Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium-Cologne

See this text in Foundation and structure

The oppidum Ubiorum, as the predecessor of the colonia

Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (CCAA) developed in the first decade AD. The

ara Ubiorum, an altar to the Imperial cult is attested in 9 AD while,

in 14 AD, we hear of a double legionary fortress, whose headquarters was inside

the oppidum Ubiorum. Despite place name evidence to suggest the presence

of an indigenous settlement, no archaeological traces of a local Ubian population

have been found. Cologne was founded c. 50 AD by the emperor Claudius

in honour of his wife Agrippina, who was born there in 15/16 AD and the colonia's

foundation led to a redevelopment of the site. The majority of the large building

complexes were built in the second half of the 1st century and, in 85 the

town became the capital of the newly founded province of Germania Inferior.

The rebuilding of the governor’s palace (praetorium) and the granaries

on the Rhine Island were large building projects of the 2nd century and the

city wall was rebuilt during the 3rd. In the second half of the 1st century,

workshops, which had posed a fire risk, were moved outside the city walls.

Military installations and pre-Roman settlement

The position of the double legionary fortress, attested by literary sources in the first decades AD, has so far eluded archaeological detection. It is unlikely to have lain in the area of the later colonia, however, but was probably further south, near the fort of Cologne-Alteburg.

Only fragments of the pre-existing settlement of oppidum Ubiorum have so far been identified. A tower, built of tufa blocks (‘Ubiermonument’), which is variously identified as a harbour tower or a grave monument, has been dated to 4 AD thanks to an analysis of its structural timbers. Other architectural fragments suggest the presence of large buildings such as temples in the early phases of the settlement and a stone building is known from beneath the later praetorium. The town had earth and timber defences on the north side and a V-shaped ditch on the west but it is not clear whether the orientation of the later roads had already been established. The remains of timber residential buildings have been encountered at several points in the town.

Urban structure

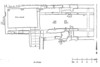

The orthogonal street grid of more than sixty insulae, covered an area of over 96.8 ha, but it is not clear if it incorporated earlier streets. The main roads were c. 32 m wide between the building frontages, with the side streets rather narrower at 20-23 m. The 3,900 m long city wall was furnished with nine gates and 19 towers and its original construction can be dated to the last third of the 1st century, around the north gate. The upper levels were rebuilt in the 3rd century.

Public buildings and infrastructure

The forum lay at the intersection of the main roads: the decumanus and cardo maximus, and occupied the space of six insulae. Towards the west, the complex ended in a monumental, 135m diameter semicircular crypto-portico (a subterranean hall), which is the postulated site of the Arae Ubiorum. At the eastern end of the square, walls and a line of columns are known, which belonged to a basilica and further large building complexes to the east of the forum, which are only partially known, may be the remains of the provincial assembly.

Facing the Rhine was a large (180m x 180m) complex which was rebuilt and altered several times between the 1st and the 4th century. The earliest period showed a marked resemblance to the principia of the Roman forts, but this was superseded after the second half of the 2nd century, by clear elements of public representational architecture. The building is interpreted as the governor’s residence and the Latin name praetorium is attested by an inscription found nearby. Numerous brick stamps testify to the involvement of the military in its construction.

The (c. 33 x 29.5 m) capitolium, whose foundations were excavated beneath the church of St.Maria im Kapitol, can be reconstructed as a peripteral podium temple. The temple lay within a walled enclosure and its interior was divided into three sections for the cult of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. It has been dated to the Flavian period (last third of the 1st century) on the basis of its masonry style.

Close to the western wall lay a (28.6 x 18.25m) temple area with two, probably Gallo-Roman, temples. Altars found in the area mention Jupiter, of whom a small statuette has also been found. Further foundations have been found in the same vicinity which may also form part of sanctuaries and date to the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

Mithraea have been found south of the cathedral and in the west of the town

(Breite Straße/Richmodisstraße).

A temple of Mars is mentioned in the literary sources, between the forum and the Rhine and further temples are likely to have existed within the town, as building inscriptions and dedications have been found.

Public baths have been found south-west of the forum (beneath the church of St.Peter and St.Caecilien), which cover the area of two insulae, although it has not yet been possible to reconstruct either their overall plan or their construction phases. The building was furnished with mosaics and dated to the second half of the 1st century AD. A further probable public bath house, found in the north of the city (insula C4), has only been partially excavated, but it too was built in the second half of the 1st century.

On the Rhine island, east of the city wall four large granaries, (up to 52m

long and 22.3m wide) have been found in a horseshoe configuration around a

courtyard, and offered over 7,000 sqm of usable floor space. A 1st century

precursor, with a large internal courtyard and a pool, has been interpreted

as an exercise yard.

Residential buildings

Our understanding of the residential buildings is dominated by the insulae in the area of the Domvorplatz (insulae H-J1). In insula H1 the occupation dates back to traces of timber buildings of the second decade AD. From the mid 1st century onwards, two timber-framed, aisled buildings were constructed on the insula, of up to 220 sqm in area. They occupied the space behind a colonnade on newly laid out plots. They have been interpreted as residential buildings of a Celtic-Germanic background, although their construction technique is Roman. It seems more likely that they were actually commercial properties, perhaps sheds but they were replaced by multi-roomed houses during the course of the later 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

The neighbouring block to the east, insula J1, was occupied by two luxurious town houses, whose plan followed Mediterranean fashion. They occupied the northern half of the block, whilst the southern half resembled insula H1. The ‘Atriumhaus’ had tabernae facing the road. The central axis of the large (1,400 sqm) house, was taken up by an entrance area, a possible atrium and a colonnaded courtyard (peristyle) at the rear. From these one could gain entrance to numerous rooms, some fairly small and the luxurious decorations included figured wall paintings. The house was built around the mid 1st century and was altered at the end of the century.

The ‘Atriumhaus's eastern neighbour is now known as the ‘House of the Dionysus Mosaic’, after the impressive find made inside it. This mimicked a rural villa and had an internal area of 3,500sqm. Over 15 rooms were grouped around a central 500sqm courtyard, which was laid out as a garden with a water feature. Apart from the one already mentioned, the building had further mosaics and was decorated with wall paintings. It was originally built in the second half of the 1st century and was rebuilt several times thereafter, whilst retaining its original ground plan. The Dionysus pavement replaced an earlier mosaic in the later 3rd century.

Mosaics have been found all over the town, testifying to fairly widespread high quality housing with luxurious fittings. The majority date to the 2nd and 3rd centuries. For the most part, workshops were situated outside the city, with potteries tending to lie to the west and south, and glass workshops in the north.

Harbour

A Roman harbour lay on the narrow strip of land between the city wall and the (now dry) arm of the Rhine in front of the Rhine island, which itself housed granaries. Oaken quays have been found, but the harbour went out of use because of silting, probably in the 3rd century.

Water supply

From around 50 AD a water supply tapped sources in the Vorgebirge, to the city's south-east. The large Eifel aqueduct which, with its branches, reached a length of almost 100km, dates to the 80s at the earliest, and possibly to the mid 2nd century. It was masonry built and mostly ran underground, but the Swisttal and the last 8 km before reaching the city wall were crossed by bridge. In the early 1st century the city's effluents were removed by open drains, but these were later replaced by masonry conduits.

Visible remains

Numerous Roman remains are visible in Cologne. The most impressive are those of the praetorium, which are conserved under the city hall, and the Roman city wall, which can still be seen at various points, including the north-west corner tower (Römerturm).

Museum

Roman finds from Cologne are on display in the Römisch-Germanische Museum. This was built over the remains of the Dionysus mosaic which is displayed in the basement.

Text: Thomas Schmidts

Select bibliography

A. Böhm/A. Bohnert, Das römische Nordtor von Köln. Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 50/2, 2003, 371-448.

M. Carroll-Spillecke, Neue vorkoloniezeitliche Siedlungsspuren in Köln. Archäologische Informationen 18/1-2, 1995, 143-152.

M. Dodt, Römische Badeanlagen in Köln. Kölner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 34, 2001, 267-331.

O. Doppelfeld, Die Ausgrabungen im Dom zu Köln. Kölner Forschungen 1 (Mainz 1980).

O. Doppelfeld, Vom unterirdischen Köln (Köln 1979).

W. Eck, Köln in römischer Zeit. Geschichte einer Stadt im Rahmen des Imperium Romanum. Geschichte der Stadt Köln 1(Köln 2004).

F. Fremersdorf, Das römische Haus mit dem Dionysos-Mosaik vor dem Südportal des Kölner Doms. (Berlin 1956).

H. Hellenkemper, Architektur als Beitrag zur Geschichte der Colonia Ara Agrippinensium. In: Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.4, 1975, 783-824.

H. Hellenkemper, Köln. In: Die Römer in Nordrhein-Westfalen (Stuttgart 1987) 459-488.

H. von Hesberg, Bauteile der frühen Kaiserzeit in Köln. Das Oppidum Ubiorum zur Zeit des Augustus. In: Festschrift G. Precht. Xantener Berichte 13 (Mainz 2002) 13-36.

H. von Hesberg, Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium: Köln, die Hauptstadt einer römischen Provinz. Kölner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 32, 1999, 637-640.

B. Irmler, Die Cryptoporticus am Forum der Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. In: Fundort Nordrhein-Westfalen (Mainz 2000) 324-327.

Köln I-III. Führer zu vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern 37-39 (Mainz 1980).

St. Neu, Zur Funktion des Kölner "Ubiermonuments". Thetis 4, 1997, 135-145.

B. Päffgen/W. Zanier, Überlegungen zur Lokalisierung von Oppidum Ubiorum und Legionslager im frühkaiserzeitlichen Köln. In: Provinzialrömische Forschungen. Festschrift Günter Ulbert (Espelkamp 1995) 111-129.

G. Precht, Baugeschichtliche Untersuchungen zum römischen Praetorium in Köln. Rheinische Ausgrabungen 14 (Köln, Bonn 1973).

G. Precht, Konstruktion und Aufbau sogenannter römischer Streifenhäuser am Beispiel von Köln (CCAA) und Xanten (CUT). In: Haus und Siedlung in den römischen Nordwestprovinzen. Grabungsbefund, Architektur und Ausstattung (Homburg/Saar 2002) 181-198.

W. Rosen/L. Wirtler, Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Köln.1. Antike und Mittelalter. Von den Anfängen bis 1396/97 (Köln 1999).

S. Seiler, Vorcoloniazeitliche Siedlungsspuren im Norden des römischen Köln. In: Genese, Struktur und Entwicklung römischer Städte. Xantener Berichte 6 (Mainz 2001) 123-134.

U. Süßenbach, Die Stadtmauer des römischen Köln (Köln 1981).

R. Thomas, Bodendenkmäler in Köln. Kölner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 32, 1999, 917-965.

G. Wolff, Das römisch-germanische Köln. Führer zu Museum und Stadt (Köln 1981).

Reports on the continuing excavations and archaeological

research on CCAA:

Kölner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte