 2nd century (fig. 22). Numerous examples of glassware are also

unusual (fig. 23): outstanding among these are the fragments of set of eight

quadrangular bottles with handles and two glass pans - trullae. Fragments

of painted glass are not missing either; samples of a Roman provincial pottery

are relatively well represented, mostly by types which were not very usual

in the German milieu (fig. 20).

An

important component of the grave furniture consists of the finds which correspond

with the equipment of provincial graves, falling chronologically into the

first or second century. So-called surgical instruments (spatula probe) with

a sandstone tablet (fig. 21) and thick gold plated fittings of a table or

cabinet with relief images of Roman deities may be dated back roughly to the

half of the 2nd century (fig. 22). Numerous examples of glassware are also

unusual (fig. 23): outstanding among these are the fragments of set of eight

quadrangular bottles with handles and two glass pans - trullae. Fragments

of painted glass are not missing either; samples of a Roman provincial pottery

are relatively well represented, mostly by types which were not very usual

in the German milieu (fig. 20).

The above statements has brought a re-appraisal of the Roman-Germanic

interrelation during the military affairs of the latter half of the 2nd century,

called Marcomannie wars. The burial furniture contains a unique body of material

illuminating the lifestyle and status of a Germanic chieftain under the Roman

control. Besides the exceptional collection of silver and bronze vessels,

a series of extraordinary burial goods, e.g. a bronze lamp, a bronze offering

table, a set of spatula probe, a number of Roman pottery and glass vessels

and other pieces, which are characteristic of Roman burial customs in the

provinces, produce evidence to the transfer of Roman belief in life after

death. The splendid silver and bronze vessels, as well as examples of Roman

furniture, might have originated as gifts from the Roman authorities to a

Germanic ally. It seems very likely that through such a personage, probably

a local king, a head of the pro-Roman party, who was probably appointed to

this dignity by the Romans at the time of the Marcomannic wars, some kind

of Roman political influence has been exerted in order to establish convenient

conditions for the further firming of Roman rule over the occupied territory.