The term ‘southern Upper Germany’ covers the territories of the Lingones and Sequani in eastern France, along with the Rauraci and Helvetii in western Switzerland and the upper Rhine. The southern Limes area shows some affinity with these regions.

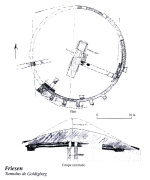

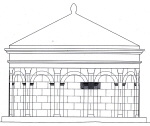

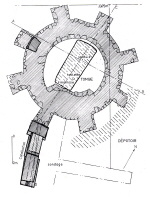

In contrast to northern Upper Germany only a few isolated tumuli (here meaning round barrows on a stone tambour or drum) have been discovered, and no distinct barrow culture seems to have existed in the area. The most noteworthy is the Flavian tumulus at Augusta Raurica/Augst. At 15m in external diameter (it was probably intended to be 50 Roman feet) and with an original height of around 10m, this is one of the largest graves on the Rhine, but it is still smaller than similar structures in the Gallic coloniae. The tumulus at ’La Gironette’ near Augustodunum/ Autun, for example, was nearly twice as big, although that outside Arausio/Orange was only marginally larger. More important than its sheer size was its position on a marked spur immediately in front of Augst’s impressive east gate. This lay on the main road to Vindonissa, and the main roadside necropolis only began once the spur had been passed. No inscription has survived, but such a prominent position would suggest that the person buried was the recipient of a public funeral (funus publicum). There is additional evidence to support such a hypothesis, for only one grave was found inside it: an off-centre bustum (a cremation on the site of the funeral pyre) of a male who was probably 35-40 years old. The monument is thus later than the burial itself and so cannot have been constructed during the deceased’s lifetime, as so many other monuments were. Hence it is more likely to be the result of a public decree, which stood in public space. This type of round grave was still considered a particularly ‘aristocratic’ form in the 1st century AD and so would have been appropriate for an honorific tomb. A grave inscription from Avenches (see below) expressly mentions a funus publicum for a member of the Helvetian upper class and, in the case of Augst, we can only surmise that the dead man belonged to one of the leading families. No expensive grave goods were found, even amongst burnt goods from the pyre, but three amphorae are worth mentioning, which had a capacity of c. 80 lt of wine. The grave furniture otherwise seems rather humble, which is in keeping with the Italo-Roman tradition. The monument’s construction follows a Mediterranean pattern, with gravel filled relieving arches, strengthening cross-walls and a massive central support for a crowning pinecone or statue. The remains show that the tambour (or drum), and possibly the enclosure wall, was colourfully decorated with lime and sandstone. A pottery kiln found between the tumulus and its enclosure wall shows that the site had lost its sacred character by c. 200 AD and its final destruction dates to the start of the 4th century (Schaub 1992, 77-102).

Another variant of the tumulus tomb

is the barrow at Friesen in south-east Alsace (Raurican territory). Its opus reticulatum enclosure wall was 25m in external diameter and still stood 75cm high when it

was excavated in 1964/5. The weight of the earth barrow was contained by radial

buttresses, rather than internal relieving arches, and these stub walls may

have born columns or tomb guardian sculptures. The tumulus is thought to have

been 7-8 m high and, on balance, it seems that the tambour wall was probably

lower than its counterpart at Augst. It dates from 50-100 AD and formed the

centrepiece of a villa cemetery (Landes 2002, 40 u. 70).

Another variant of the tumulus tomb

is the barrow at Friesen in south-east Alsace (Raurican territory). Its opus reticulatum enclosure wall was 25m in external diameter and still stood 75cm high when it

was excavated in 1964/5. The weight of the earth barrow was contained by radial

buttresses, rather than internal relieving arches, and these stub walls may

have born columns or tomb guardian sculptures. The tumulus is thought to have

been 7-8 m high and, on balance, it seems that the tambour wall was probably

lower than its counterpart at Augst. It dates from 50-100 AD and formed the

centrepiece of a villa cemetery (Landes 2002, 40 u. 70).

A small, supposedly Roman built barrow, with no stone tambour, was excavated near Ellikon (Kt. Zürich) in 1985, and contained several Roman graves (Hedinger 1996). Secondary burials have also been noted in prehistoric barrows, however, for example at Lembach, Oberlauchringen and Tiengen and could represent immigrants from regions where barrow burials were still current (Trumm 2002, 173).

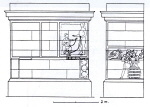

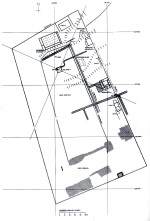

The two largest multi-storey mausolea yet excavated in southern Upper Germany lay along a by-road to the north-east of the Helvetian civitas capital Aventicum/Avenches (Castella 1998; Castella 1999; Castella 2002; Bossert 2002). Dendro-chronology of oak piles from beneath the northern foundations of one of the monuments produced a felling date of c. 30 AD, and such a context is sufficient to date the mausoleum as a whole. The larger of the two structures was probably about 25m high and its semicircular ground plan is so far unique in the province, although common for high-ranking people in Mediterranean areas. The many architectural fragments found allow us to reconstruct a combination of an exedra (cf. grave monuments in Raetia) and a mausoleum of the Poblicius-Type (cf. Grave monuments in Lower Germany). The monument was crowned by a temple, which is likely to have contained statues of the deceased. Rreconstructions give some impression of the colourful painted decoration on Roman grave monuments.

As already implied, the mausolea were not part of an Italian style ‘urban’

street necropolis. Instead they formed the centrepiece of a private cemetery

with three adjoining grave enclosures, which originally seem to have been

part of a rich villa suburbana. The two southern enclosures contained relatively manageable numbers of graves,

but the northern area was intensively used, with over 200. Apart from the

stone foundations of two small funerary shrines (?), no grave monuments were

found and this may have been a servants' cemetery in the shadow of the owners'

tombs. The southern monument was decorated with

carved reliefs, including ornamental shields (clipei) on its base.

As already implied, the mausolea were not part of an Italian style ‘urban’

street necropolis. Instead they formed the centrepiece of a private cemetery

with three adjoining grave enclosures, which originally seem to have been

part of a rich villa suburbana. The two southern enclosures contained relatively manageable numbers of graves,

but the northern area was intensively used, with over 200. Apart from the

stone foundations of two small funerary shrines (?), no grave monuments were

found and this may have been a servants' cemetery in the shadow of the owners'

tombs. The southern monument was decorated with

carved reliefs, including ornamental shields (clipei) on its base.

This motif was borrowed from triumphal architecture and can be

found i.a. in the Forum of Augustus at Rome. Upper German grave architecture

only used the design in exceptional cases, however, and they are more common

in the neighbouring province of Gallia Narbonensis to the south, especially

in the Geneva area (Bossert 2002, 70).

This motif was borrowed from triumphal architecture and can be

found i.a. in the Forum of Augustus at Rome. Upper German grave architecture

only used the design in exceptional cases, however, and they are more common

in the neighbouring province of Gallia Narbonensis to the south, especially

in the Geneva area (Bossert 2002, 70).

These impressive grave monuments formed the centrepieces of two enclosed

family cemeteries, each of which had several cremations and inhumations grouped

around the monuments, along with the remains of funeral pyres. The monuments'

dimensions were in keeping with an exclusive position on the opposite side

of the road from two Gallo-Roman temples, surrounded by temenos walls.

The grave of an Augustan period women was discovered beneath the cella of one

of these temples, and so it seems likely that they too developed from

a funerary cult. Coins continued to be deposited here into the 4th century,

which suggests that this must have been more than a purely private, family

commemoration and we may be seeing a founder or hero cult similar to Mediterranean

examples. The proximity of the mausolea to what may have been an ancestral

cult at least local importance, would thus further underline their importance.

Sadly, no inscriptions survive and so we can only speculate as to the social

rank of the deceased. But, again, the monuments' size and position is suggestive.

Two mid 1st century AD grave inscriptions from Avenches refer to two men who must have been part of the elite of the civitas. As the actual inscribed slabs had been removed from their tombs in post-Roman times and reused elsewhere, nothing can be said about their original contexts. As a result, there is nothing to link them to the "En Chaplix" mausolea, but they do show the sort of person who might have been involved in the construction of such monuments. The inscriptions read as follows:

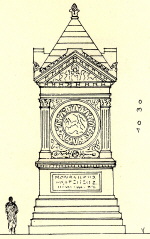

1. Inscribed slab of 73 x 56 x 3-5 cm

[C(aio) I]ul(io) C(ai) f(ilio) Fab(ia) Camil/[lo s]ac(erdoti) Aug(usti)/ mag(no) / [trib(uno)] mil(itum) leg(ionis) IIII Maced(onicae) / [hast]a pura et cor(ona) aur(ea) / [dona]to a T(iberio) Claud(io) Caes(are) / [Aug(usto) ite]r(um) cum ab eo evocatus / [in Brita]nnia militasset Iul(ia) / [Ca]milli fil(ia) Festilla / ex testamen(to). 'For Gaius Julius Camillus, son of Gaius, of the Fabian tribe, priest in chief of the Imperial cult, Military tribune of Leg. IIII Macedonica, twice decorated with the silver spear and gold crown by Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus, when he served as remobilized veteran under his command in Britain. Iulia Festilla, daughter of Camillus had this built in accordance with his will'. (Walser 1979 Nr. 87) |

2. Inscribed slab of 75 x 72 x 27 cm

C(aio) Valer(io) C(ai) f(ilio) Fab(ia tribu) Ca/millo quoi publice / funus Haeduorum / civitas et Helvet(i) decre/verunt et civitas Helvet(iorum) / qua pagatim publice / statuas decrevit / I[u]lia C(ai) Iuli Camilli f(ilia) Festilla / ex testamento. (Walser 1979 Nr. 95). 'For Gaius Valerius Camillus, son of Gaius, of the Fabian tribe, for whom the civitas of the Haedui and the (comunity of the) Helvetii decreed a public funeral and for whom the civitas of the Helvetii, by a vote in its districts, decreed the erection of statues. Julia Festilla, daughter of Caius Julius Camillus had this built in accordance with his will' |

The Camilli were probably Avenches' most influential family. Their best known ancestor was mentioned in Latin literature as a partisan of Caesar, and was involved in the execution of Decimus Brutus, one of Caesar's murderers (Frei-Stolba/Bielman 1996, 2 u. 36-39). The two people named in the inscriptions belonged to different branches of the family, as is shown by the different gentil names of Iulius and Valerius, which were granted as part of the award of Roman citizenship. In addition to the grave inscription, we also have the base for an honorific statue of the tribune C. Iulius Camillus, whose inscription provides the same information (Walser 1979 Nr. 86). This was removed in the Middle Ages, so its original location (e.g. by the tomb or on the forum?) is unknown. Both monuments offer an amazing parallel with those of the eques Romanus Cl. Paternus Clementianus, in Epfach (cf. grave monuments in Raetia). C. Valerius Camillus' influence obviously extended far into neighbouring Gallia Lugdunensis, for the Haedui who joined with the Helvetii to degree his public funeral came from this province.

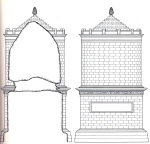

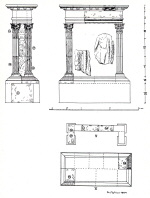

Another mausoleum, at Wavre (Kt. Neuchâtel), shows links to the large Avenches- "En Chaplix" monuments, because of its U-shaped ground plan. It is markedly smaller, however, rising to 10m high on a 3.6 x 3.5m base. It had a small internal vault or room to house the burial containers (e.g. ash cists or stone urn), but there was clearly no central grave, which supports a hypothesis that the burial lay above ground. It is not certain whether its front entrance was openly accessible, or blocked by a door, but numerous architectural fragments allow a two storey mausoleum with pediment and acroters to be reconstructed. Several of the fragments derive from three c. 1.4 times live size statues of the deceased, which probably stood in a temple storey. These include a hand holding a scroll (volumen), which is typical of classical togate statues and usually indicates Roman citizenship. The monument stood in the 13 x 13m enclosure of a villa cemetery and can be dated on stylistic grounds to the first half of the 2nd century AD (Bridel 1976).

The mausoleum at Delémont (Kt. Jura)

must have had similar dimensions, to judge from its 4 x 2.3m concrete base

and the numerous small architectural and statue fragments found. It too sat

in a (17 x 18.5 m) walled villa cemetery (Légeret 2000, 235).

The mausoleum at Delémont (Kt. Jura)

must have had similar dimensions, to judge from its 4 x 2.3m concrete base

and the numerous small architectural and statue fragments found. It too sat

in a (17 x 18.5 m) walled villa cemetery (Légeret 2000, 235).

![]()

A set of relief carved blocks from Basilia (Basel) are more difficult

to interpret, as they were found away from their original context. They show

soldiers with a captive, and similar scenes are known from a number of Upper

German grave monuments: for example on the side panels of the niche monuments

of Nickenich, and the pillar monuments of Stuttgart-Zazenhausen (Klatt 1996;

Meyer 1998). Nevertheless, it remains contentious whether they represent a

1st century grave or a 1st or 2nd century victory monument (Neukom 2002, 114-117).

A set of relief carved blocks from Basilia (Basel) are more difficult

to interpret, as they were found away from their original context. They show

soldiers with a captive, and similar scenes are known from a number of Upper

German grave monuments: for example on the side panels of the niche monuments

of Nickenich, and the pillar monuments of Stuttgart-Zazenhausen (Klatt 1996;

Meyer 1998). Nevertheless, it remains contentious whether they represent a

1st century grave or a 1st or 2nd century victory monument (Neukom 2002, 114-117).

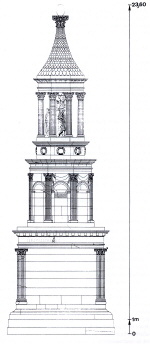

We now turn to the territory of the east Gallic Lingones, in south-western

Upper Germany. Here a three-storey mausoleum stood at Faverolles, on a long-distance

road near the tribe's civitas capital Langres. It probably belonged to the cemetery of a large villa and,

like the Poblicius-Monument in Cologne (which was only half the size), a substantial

part of the original architecture (c. 5%) has survived. These fragments permit

a fairly reliable reconstruction of a tower-like structure, reminiscent of

southern Gallic mausolea (Walter 2000) such as the so-called 'Julii-monument'

in Glanum near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and similar monuments near Orange, Aix-en-Provence and Nîmes (Landes 2002). It would originally have stood 23.6m high. Its upper storey

would have formed a round colonnaded temple (tholos), and the Avenches-"En Chaplix" and Faverolles monuments make up three of the northernmost examples of these

three-story, tower-like mausolea.

We now turn to the territory of the east Gallic Lingones, in south-western

Upper Germany. Here a three-storey mausoleum stood at Faverolles, on a long-distance

road near the tribe's civitas capital Langres. It probably belonged to the cemetery of a large villa and,

like the Poblicius-Monument in Cologne (which was only half the size), a substantial

part of the original architecture (c. 5%) has survived. These fragments permit

a fairly reliable reconstruction of a tower-like structure, reminiscent of

southern Gallic mausolea (Walter 2000) such as the so-called 'Julii-monument'

in Glanum near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and similar monuments near Orange, Aix-en-Provence and Nîmes (Landes 2002). It would originally have stood 23.6m high. Its upper storey

would have formed a round colonnaded temple (tholos), and the Avenches-"En Chaplix" and Faverolles monuments make up three of the northernmost examples of these

three-story, tower-like mausolea.

Four almost life sized grave statues are known from Monthureux-sur-Saône, right on the border with the Belgian tribe, the Leuci. Their architectural context is unknown (Castorio 2000, 118 f.) and they may have stood in a mausoleum, grave garden or funerary temple, but they could be linked with the inscription from the grave of a certain Sextus Iulius Senovir.

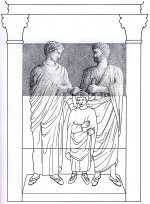

In addition to the tower-like mausolea inspired by southern Gaul in the vicinity

of the civitas capitals of Avenches and Langres, further

differences in grave architecture can be noted, which set southern Upper Germany

apart from northern part of the province. In particular, pillar monuments

in the style of

the "Igeler Säule" become increasingly rare. Individual examples certainly existed, and a prime

example is a block from Avenches, carved with a relief with a family scene

(Bossert 1988, 81 f.). But they never became such a dominant type as they did

amongst the 2nd and 3rd century grave monuments of northern and central Upper

Germany. Mausolea with funerary statues, on the other hand, continued to be

built in the area well into the 2nd century.

In addition to the tower-like mausolea inspired by southern Gaul in the vicinity

of the civitas capitals of Avenches and Langres, further

differences in grave architecture can be noted, which set southern Upper Germany

apart from northern part of the province. In particular, pillar monuments

in the style of

the "Igeler Säule" become increasingly rare. Individual examples certainly existed, and a prime

example is a block from Avenches, carved with a relief with a family scene

(Bossert 1988, 81 f.). But they never became such a dominant type as they did

amongst the 2nd and 3rd century grave monuments of northern and central Upper

Germany. Mausolea with funerary statues, on the other hand, continued to be

built in the area well into the 2nd century.

Several architectural fragments from Dijon are known that show relief scenes from the everyday lives of the deceased, and these isolated pieces could be ascribed to pillar monuments by analogy to Rhenish and Treveran examples.

However, they might just as probably represent the remains of oversized tombstones (stelae) or parts of impressive, façade- like grave garden frontages. One monument from Til-Châtel near Dijon is exceptional in this context, and commemorates a wine merchant with a grave in the shape of a shop front. But, although another example is known from Dijon, this form of grave monument is unknown on the Rhine and upper Danube (Langner 2002, 329-337).

Monolithic pediments, more than 1m wide are known, and seem likely to have topped large stelae, shrines (aediculae) or niche monuments. Examples of such monuments are known from Augst (Bossert-Radtke 1992, 100 f) and from Lingonian territory, but niche monuments from the north of the province usually lacked pediments, what might just due to preservation.

In contrast to the 1st century Rhineland

and Raetia, grave gardens and enclosure ditches do not seem to have been universal

in Helvetian

territory

(Hintermann 2000, 44). In addition to the walled mausolea enclosures discussed

above, enclosing hedges and ditches are known as cemetery bounderies, for example

at Weil am Rhein (Kr. Lörrach;

Asskamp 1989, 16 f.), but they are less common around single graves. Examples

of individual enclosures are known from Vindonissa,

In contrast to the 1st century Rhineland

and Raetia, grave gardens and enclosure ditches do not seem to have been universal

in Helvetian

territory

(Hintermann 2000, 44). In addition to the walled mausolea enclosures discussed

above, enclosing hedges and ditches are known as cemetery bounderies, for example

at Weil am Rhein (Kr. Lörrach;

Asskamp 1989, 16 f.), but they are less common around single graves. Examples

of individual enclosures are known from Vindonissa, where the excavated cemeteries

along the roads running south, west and north from the fortress show significant

differences. Those in the south and west had rather humble graves and only

a few grave monuments.

where the excavated cemeteries

along the roads running south, west and north from the fortress show significant

differences. Those in the south and west had rather humble graves and only

a few grave monuments.  Only the north had a roadside necropolis on the original

classical/ Italian model, and this was obviously the town's preferred, elite

burial ground. Several rectangular 40-50cm wide strip foundations are known

from grave shrines (aediculae) or enclosure walls, but most of these buildings were deliberately destroyed

in the last third of the 1st century AD. This shocking sacrilege must have

had a specific reason, and there may be a link to the well attested damnatio memoriae of the 21st legion after its shameful conduct during the year of the four Emperors

in 69AD. The devastation is clearly visible on statues, such as the small head

of a sphinx (?) and the body of a triton (?), which had been intended as grave

guardians (Bossert 1999, Nr. 18-19). Remarkably, though, the Vindonissa cemeteries

all contained male and female burials and so the north cemetery was not just

the preserve of soldiers.

Only the north had a roadside necropolis on the original

classical/ Italian model, and this was obviously the town's preferred, elite

burial ground. Several rectangular 40-50cm wide strip foundations are known

from grave shrines (aediculae) or enclosure walls, but most of these buildings were deliberately destroyed

in the last third of the 1st century AD. This shocking sacrilege must have

had a specific reason, and there may be a link to the well attested damnatio memoriae of the 21st legion after its shameful conduct during the year of the four Emperors

in 69AD. The devastation is clearly visible on statues, such as the small head

of a sphinx (?) and the body of a triton (?), which had been intended as grave

guardians (Bossert 1999, Nr. 18-19). Remarkably, though, the Vindonissa cemeteries

all contained male and female burials and so the north cemetery was not just

the preserve of soldiers.

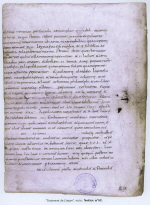

The situation is different in Lingonian territory, where we even have

an epigraphic source that explicitly mentions the construction of a grave garden.

This is the so-called "Testament of the Lingonian", a lengthy grave inscription known only from a Medieval copy. It records the

last will of a rich Gaul and concerns the provisions he made for his funeral,

monument and grave goods (Le Bohec 1991).

The situation is different in Lingonian territory, where we even have

an epigraphic source that explicitly mentions the construction of a grave garden.

This is the so-called "Testament of the Lingonian", a lengthy grave inscription known only from a Medieval copy. It records the

last will of a rich Gaul and concerns the provisions he made for his funeral,

monument and grave goods (Le Bohec 1991).

The enclosure walls of two grave gardens at Nod-sur-Seine, near Châtillon-sur-Seine (Burgundy), are an archaeological parallel to this source. The enclosures measure 10 x 12m and 10 x 8m respectively, with niche-like annexes. They may have been roofed as small shrines (aediculae), but an open reconstruction cannot be ruled out. Several sculptural fragments were recovered during excavations, including a statue that may portray the deceased (Renard 1993; Landes 2002, 48 f). The ‘Testament of the Lingonian’ does mention the erection of a statue of the dead in a grave garden.

Grave altars (arae)

are as common in the south of the province as the north, especially in the

area around Avenches.

As in the Rhineland and Raetia, they appear to have been absent before the

mid 2nd century, with the possible exception of one from the legionary base

Vindonissa/Windisch. This pulvinus-fragment has been tentatively dated to

the late 1st century and, if that is correct, the monument would presumably

just

reflect the personal taste of a legionary from Italy (Bossert 1999, 51 f).

Another grave altar from Avenches was commissioned by members of a goldsmith’s

family from Lydia in Asia Minor (Walser 1979 Nr. 117).

Grave altars (arae)

are as common in the south of the province as the north, especially in the

area around Avenches.

As in the Rhineland and Raetia, they appear to have been absent before the

mid 2nd century, with the possible exception of one from the legionary base

Vindonissa/Windisch. This pulvinus-fragment has been tentatively dated to

the late 1st century and, if that is correct, the monument would presumably

just

reflect the personal taste of a legionary from Italy (Bossert 1999, 51 f).

Another grave altar from Avenches was commissioned by members of a goldsmith’s

family from Lydia in Asia Minor (Walser 1979 Nr. 117).

Another characteristic of Helvetian

and Sequanian territory is the frequent association (or even combination) of

cemeteries with sanctuaries.

The phenomenon

is also sometimes present in the southern Limes area, e.g. at Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt and Rottenburg. Deposits of funerary sculpture

and architectural fragments have been found in the cemetery areas at both

places. These had been assembled in post-Roman times and included a dedication

to Herecura,

the goddess of the underworld, whose sanctuaries are often found near cemeteries

(Meyr 2000).

Another characteristic of Helvetian

and Sequanian territory is the frequent association (or even combination) of

cemeteries with sanctuaries.

The phenomenon

is also sometimes present in the southern Limes area, e.g. at Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt and Rottenburg. Deposits of funerary sculpture

and architectural fragments have been found in the cemetery areas at both

places. These had been assembled in post-Roman times and included a dedication

to Herecura,

the goddess of the underworld, whose sanctuaries are often found near cemeteries

(Meyr 2000). In addition to Avenches, the mausoleum at Chavéria

(Dep. Jura, F) in Sequani territory, can also be used as an example. To judge

from its 5.2 x 4.4m foundations, it may have been somewhat larger than those

from Wavre and Délemont. The upper storey was probably an open four sided temple (tetrastylos) and it stood in a 17.5 x 11.1m walled cemetery, next to a sanctuary and a small

settlement, that probably provided maintenance (CAG 39, 294 f.). The mausoleum

was a later (c. late 2nd century) addition to a pre-existing cemetery, but

how it relates to the neighbouring sanctuary, remains unclear.

In addition to Avenches, the mausoleum at Chavéria

(Dep. Jura, F) in Sequani territory, can also be used as an example. To judge

from its 5.2 x 4.4m foundations, it may have been somewhat larger than those

from Wavre and Délemont. The upper storey was probably an open four sided temple (tetrastylos) and it stood in a 17.5 x 11.1m walled cemetery, next to a sanctuary and a small

settlement, that probably provided maintenance (CAG 39, 294 f.). The mausoleum

was a later (c. late 2nd century) addition to a pre-existing cemetery, but

how it relates to the neighbouring sanctuary, remains unclear.

Another example is the villa cemetery

at Poligny (33.5 x 26.5 x 32 x 22.5 m in size), to the east of Dole, in Sequani

territory. In one corner of the walled cemetery the 4.65m strip foundations

of a square

grave monument were

found, which is best reconstructed as resembling a temple. This burial ground,

too, lay in the immediate neighbourhood of a sanctuary with a pronaos-temple (CAG 39 Jura, 570).

Another example is the villa cemetery

at Poligny (33.5 x 26.5 x 32 x 22.5 m in size), to the east of Dole, in Sequani

territory. In one corner of the walled cemetery the 4.65m strip foundations

of a square

grave monument were

found, which is best reconstructed as resembling a temple. This burial ground,

too, lay in the immediate neighbourhood of a sanctuary with a pronaos-temple (CAG 39 Jura, 570).

The walled family burial ground at the villa of Biberist-Spitalhof (Kt.

Solothurn) occupies an unusual position (Schucany 1995; Schucany 2001). For

it lay centrally within the estate's large internal courtyard (c. 70m from

the pars urbana), rather than outside the walled villa enclosure, as elsewhere.

Strictly speaking, this should be a breach of ancient Roman funerary law, but

graves have also been found close to the main houses of other Helvetian villas,

and these burial laws were apparently interpreted flexibly. At the west end

of the cemetery a bustum was found for three individuals who had been buried

at the same time (a man of c. 50, a woman and a new-born baby). This was marked

by a 2.13m high stelae with an halved column. The position just inside the

villa area suggests the grave of a founder, similar to Avenches- "En Chaplix". Evidence for a later exhumation (and reburial) may be linked to a change in

ownership after the third quarter of the 2nd century, and a stone urn shows

influence from Gaul, where they are common. Bierbach in the Palatinate, which

was situated on Mediomatrici territory in Gallia Belgica, has also produced

an impressive grave monument, this time immediately in front of the villa's

main façade.

The walled family burial ground at the villa of Biberist-Spitalhof (Kt.

Solothurn) occupies an unusual position (Schucany 1995; Schucany 2001). For

it lay centrally within the estate's large internal courtyard (c. 70m from

the pars urbana), rather than outside the walled villa enclosure, as elsewhere.

Strictly speaking, this should be a breach of ancient Roman funerary law, but

graves have also been found close to the main houses of other Helvetian villas,

and these burial laws were apparently interpreted flexibly. At the west end

of the cemetery a bustum was found for three individuals who had been buried

at the same time (a man of c. 50, a woman and a new-born baby). This was marked

by a 2.13m high stelae with an halved column. The position just inside the

villa area suggests the grave of a founder, similar to Avenches- "En Chaplix". Evidence for a later exhumation (and reburial) may be linked to a change in

ownership after the third quarter of the 2nd century, and a stone urn shows

influence from Gaul, where they are common. Bierbach in the Palatinate, which

was situated on Mediomatrici territory in Gallia Belgica, has also produced

an impressive grave monument, this time immediately in front of the villa's

main façade.

One peculiar habit of marking graves at the surface was monolithic, man-sized grave stones in the form of narrow pyramid stumps. These were largely confined to south- western Upper Germany and the distribution centres on the c. 40 examples around Dijon and a few more found near Andemantunum/Langres (Joubeaux 1989).

With one exception from Langres, the monuments do not carry relief decoration, but have smooth outer surfaces, and were thus comparatively low-key in appearance. The regional pattern is matched by indigenous Gallic names on the inscriptions (Le Bohec 2003, 90 ff) and, interestingly, the term monumentum is attested for the markers, e.g. m(onumentum) Lit/uge/ni, Bi/racati (filii): "'The grave of Litugenus, son of Biracatus" (Le Bohec 2003 Nr. 114).

The origins of this burial habit remain partially unresolved. On the one

hand, they seem likely to relate back to pre-Roman, Celtic obelisks, but there

is a chronological hiatus between these and the pyramid stelae which, although

difficult to date, are usually assigned to the period 50-200 AD. It is possible

that the equivalent early Roman monuments were predominately made of wood and

have thus disappeared.

The origins of this burial habit remain partially unresolved. On the one

hand, they seem likely to relate back to pre-Roman, Celtic obelisks, but there

is a chronological hiatus between these and the pyramid stelae which, although

difficult to date, are usually assigned to the period 50-200 AD. It is possible

that the equivalent early Roman monuments were predominately made of wood and

have thus disappeared.

Some of these pyramids have been found far into western Switzerland, for example at Martigny and Nyon, and it is conceivable that they may be connected to immigrants from Lingonian territory. The pyramidion from Nyon probably stood on a grave with no other substructure and there is certainly no evidence that it formed part of a finial for a larger monument. Strictly speaking it was a pyramid stela, but in marked contrast to the dimensions of other examples, it is currently the smallest grave monument known from Upper Germany: all of 22.5 cm high.

|

A further unusual custom on Lingonian territory were stelae with arched niches and surrounding inscriptions. |

Funerary stelae in the shape of houses or miniature grave monuments are found

further north, on the territory of the Leuci, in Gallia Belgica. The

example of these small monuments can be seen as an influence in the territory

of the neighbouring Lingones in Upper Germany (Burnand 1990,

189). |

In Alsace, a specific variety of hut-shaped gravestones can be found, that imitated tent-like structures, thatched huts or houses. Originally, these were probably put on a base over the grave and had inscriptions cut into their fronts. More sophisticated examples from Tres Tabernae/Zabern had a shield-like frontage with an opening for offerings or oil lamps (Forrer 1918, 60 f.). The container for the cremation ashes was usually put under the main structure.

Cremation (busta and urn graves) was the most common rite amongst the burials found around the mausolea discussed above. Indeed, only the Avenches- "En Chaplix" cemetery contained inhumations.It was used into the mid 3rd century. Almost regular ash or sacrificial pits/shafts are known (fosses à offrandes/ dépotoirs; Castella 2002) and one such sacrificial shaft, next to the Chavéria mausoleum, contained fragments of 82 vessels. These burials tend to have disproportionately rich grave goods, in keeping with Celtic ideas on the afterlife. The normally sumptuous provision of table ware, drinking vessels and amphorae correspond with decorated relief, which frequently evoke Bacchic motifs (wine and love) (Bossert 2002, 71). Indeed, the Celtic belief in an afterlife that focused on a continued earthly existence, was materially different to the Graeco-Roman topoi of a happy eternity in Elysium. A certain preference for Attis is apparent amongst the mythological relief scenes from Avenches, Nyon and other sites in southern Germania Superior. The motif is rarer in the Rhineland, however, and is not known at all in Raetia, so it may reflect influence from southern Gaul. The largest grave monuments of southern Upper Germany stood in the family burial grounds of isolated settlements with a high standard of living (rural villas), but seldom in an urban roadside necropolis, albeit the latter have seldom been excavated to a larger extend.

Le Bohec 1991

Y. Le Bohec, Le testament du Lingon. Collection du Centre d´Etudes Romaines et

Gallo-romaines N. S. 9 (Lyon 1991).

Le Bohec 2003

Y. Le Bohec, Inscriptions de la cite des Lingons. Inscriptions sur Pierre (Paris

2003).

Bossert 1998

M. Bossert, Die figürlichen Reliefs von Aventicum. CSIR Schweiz I, 1 (Lausanne

1998).

Bossert 1999

M. Bossert, Die figürlichen Skulpturen des Legionslagers von Vindonissa. CSIR

Schweiz I, 5 (Brugg 1999).

Bossert 2002

M. Bossert, Die figürlichen Skulpturen von Colonia Iulia Equestris. CSIR Schweiz

I, 4 (Lausanne 2002).

Bossert-Radtke 1992

C. Bossert-Radtke, Die figürlichen Rundskulpturen und Reliefs aus Augst und

Kaiseraugst. Forschungen in Augst 16 (Augst 1992).

Bridel 1976

P. Bridel, La mausolée de Wavre. Jb SGUF 59, 1976, 193-200.

Burnand 1990

Y. Burnand, Histoire de la Lorraine. Les temps anciens 2. De César à Clovis

(Nancy 1990).

CAG

Carte Archeologique de la Gaule.

Castella 1998

D. Castella, Vor den Toren der Stadt Aventicum. Zehn Jahre Archäologie auf

dem Autobahntrassee bei Avenches. Documents du Musée Romain d´Avenches (Avenches

1998).

Castella 1999

D. Castella, La nécropole gallo-romaine d´Avenches “En Chaplix”. Vol. 1 Etude

des sépultures. Vol. 2 Etude du mobilier (Lausanne 1999).

Castella 2002

D. Castella et al., Trois depots funéraires aristocratique du début du Haut-Empire

à Avenches En Chaplix. Bulletin de l´Association Pro Aventico 44, 2002, 7-102.

Castorio 2000

J. N. Castorio, Les stèles funéraires gallo-romaines de Monthureux-sur-Saône

(Voges). In: H. Walter, La sculpture d´époque Romaine dans le nord, dans

l´est des Gaules et dans les regions avoisinantes: acquis et problématiques

actuelles (Paris 2000) 109-121.

Erdmann 2004

U. Erdmann, Römische Spuren in Burgund. Ein archäologischer Reiseführer (Wiesbaden

2004).

Filtzinger 1980

Ph. Filtzinger, Hic saxa loquuntur – Hier reden die Steine. Kl. Schr. zur Kenntnis

der römischen Besetzungsgesch. Südwestdeutschlands 25 (Stuttgart 1980).

Forrer 1918

R. Forrer, Das römische Zabern – Tres Tabernae (Stuttgart 1918).

Frei-Stolba/Bielman 1996

R. Frei-Stolba/A. Bielman, Musée Romain d´Avenches. Les inscriptions. Textes,

traduction et commentaire (Lausanne 1996).

Gaubatz-Sattler 1999

A. Gaubatz-Sattler, SVMELOCENNA. Geschichte und Topographie des römischen Rottenburg

am Neckar nach den Befunden und Funden bis 1985. Forsch. u. Ber. Vor- u.

Frühgesch. Baden-Württemberg 71 (Stuttgart 1999).

Grzybek 2003

E. Grzybek, Nyon à l´époque romaine et sa lutte contre le brigandage. Genava

N. S. 50, 2002, 309-316.

Hatt 1986

J.-J. Hatt, La tombe gallo-romaine (Paris 1986).

Haug/Sixt 1914

F. Haug/G. Sixt, Die römischen Inschriften und Bildwerke Württembergs (Stuttgart

1914).

Hedinger 1996

B. Hedinger, Römisches Brandgrab mit Aschengrube in Maur-Binz. Mit einem Exkurs

zum Forschungsstand der römischen Bestattungen im Kanton Zürich. Arch. im

Kanton Zürich 1993-1994 (Zürich und Egg 1996) 103-112.

Joubeaux 1989

H. Joubeaux, Un type particulier de monuments funéraires: les “pyramidions”

des necropoles Gallo-Romaines de Dijon. Gallia 46, 1989, 213-244.

Kempchen 1995

M. Kempchen, Mythologische Themen in der Grabskulptur. Germania Inferior, Germania

Superior, Gallia Belgica und Raetia (Bonn 1995).

Kortüm 1995

K. Kortüm, PORTUS – Pforzheim. Untersuchungen zur Archäologie und Geschichte

in römischer Zeit (Sigmaringen 1995).

Landes 2002

Chr. Landes (éd.), La mort des notables en Gaule romaine. Catalogue de l´exposition

(Lattes 2002).

Langner 2002

M. Langner, Szenen aus Handwerk und Handel auf gallo-römischen Grabmälern.

In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 116, 2001, 299-356.

Légeret 2000

V. Légeret, Delémont JU, La Communance. Jb. SGUF 83, 2000, 235.

Meyer 1998

M. G. Meyer, Stuttgart-Zazenhausen. Fundber. BW 22/2, 1998, 173 f.

Meyr 2000

M. Meyr, Die Steindenkmäler des römischen Gräberfeldes Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt

(Areal Ziegelei Höfer). Ungedruckte Magisterarbeit Univ. Freiburg 2000.

Neukom 2002

Cl. Neukom, CSIR Schweiz I,7: Das übrige helvetische Gebiet. Mit einem Nachtrag

zu CSIR Schweiz III. Funde in Basel und Liestal (Basel 2002).

Noelke 1976

P. Noelke, Aeneasdarstellungen in der römischen Plastik der Rheinzone. Germania

54/2, 1976, 409-439.

Renard 1993

E. Renard, Les monuments funéraires de Nod-sur-Seine (Côte-d´Or). In: Monde

des morts, monde des vivants en Gaule rurale. Actes du Colloque ARCHEA/AGER,

Orléans 1992 (Tours 1993) 247-251.

Schaub 1992

M. Schaub, Zur Baugeschichte und Situation des Grabmonumentes beim Augster

Osttor (Grabung 1991.52). Jahresber. Augst u. Kaiseraugst 13, 1992, 77-111.

Schucany 1995

C. Schucany, Eine Grabanlage im römischen Gutshof von Biberist-Spitalhof. Arch.

Schweiz 18/4, 1995, 142-154.

Schucany 2001

C. Schucany, An elite funerary enclosure in the centre of the villa of Biberist-Spitalhof

(Switzerland) – a case study. In: J. Pearce/M. Millett/M. Struck (edd.),

Burial, Society and Context in the Roman World (Oxford 2001) 118-124.

Trumm 2002

J. Trumm, Die römerzeitliche Besiedlung am östlichen Hochrhein (50 v. Chr.

– 450 n. Chr.). Materialh. Arch. Baden-Württemberg 63 (Stuttgart 2000).

Walser 1979

G. Walser, Römische Inschriften in der Schweiz. 1. Teil: Westschweiz (Bern

1979).

Walter 2000

Aufsätze über das Mausoleum von Faverolles von S. Fevrier, G. Sauron, S. Deyts

und H. Walter in: H. Walter (ed.), La sculpture d´époque Romaine dans le

nord, dans l´est des Gaules et dans les regions avoisinantes: acquis et problematiques

actuelles. Actes du coll. int. Besançon 1998 (Paris 2000) 177-234.

Wiegels 1979

R. Wiegels, Ein römischer Grabaltar aus Niefern, Enzkreis. Fundber. Baden-Württemberg

4, 1979, 344-356.

There were marked differences between the northern and southern parts of Upper Germany, which are reflected in their separate treatment in this paper. The northern and central parts of the province will be considered here, i.e. the Limes hinterland and the military zone south along the Rhine to Strasbourg, with the tribal territories of the Treveri, Vangiones, Nemeters and Triboci. Northern grave architecture was greatly influenced by legionaries of north Italian origin, whereas the south was more strongly inspired by southern Gaul.

The

largest concentration of stone grave monuments has been found in and around

Mogontiacum/Mainz, followed at some distance by the Bad Kreuznach area (CSIR

II, 9), the border area with Gallia Belgica in the Palatinate, and other collections

in Borbetomagus/Worms (CSIR II, 10), Bingium/Bingen (CSIR II, 14), Confluentes/

Koblenz (Willer 2005, 149-163) and Argentorate/Straßburg (Forrer 1927, 85). Roadside necropolises with Italian style grave monuments

had existed in towns along the Rhine since the Tiberian period at the latest,

and numerous architectural fragments have survived by being integrated as spolia

into late

Roman fortifications. The situation in the Limes hinterland was very different. There were sometimes extensive cemeteries along

the main roads leaving the vici and some have been excavated to a greater or

lesser extent, e.g. Stettfeld, Rottweil, Bad Cannstatt, Rottenburg and Welzheim.

As a result, it is difficult to classify these as roadside necropolises (with

the exception of Nida/Frankfurt-Heddernheim, Heidelberg and Bad Cannstatt)

as they have a striking lack of funerary architecture. Even the southern cemetery

at municipium Arae Flaviae/Rottweil with c. 500 graves, largely lacked such structures (e.g.

Haug/Sixt 1914 Nr. 494; Sommer 2001). The area’s shorter history as part of

the province may be as important here as the fact that its elite, which normally

developed in the course of the 2nd century, was numerically smaller and

economically less powerful.

The

largest concentration of stone grave monuments has been found in and around

Mogontiacum/Mainz, followed at some distance by the Bad Kreuznach area (CSIR

II, 9), the border area with Gallia Belgica in the Palatinate, and other collections

in Borbetomagus/Worms (CSIR II, 10), Bingium/Bingen (CSIR II, 14), Confluentes/

Koblenz (Willer 2005, 149-163) and Argentorate/Straßburg (Forrer 1927, 85). Roadside necropolises with Italian style grave monuments

had existed in towns along the Rhine since the Tiberian period at the latest,

and numerous architectural fragments have survived by being integrated as spolia

into late

Roman fortifications. The situation in the Limes hinterland was very different. There were sometimes extensive cemeteries along

the main roads leaving the vici and some have been excavated to a greater or

lesser extent, e.g. Stettfeld, Rottweil, Bad Cannstatt, Rottenburg and Welzheim.

As a result, it is difficult to classify these as roadside necropolises (with

the exception of Nida/Frankfurt-Heddernheim, Heidelberg and Bad Cannstatt)

as they have a striking lack of funerary architecture. Even the southern cemetery

at municipium Arae Flaviae/Rottweil with c. 500 graves, largely lacked such structures (e.g.

Haug/Sixt 1914 Nr. 494; Sommer 2001). The area’s shorter history as part of

the province may be as important here as the fact that its elite, which normally

developed in the course of the 2nd century, was numerically smaller and

economically less powerful.

The oldest known Roman grave monument in Upper Germany is also the only one still

standing: the "Eichelstein", a concrete stump in the area of the Mainz citadel. This is accepted to be a

cenotaph for the general Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, a stepson of Augustus:

in other words a grave-like memorial without a burial (Drusus’ mortal remains

were buried in Rome). Several Roman historians certainly attest to the existence

of an honorary tomb for Drusus near Mainz (tumulus honorarius; monumentum Drusi) and there are various hints that might associate this with the Eichelstein.

Its sheer size is one, coupled to the choice of the traditional round tomb

form, its prominent position opposite the mouth of the Main and its combination

with a cult theatre in which regular commemorative celebrations took place.

The structure was probably started shortly after Drusus’ accidental death in

9BC, making it one of the oldest stone buildings on the Rhine.

The oldest known Roman grave monument in Upper Germany is also the only one still

standing: the "Eichelstein", a concrete stump in the area of the Mainz citadel. This is accepted to be a

cenotaph for the general Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, a stepson of Augustus:

in other words a grave-like memorial without a burial (Drusus’ mortal remains

were buried in Rome). Several Roman historians certainly attest to the existence

of an honorary tomb for Drusus near Mainz (tumulus honorarius; monumentum Drusi) and there are various hints that might associate this with the Eichelstein.

Its sheer size is one, coupled to the choice of the traditional round tomb

form, its prominent position opposite the mouth of the Main and its combination

with a cult theatre in which regular commemorative celebrations took place.

The structure was probably started shortly after Drusus’ accidental death in

9BC, making it one of the oldest stone buildings on the Rhine.

The

generally accepted reconstruction (Frenz 1985, 415 f.) would see the "Eichelstein" as at least 25m high or, more probably, as much as 100 Roman feet (c.33m), and

even today its surviving remains are still c. 22m high. Its form is comparable

with the near contemporary (post 15 BC) victory monument at La Turbie in southern

France, and a similar, if smaller, early Roman grave monument is known in Cologne

(s. Grave monuments in Lower Germany). The most important roadside necropolis

in Mogontiacum (and indeed the whole of northern Upper Germany) began to the

southeast of the Drusus Memorial, at a respectful distance from it (Witteyer/

Fasold 1995). This is the so-called "Weisenauer Gräberstrasse" which followed the Roman military road along the Rhine.

The

generally accepted reconstruction (Frenz 1985, 415 f.) would see the "Eichelstein" as at least 25m high or, more probably, as much as 100 Roman feet (c.33m), and

even today its surviving remains are still c. 22m high. Its form is comparable

with the near contemporary (post 15 BC) victory monument at La Turbie in southern

France, and a similar, if smaller, early Roman grave monument is known in Cologne

(s. Grave monuments in Lower Germany). The most important roadside necropolis

in Mogontiacum (and indeed the whole of northern Upper Germany) began to the

southeast of the Drusus Memorial, at a respectful distance from it (Witteyer/

Fasold 1995). This is the so-called "Weisenauer Gräberstrasse" which followed the Roman military road along the Rhine.

In

the first half of the 1st century AD, large stone circular tombs were also

constructed at Koblenz and Strasbourg. Only a few fragments of either survive,

but these are diagnostic in that they show the monuments’ curvature. The Koblenz tumulus had an external diameter of 9.7m. Its façade was made of pillared arcades, and its top was completed with a frieze showing

weapons and battle scenes (Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, 37; Eck/v. Hesberg 2003,

180 f), subject matter that occurs frequently on Rhenish grave monuments.

The Strasbourg tumulus was 16m in diameter and one of the largest of its type in Upper Germany (Forrer

1927, 88).

In

the first half of the 1st century AD, large stone circular tombs were also

constructed at Koblenz and Strasbourg. Only a few fragments of either survive,

but these are diagnostic in that they show the monuments’ curvature. The Koblenz tumulus had an external diameter of 9.7m. Its façade was made of pillared arcades, and its top was completed with a frieze showing

weapons and battle scenes (Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, 37; Eck/v. Hesberg 2003,

180 f), subject matter that occurs frequently on Rhenish grave monuments.

The Strasbourg tumulus was 16m in diameter and one of the largest of its type in Upper Germany (Forrer

1927, 88).

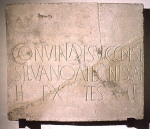

No

associated inscriptions survive, and it is thus impossible to say who commissioned

it, but Italian style stone tumuli were copied by the local population from early on. One perfect example of this

is a circular grave from Nickenich in the northernmost part of the province

(Diam: 7m Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, 36 f.; Eck/v. Hesberg 2003, 178), where

the inscription survives to give the Gallic name of the deceased: Contuinda Esucconis f(ilia) / Silvano Ategnissa(e) f(ilio) / h(eres) ex test(amento)

f(ecit).

No

associated inscriptions survive, and it is thus impossible to say who commissioned

it, but Italian style stone tumuli were copied by the local population from early on. One perfect example of this

is a circular grave from Nickenich in the northernmost part of the province

(Diam: 7m Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, 36 f.; Eck/v. Hesberg 2003, 178), where

the inscription survives to give the Gallic name of the deceased: Contuinda Esucconis f(ilia) / Silvano Ategnissa(e) f(ilio) / h(eres) ex test(amento)

f(ecit).

"Contvinda, daughter of Essuco, had this monument made for Silvanus, son of Ategnissa,

as heir according to his will" (AE 1938, 121). To judge from the name forms, these were still indigenous non-citizens.

About 40m from the Nickenich tumulus the remains of a niche monument were found (see below), which probably belonged to the same family cemetery. Its inscription does not survive, but the male deceased had themselves portrayed wearing the Roman toga, which means that they were already Roman citizens. This adoption of another Italian grave type, the relief decorated niche monument, is an indication of the degree to which "romanisation" had progressed in two to three generations, assuming that these really were monuments to the same family.

The

Nickenich tumulus is comparable to stone, circular graves at Ochtendung (Diam:. c. 15m; Ldkr.

Mayen-Koblenz) and Stromberg (Ldkr. Kreuznach). The latter had a passage (dromos) into the central burial chamber, but this had been carefully walled up after

the funeral (RiRP 568). The passage copied another Italian element (there was

one e.g. in the tomb of Augustus at Rome), but the Stromberg monument was not

designed as an accessible family vault. It is apparent, however, that the tumulus was probably constructed during the lifetime of the person who commissioned

it, possibly the villa owner. The circular tomb at Ochtendung only contained

an urn grave (for a mother and child) in a central tufa cist (RiRP 516 f.)

and so belongs to a second, larger group of tumuli, those without a dromos. A sarcophagus found next to the tambour wall shows that the associated family

burial ground remained in use into the 4th century, and stone sculptures found

nearby belonged to other memorials.

The

Nickenich tumulus is comparable to stone, circular graves at Ochtendung (Diam:. c. 15m; Ldkr.

Mayen-Koblenz) and Stromberg (Ldkr. Kreuznach). The latter had a passage (dromos) into the central burial chamber, but this had been carefully walled up after

the funeral (RiRP 568). The passage copied another Italian element (there was

one e.g. in the tomb of Augustus at Rome), but the Stromberg monument was not

designed as an accessible family vault. It is apparent, however, that the tumulus was probably constructed during the lifetime of the person who commissioned

it, possibly the villa owner. The circular tomb at Ochtendung only contained

an urn grave (for a mother and child) in a central tufa cist (RiRP 516 f.)

and so belongs to a second, larger group of tumuli, those without a dromos. A sarcophagus found next to the tambour wall shows that the associated family

burial ground remained in use into the 4th century, and stone sculptures found

nearby belonged to other memorials.

Both tumuli lay at the edge of the distribution of Belgo-Treveran barrows (Wigg 1993). As the eastern Treveran area was split between three provinces as recently as under Domitian, it is not surprising that the provincial border had no influence on their distribution.

The Limes hinterland, to the north of the Main, can be added to this distribution, as is shown by the tumuli at Weisel (Rhein-Lahn-Kreis) and Wölfersheim (Wetteraukreis) (Lindenthal/Rupp 2000).

The barrow rite appears to have revived during the 1st century AD, perhaps influenced by the classical Roman tumuli on the Rhine. For there was a gap of c. 300 years after the latest Iron Age barrows in the area. In northeast Gaul, however, the rite seems to have survived into the Late Latène period in the form of barrows used to mark ‘princely graves’. In the changed political conditions of the early Roman period is was apparently possible for a larger spread of people to use this aspect of Gallic ‘elite culture’. The Roman period barrows are, though, almost never found in the roadside necropolises of the Rhineland urban sites. Instead, they usually lie close to isolated rural settlements. The barrow distribution might thus highlight a degree of continuity in the spheres of influence of long established local clans. That said, it should not be forgotten that the barrow rite also (re)surfaced in other provinces, such as Britain, Noricum, Pannonia, Dacia and Thrace (Becker 1993), all of which share a tendency towards sumptuous grave goods. There are even some wagon graves, although this most opulent class is absent from northern Upper Germany.

Tumuli

are increasingly rare to the south of Mainz and, apart from the Strasbourg

example, the only circular tomb worth mentioning is an idiosyncratic specimen

at Mackwiller (Alsace). Here the 7.5m diameter tambour wall was surrounded

by external buttresses, which (to judge from architectural fragments) supported

columns or engaged columns. The monument may thus have been a kind of round

temple (tholos). It belonged to a villa cemetery (Hatt 1967; Landes 2002, 45) and has no apparent

connection with the central Rhenish barrows.

Tumuli

are increasingly rare to the south of Mainz and, apart from the Strasbourg

example, the only circular tomb worth mentioning is an idiosyncratic specimen

at Mackwiller (Alsace). Here the 7.5m diameter tambour wall was surrounded

by external buttresses, which (to judge from architectural fragments) supported

columns or engaged columns. The monument may thus have been a kind of round

temple (tholos). It belonged to a villa cemetery (Hatt 1967; Landes 2002, 45) and has no apparent

connection with the central Rhenish barrows.

M(arcus) Cassius M(arci) f(ilius) Quf(entina / tribu) Med(iolano) v[eteran(us)] / leg(ionis) XIIII Gem(inae) an(norum) [---] / C(aius) Cassius M(arci) f(ilius) Quf(entina / tribu) Med(iolano) frate[r mil(es)] / leg(ionis) XIIII Gem(inae) an(norum) XLV / stip(endiorum) [---] / h(ic) s(iti) sunt.

"M. Cassius, son of Marcus, of the Oufentina tribe, born in Milan, veteran of Legio XIV Gemina [---] years old, and C. Cassius, son of Marcus, of the Oufentina tribe, born in Milan, his brother, soldier in Legio XIV Gemina, 45 years old, [---] years of service, are buried here."

The inscription was found in close association with a massive (4 x 4m) stone foundation, of the type required for a mausoleum. Unusually, the upper profile only seems to have been carved on its sides but, thanks to a lack of parallels, it is not clear, what this means for the way it should be reconstructed. It is the second oldest stone grave monument in the province, after the ‘Eichelstein’ and can be dated to before 43AD (it may be Tiberian) on the basis of the grave goods and the absence of the epithets Gemina Martia Victrix, for the 14th legion. In accordance with Roman ritual, only essential grave goods, needed for the journey through the underworld, were included. The monument occupies a very prominent location, next to the legionary parade ground (campus), a site whose east side was flanked by the ‘Eichelstein’. The monument was originally 8-10 m tall and must have been costly, yet it was erected for two humble legionaries.

Only a few examples of funerary architecture

are found amongst the 180 military grave monuments (including simple stele)

known from Mainz, most of which date to the 1st century AD. Indeed soldiers

were usually just commemorated by stele. The recorded ranks of the dead never

exceed centurion (Boppert 2003, 268) and the lower ranks seem to have had

higher priorities for their savings than opulent grave monuments abroad.

This did not change in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the vast majority

of grave monuments were commissioned by civilian members of the local and

regional financial elites. Higher ranking military personnel could usually

expect their mortal remains to be repatriated and would have received an

appropriate burial at home.

That said, the reverse is true of one Imperial office holder: Zosimus, the

chief taster to the Emperor Domitian. The inscribed slab from his grave survives

in Mainz, although what form the tomb had, be it a mausoleum or otherwise,

remains unknown. It reads:

The closing formula suggests, that Zosimus really was buried at Mainz and the presence of the Emperor there during the Chattan Wars would thus date the grave titulus to the latter part of 83AD or later. An inscription with an identical text, except for the closing formula, has been found in Rome, where Zosimus’ wife and daughter erected a memorial cenotaph for him (uxor et filia monumentum posuerunt).

The

mausoleum at Heidelberg-Rohrbach probably originated as the centre of a villa

cemetery, similar to the Ingelheim monument. It was built later, however,

and probably dates to 200AD (Ludwig 2006). Such a late mausoleum is exceptional

in the northern part of the province, as pillar monuments became the most

common grave monument type from the 1st century AD, both here and in the

neighbouring territory of the Treveri. When the Rohrbach monument was found

(and subsequently destroyed) in 1896, it had deep foundations and numerous

sculptural fragments, including some from a Ganymede group (Noelke

1976). There was also a hand from a togate statue with scroll, whose very

detailed depiction of a seal ring helps to date the monument. The bearded

sandstone head of a German with a Suebian knot is hard to interpret. It could

be a reference to the Germanic roots of the civitas Sueborum Nicrensium, in whose territory the builders lived, or it might be one of the common depictions

of vanquished barbarians (Klatt 1996)?

The

mausoleum at Heidelberg-Rohrbach probably originated as the centre of a villa

cemetery, similar to the Ingelheim monument. It was built later, however,

and probably dates to 200AD (Ludwig 2006). Such a late mausoleum is exceptional

in the northern part of the province, as pillar monuments became the most

common grave monument type from the 1st century AD, both here and in the

neighbouring territory of the Treveri. When the Rohrbach monument was found

(and subsequently destroyed) in 1896, it had deep foundations and numerous

sculptural fragments, including some from a Ganymede group (Noelke

1976). There was also a hand from a togate statue with scroll, whose very

detailed depiction of a seal ring helps to date the monument. The bearded

sandstone head of a German with a Suebian knot is hard to interpret. It could

be a reference to the Germanic roots of the civitas Sueborum Nicrensium, in whose territory the builders lived, or it might be one of the common depictions

of vanquished barbarians (Klatt 1996)?

Another

group of memorials that developed in the early Roman period are monumental

stele with near life-sized, full-figure sculptures of the deceased set

in a niche, sometimes with a shell-headed concha. They developed in the

Rhineland from full-figure stele of soldiers, in contrast to Italy where

the two monument classes: stele and grave monuments, were kept separate

and

only

rarely mixed. Their ancestry also included large stele (or double stele)

with architectural frames but no images, and an example of this type is

known from Strasbourg (Forrer 1927, 275).

Another

group of memorials that developed in the early Roman period are monumental

stele with near life-sized, full-figure sculptures of the deceased set

in a niche, sometimes with a shell-headed concha. They developed in the

Rhineland from full-figure stele of soldiers, in contrast to Italy where

the two monument classes: stele and grave monuments, were kept separate

and

only

rarely mixed. Their ancestry also included large stele (or double stele)

with architectural frames but no images, and an example of this type is

known from Strasbourg (Forrer 1927, 275).

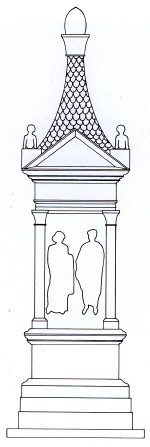

One of the earliest and best preserved examples of this type is a family

memorial from Nickenich (Kreis-Mayen-Koblenz). Originally, it probably stood

in the same villa cemetery as the tumulus discussed

above, and the three individual stele were architecturally linked with a

common base, corbel and guardian sculptures. One noteworthy side panel relief

shows two captives being led away and this may refer to some special feat

by the deceased, although the topos of the vanquished barbarian is common

on 1st century AD, Rhenish funerary reliefs (Klatt 1996).

Further

examples of this monument type have been found in Koblenz, with smaller versions

known from Mainz-Weisenau (Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, Taf. 2; Gabelmann 1987,

293), and from Cologne in neighbouring Lower Germany. The Claudian Weisenau

monument is a typological hybrid, for it has a scale-patterned roof, crowned

by a sphinx, which anticipates the later pillar monuments.

Further

examples of this monument type have been found in Koblenz, with smaller versions

known from Mainz-Weisenau (Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, Taf. 2; Gabelmann 1987,

293), and from Cologne in neighbouring Lower Germany. The Claudian Weisenau

monument is a typological hybrid, for it has a scale-patterned roof, crowned

by a sphinx, which anticipates the later pillar monuments.

This monument is a good illustration of the Mainz fashion for ‘couple reliefs’ around the mid 1st century AD. Both partners were usually depicted seated or with one seated and the other standing, and the famous large stele of an indigenous Gallic couple: Menimane and Blussus, may be the earliest example of the type (lastly: Böhme-Schönberger 2003). The local dress expresses a certain pride and cultural independence. In Italy it was particularly common for city magistrates and priests (e.g. seviri Augustales) to be depicted frontally, seated in their chairs of office (sella curulis), and this reception (and modification) of foreign ideas in Germany underlined the aspirations of local families. This monument is also the first to proclaim an economically successful life to the posterity, in Blussus’ case apparently as a Rhine shipper. Nostalgic and sometimes ostentatious scenes of the deceased’s everyday life later came to dominate the Rhineland grave monuments, especially in the Treveran area (Freigang 1997; Langner 2001).

The

Menimane and Blussus stone also differs from other stele in being double

fronted. This demanded a very specific location, either between two roads

or on a different alignment from other stele, to allow it to be seen from

two sides. A possible parallel comes from a fragment of a large stele (?)

from Ingelheim, with reliefs on two sides (CSIR II, 14 Nr. 72).

The

Menimane and Blussus stone also differs from other stele in being double

fronted. This demanded a very specific location, either between two roads

or on a different alignment from other stele, to allow it to be seen from

two sides. A possible parallel comes from a fragment of a large stele (?)

from Ingelheim, with reliefs on two sides (CSIR II, 14 Nr. 72).

The

phenomenon of double-sided relief decoration is also encountered on an architectural

fragment from a Mainz grave monument (?) of the first half of the 3rd century.

The monument had coffers on both sides and a three-sided pilaster on the

front (CSIR II, 7, 130 f.; Selzer 1988 Nr. 203). It is difficult to reconstruct

such a structure, but one possibility would be a monument split into multiple

niches, similar to the one from Nickenich.

The

phenomenon of double-sided relief decoration is also encountered on an architectural

fragment from a Mainz grave monument (?) of the first half of the 3rd century.

The monument had coffers on both sides and a three-sided pilaster on the

front (CSIR II, 7, 130 f.; Selzer 1988 Nr. 203). It is difficult to reconstruct

such a structure, but one possibility would be a monument split into multiple

niches, similar to the one from Nickenich.

One grave monument from Schweinschied (Ldkr. Bad Kreuznach) is completely unique. It can be reconstructed as a two-storey niche monument and is particularly unusual in that it was rock-cut from the local sandstone. The upper storey only survives in parts, but the upper niches had life-size reliefs of the dead, whilst the lower showed a fighting horseman in the centre, with trees and fantastic creatures to the left and right. It may have been the grave of a cavalry veteran and his family. The tomb’s setting in the landscape was also far from usual, as it neither lay along a road or on a particularly prominent site. Instead it was located in a small dell at the foot of a hill, opposite the main residence of its associated villa, which suggests that it was only visible from the farm itself (CSIR II, 9, 133-138).

Unlike

(i.a.) Raetia, funerary shrines and temples were rare in the Rhineland and

even the Claudio-Neronian so-called funerary shrine at Kruft (southern Eifel)

is only a partial member of the group (Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, 24; Eck/v.

Hesberg 2003, 171). That monument is strictly speaking a large couple stele

with architectural framing, which imitates the temple storey of a mausoleum.

It is thus possible to classify it as a variant of the niche monument and,

in many ways, such a flexible combination of architectural elements from

mausolea and stele sculptures is the really typical feature of Rhineland

grave architecture.

Unlike

(i.a.) Raetia, funerary shrines and temples were rare in the Rhineland and

even the Claudio-Neronian so-called funerary shrine at Kruft (southern Eifel)

is only a partial member of the group (Andrikopoulou-Strack 1986, 24; Eck/v.

Hesberg 2003, 171). That monument is strictly speaking a large couple stele

with architectural framing, which imitates the temple storey of a mausoleum.

It is thus possible to classify it as a variant of the niche monument and,

in many ways, such a flexible combination of architectural elements from

mausolea and stele sculptures is the really typical feature of Rhineland

grave architecture.

The great majority of 2nd and 3rd century architectural fragments come from pillars, and they are common along the "Weisenauer Gräberstraße" and the entire northern part of the province. They are rarer in the southern Limes hinterland, but not specifically so, and this may only reflect the general scarcity of grave monuments in this region, perhaps caused by different landownership patterns, rather than any striking difference in cultural habits.

The side and auxiliary reliefs fall into two common groups: mythological scenes and views of everyday life (Langner 2001). A canon had developed for both categories by the second half of the 2nd century and included scenes of the dead at table (sometimes with their family), hunting and office scenes, along with images of Lupa Romana, Hercules and Dionysian dancers (Kempchen 1995).

They

were usually densely covered with reliefs, which betrays a certain ‘horror

vacui’. This allowed scenes of a humorous genre to slip in, including the

so-called "negotiator-pillar" from Mainz, which shows a barge being loaded with barrels and sacks, with a

fallen labourer skilfully fitted into the pediment corner.

They

were usually densely covered with reliefs, which betrays a certain ‘horror

vacui’. This allowed scenes of a humorous genre to slip in, including the

so-called "negotiator-pillar" from Mainz, which shows a barge being loaded with barrels and sacks, with a

fallen labourer skilfully fitted into the pediment corner.

The

pillar at Kirchentellinsfurt near Tübingen is one of the largest of these monuments of which building stones, the

foundations, and the sandstone heads of several acroter figures have survived

(Willer

2005, 146-148). To judge from the remains, the central couple or family relief

alone must have been c. 3.5m high and, again, the pillar probably belonged

to a villa.

The

pillar at Kirchentellinsfurt near Tübingen is one of the largest of these monuments of which building stones, the

foundations, and the sandstone heads of several acroter figures have survived

(Willer

2005, 146-148). To judge from the remains, the central couple or family relief

alone must have been c. 3.5m high and, again, the pillar probably belonged

to a villa.

Here, as in other provinces, fragments of grave guardian statues, including sphinges and lions, are common finds, along with other figure groups e.g. Ganymede and Aeneas groups. These cannot be assigned to a specific type of monument, but they are known to have decorated mausolea and pillar monuments as well as the walls of grave gardens, as at Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt.

Finds

of pinecone sculptures and scale patterning from roofs can probably be classified

with confidence as decorations from the tops of pillar monuments, and an

unusual pinecone with a riding Ganymede is known from Nida/Frankfurt-Heddernheim

(Fasold 2004, 30).

Finds

of pinecone sculptures and scale patterning from roofs can probably be classified

with confidence as decorations from the tops of pillar monuments, and an

unusual pinecone with a riding Ganymede is known from Nida/Frankfurt-Heddernheim

(Fasold 2004, 30).

Altar-like grave monuments are almost unknown to the south of Mainz and an example commemorating Julius Aprilis, Julia Accepta and Julius Acceptus from Niefern near Pforzheim (Enzkreis) is currently the only one of its type in south-western Germany (Wiegels 1979). It was sawn into more than six separate spolia, which were reused as early modern grave slabs, but it was originally c.1.78m wide and c.1.1-1.3 m high. It has been reconstructed as copying east Gaulish examples (e.g. Neumagen), which is also where the people named in the inscription are statistically most likely to have come from. It thus cannot be ruled out that the tomb was commissioned by an immigrant family from east Gaul (Kortüm 1995, 153 f.; Willer 2005, 197 f.).

In 1969 the top of a grave altar was found in the Rhine near Rheinmünster-Greffern (Ldkr. Rastatt), along with four covering slabs from an enclosure wall. It is not clear whether they were all parts of the same monument, however, and it is possible, that they may actually represent the load of a barge which sank whilst carrying products from an Alsatian quarry (v. Hesberg 2005, 380; Willer 2005, 203 Nr. 211).

The cemetery at Badenheim, near Bad Kreuznach, joins Belginum/Wederath in the Hunsrück (Gallia Belgica) as an example of a necropolis that continued from the late Latène period into the 4th century AD (Böhme-Schönberger 1998; dies. 2001). Eight enclosures of up to 12 x 12m each surrounded one or two graves of the early Roman period. These were the necropolis’ most lavishly furnished graves and, like the enclosures, the richness of the grave goods betrays local-Gallic influence, albeit expressed through Roman material. However, a certain contrast is provided by the grave of a late Latène warrior, who may have been a contemporary of Caesar. For, unlike near contemporary Treveran ‘princely graves’, the burial, which was set in a large enclosure, did not contain a single Roman object. It has thus been suggested that this ‘aristocrat’ may have been in cultural and political opposition to Rome. Cemeteries with large, rectangular enclosures of varying sizes have also been found near Thür (RiRP 574), Mittelstrimmig and Urmitz, Ldkr. Mayen-Koblenz, and start in the early Roman period at the latest.

Enclosed

graves were also common in Italy, where the habit was linked to early Republican

law, and these two similar building traditions came together and continued

to develop on the Middle Rhine, despite the different ideas behind them.

One example would be the enclosure walls at the "Weisenauer Gräberstraße" (Witteyer 2002, 250), which usually surrounded family graves and had an inscription

inserted into their front or on a stele set up in front of them.

Enclosed

graves were also common in Italy, where the habit was linked to early Republican

law, and these two similar building traditions came together and continued

to develop on the Middle Rhine, despite the different ideas behind them.

One example would be the enclosure walls at the "Weisenauer Gräberstraße" (Witteyer 2002, 250), which usually surrounded family graves and had an inscription

inserted into their front or on a stele set up in front of them.

Enclosure XXX of c. 9 x 9m at Weisenau is very different, for it contained

around 100 graves with relatively uniform grave goods. The enclosure had markedly

rounded

corners,

which may have supported grave guardian sculptures, and behind it lay what

was probably the associated pyre site (ustrinum).

The number of graves far exceeds that of a normal family cemetery. As a result,

it seems justified to connect the site with a burial club (collegium funeraticum): a type of funeral insurance society, which covered the costs of burials, and

occasionally received mention on inscriptions.

A

large, similarly enclosed isolated cemetery on the Tiberiusstraße, northeast of Nida/Frankfurt-Heddernheim, may have the same explanation. This

four-sided (68 x 32 x 60 x 40m) area held 71 graves and so was slightly less

densely packed than its Weisenau counterpart, but it was clearly separated

from the street-side necropolises in the north and west of the town (Fasold

2006, 268 f).

A

large, similarly enclosed isolated cemetery on the Tiberiusstraße, northeast of Nida/Frankfurt-Heddernheim, may have the same explanation. This

four-sided (68 x 32 x 60 x 40m) area held 71 graves and so was slightly less

densely packed than its Weisenau counterpart, but it was clearly separated

from the street-side necropolises in the north and west of the town (Fasold

2006, 268 f).

The