In

In Zala County, due to the field walkings

and rescue excavations, 12 barrows were found from the Roman period (the greatest

number up till now) e.g. Söjtör and Nagykanizsa-Katonatemető. Thanks to

these works and to the additional methods such as air photographs, since the

date of the outcome of Károly Sági’s summary, the number of such find places

increased from 21 to

The number of the barrows in a cemetery is various. The greatest number was 50 till now, but one third of the mounds is standing alone. The size of these mounds is also diverse. They are now 3,5 - 25 ms in diameter, their height is between 0,2 and 3,5 ms, but some of them could have been 12 ms high. In the case of the bigger barrows (Kemenesszentpéter, Baláca), the exploitation place of the soil forming the mould can often be found nearby in the form of funnel-shaped and amphitheatrum-shaped dips.

All the forms of cremation burial can be found in them such as the cremation burial in a pit, placed on the former trampled surface or into a pit, urn burial, chest tomb, grave surrounded irregularly by stones. Besides these, more sophisticated substructures also occur, such as the circular, domed burial chamber; the rectangular, vaulted burial chambers and chambers sunk under the former trampled surface with dromos.

Both the quantity and quality of the grave goods are variable. The majority of the finds in the barrows are local-made craftmanship products, pottery vessels and bronze jewels showing provincial taste, but in the vicinity of the trade-routes and in the wealthy burial mounds, imported goods, sigillatae, glass- and bronze vessels were also placed. The differences point out that the status of the social level building these barrows wasn’t unified, because a family buried into the large barrows of Inota with wagon, horses and import goods can hardly be considered as belonging to the same rank as the people buried into the small barrows of Zalalövő with insignificant grave goods.

The appearance of the burial mounds can be dated back to the beginning of the 1st cent. AD or to the 2nd half of the 1st cent. AD throughout the Empire. The habit emerged in Rhineland, Belgium, South-England and in West-Pannonia at this time, while in East-Pannonia, their building began in the 1st half of the 2nd cent. AD. The golden age of the habit is the turn of the 1st and 2nd cent. AD, and the middle of the 2nd cent. AD in the east. From the time after the Marcomannian wars such burials are hardly known. From these later examples Becsehely-Pola was first determined as a barrow from the Severian-Age on the basis of a sigillata from Pfaffenhofen. Later it turned out that the burial place of Baláca was used till the middle of the 3rd cent. AD. In Zala County, the living was managed to be proved on the basis of sigillatae from the 3rd cent. AD, bronze vessels and a coin of Alexander Severus from Söjtör. The explanation for the discontinuity of the habit could be the change-over to inhumed burials, but it didn’t exclude the erection of the mounds as it can be seen from the examples of South-England.

One of the main problems is the exact determination of the area of occurance, since the barrows become remarkably concentrated in the mountainous and hilly regions. So on the lowlands, e.g. in East-Pannonia could have been more mounds which might have been destroyed by the intensive agricultural cultivation. It was clearly accepted for a long time that the barrows follow the bigger roads in every case. On the basis of this, Jenő Fitz and László Barkóczi thought it to be possible that people who were buried in such ways formed another ethnic group, „the people of the burial mounds” and they could have been settled in by the Romans for watching the roads. This supposition seemed to be correct until the barrow of Inota had been excavated with a wagon burial. Until then the latter was thought to indicate the aboriginal eravisci and the former was thought to reflect the newly arrivals, so the existence of the „road-watchers” became doubtful. Since then, on the basis of the excavations, it turned out that building of barrows next to the roads is characteristic of only the vicinity of the Amber Road, namely Zala and Somogy County. It can be observed in Salla and at the fields of Edde village (Somogy County). On the other hand, the barrows near Kemenesszentpéter could have belonged to the former settlement, and an approach road could have led to them from the Roman road. This kind of connection to a villa or to an inhabited place can be also noticed in Baláca, Somogyjád, Rábakovácsi and in Nemesnép, but an intensive topographical examination hasn’t been done yet.

Determinating the origin is the most problematic question, because the facts are inconsistent with each other. The rite became general among the native people, which could refer to an autochton origin. During the centuries directly before the Roman period, however, this rite didn’t exist. It could hardly be connected to the Halstatt-period which ended 400 years before the Roman conquest and neither can it be explained by the „Illyrian Renaissance” appearing under the Celtic influence because the occurrence area of the Pannonian-Illyrian and Celtic tribes is inconsistent with that of the barrows’. On the other hand, the Roman origin is also doubtful, since in spite of the fact that the habit was expanding simultaneously with the advancement of the Romanization, the barrows are missing in the vicinity of the settlements of Roman characteristics. It’s also possible that it was just a custom spreading among the native people in the province. This supposition can be proved by the wagons of the eravisci burials decorated with Dionysos scenes which can be connected to the Roman funerary cult.

Recognizing their original importance, burials were often set next to the barrows in the Late-Roman period and in the Árpádian Age.

2. Barrows appear sporadically in East-Pannonia; they were built mostly in Fejér, Tolna and Baranya County. These mounds form a different group, their rite and grave goods are almost identical with the burials without mounds in the vicinity of them. Here the ashes were often put into a wooden chest. Such burials were found in Mezőszilas which had provincial grave goods and in Szabadegyháza-Felsőcikola which showed native characteristics. The double barrows of Várpalota-Inota more or less belong to this group too, since its grave goods are similar to the other eravisci burials, but on the basis of the building of the mounds and the numerous imported goods, the find-place could be also connected to the third group.

3. This group is made up by barrows standing

alone or by twos in the vicinity of the border of Pannonia Superior and Inferior.

These mounds differ from the previous ones with their large size, their stone

buildings and finds too. Encircling walls, graveyards, corridors, painting and

covering with stucco are the general characteristics of this group. They are

concentrated along the Amber Road, the most eastern example of this type was

excavated in Baláca-Likasdomb. The two barrows of Kemenesszentpéter are specific

find-places of the group. Under the I. barrow, a burial chamber with a passage

was excavated. The room was covered with terrazzo floor, the main burial could

have been under this floor which was demolished by robbers most probably in

the Late Roman period. The 5,88 ms long and 1,9 ms wide hall had a same floor

and it was closed with a two-leaved door. Both its walls and vault were plastered

with red striped painting with flower motif such as its chamber. Signs referring

to the inner tidying of the chamber were also found which makes the find place

all the more valuable. Two niches were deepened into the northern wall of the

chamber. On the basis of the painting of the walls and the holes in the floor,

an armchair and a table with three legs could have been placed there. The barrows

themselves were in rectangular graveyards with 25-40 ms long sides. 11 more

mounds were erected here, which could refer to the long term use of the cemetery,

however newer barrows were built here in comparison with Baláca where grave-altars

were built to the barrow.

The cemetery that lies on the confines of the boii region contains barrows with different size in rows pointing to the west and east. The originally circular-shaped mounds moved in the direction of north and south due to the moving of the hillside. Within the rows, seven groups can be separated which could have been built at the same time, but referred to burials with different social status. Within these groups, the mounds could stand in lines or irregularly. Their form and size are varied, but we can’t infer the richness of the deceased from it, because goods with better quality were often found in smaller barrows. The graves could have been built from the ground of the adjoining land, but fluvial gravels, which could have been carried from the Zala on purpose, were also found in some of them.

Generally, the burial rite was cremation in this cemetery too. There must have been an ustrinum, because nothing referred to the cremation at the graves, but the ustrinum hasn’t been found. The charcoal marks burned through, however, could refer to the fact that in the case of some mounds the funeral-piles were made at the place, but the supposition was also held that these are the remains of funeral fires with cultic function since the burned strata were only 2-3 cms thin. This supposition is refuted by an Austrian observation which says that lamps weren’t placed to that graves where funeral fires were made, but these barrows in Zalalövő contained such lamps.

The bustum was orientated north and south in contradiction with the Roman tradition. The graves were usually placed in the middle of the mound either the dead was burnt at the place or not.

After the rite had been carried out at the common cremation

pit, the remains of the cremation were mostly buried in a pit. Some of the

dead were put into chest tombs from bricks or tegulae and two urn burials were excavated

as well.

Into the most wealthy barrow (No.9.), numerous grave-goods connected to magical belief were put: an obolus into the mouth of the deceased, a beaker, a vessel, a large bowl to the dead’s left side, a beaker to the right side of his head and a lid. These finds showed secondary burning marks, so they had been put into the grave before the funeral-pyre was lit. After the cremation other goods were placed into the grave: an iron knife in a beaker, a lamp and after the pit had been covered with a plank, they built a tube from imbrex into the mound, so the dead could keep in touch with the outside world. Remains of clothes hadn’t been found in Zalalövő and wooden chest aren’t known either, so the burned bones could have been put into the grave in a sack or in a veil.

The ceramics of the cemetery contained provincial wheel-made

vessels from local workshops. Only one urn shows Celtic influence and the

using of wavy line decoration could be traced back to

On the basis of the ceramics and a coin of Vespasian, the barrows could have been erected between the end of the 1st cent. AD, the beginning of the 2nd cent. AD and the end of the 2nd cent. AD, but it’s possible that such burials were started to be built in the middle of the 1st cent. AD, and these earlier mounds had been destroyed.

The barrow of Zalalövő belonged to Salla, the Roman

settlement, which makes this find-place special among the burial mounds in

Hungary.

Mezőszilas

Notes of the finds remained from altogether 11 graves. The 47 ceramics among them are really mixed, 8 from them can be traced back to Celtic forms but the influence of the Po-region is stronger. The Drag. 37. bowl from the VIIIth grave and the stamped pottery with leaves from the IInd and IIIrd graves are characteristic products of the local pottery. In the IIIrd grave, a plate with RESPECTUS F stamp was found, which is also known from Aquincum. TS-imitations with relief decoration mainly from Aquincum and one from Siscia also occur. The red, flowerpot-shaped beakers could be imported goods.

The few glass-vessels came unambiguously from Aquileia. On the basis of

the finds and a Domitian-coin found as a stray find, the graves could be dated

back between the end of the 1st cent. AD and the middle of the 2nd cent. AD.

Apart from the coin mentioned above, locally made bronze fibulae, mounts, a pitcher, a jug, a patera with umbo and a bronze mirror of eravisci type also prove the date.

Significant layers of ashes can be observed in the mounds which could have been the remains of the burning at the place or the remains of the funeral-pile from the common cremation pit could have been carried there. Under these layers, bronze- and ironmounts of former wooden chests were found and also two grey bowls overlaid each other with the ashes in it. The placement of the ashes into wooden chests was general in East-Pannonia.

The barrows of Mezőszilas represent a population that carried out industrial activity and responded to the influence of Italia and Gallia better than the people who erected the other barrows in the contemporary County Fejér (e.g. Pátka). This might be due to the fact that the section of Sopianae-Floriana road between Dég and Tác passed through this area, but finds clearly show the eravisci traditions in the giving of grave-goods this way too.

Baláca

The barrow was not built for the earliest owner of the villa, but for the possessor from the ordo equester (according to the inscriptions) and his family who obtained the land in the 2nd half of the 2nd cent. AD. The animal burials (a dog and a horse) with bustum, the fragments of inscriptions and the pottery- and glass finds could help to state the date precisely.

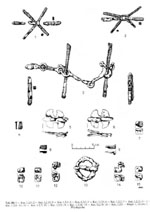

The bridles with iron- and bronze mounts were the first finds of the region and this horse equipment dates back to the the period of Hadrian and Antonine Pius on the basis of similar pieces from Inota. But this one and the other animal burial with bustum seem to have belonged to the graveyard entombing the mortal remains of the former owner as well, surrounded by a ditch and perhaps covered with a smaller mound. On the basis of the inscriptions, Jenő Fitz came to the conclusion that the family who erected the barrow obtained the villa in the middle of the 2nd cent. AD and they could have lived there till 260 AD throughout four generations. It is proved by the pottery and glass finds, and the dates are in conformity with the building history of the villa.

After the destruction had reached the eastern part of the building, it was rebuilt in the end of the 2nd cent. AD and in the beginning of the 3rd cent. AD. It was also enlarged in the beginning of the 200’s. In the middle of the 3rd cent. AD, a disorder occured, the heating of the northern corridor in the main building was stopped and a coin-treasure which had a closing coin from 259 AD was hidden into the heating-flue. The family lived there up to that time and built the tumulus could have left the villa once and for all.

On the basis of the inscriptions, the family came from the city of Tolentinum from Central Italia. Titus Claudius who is thought to be the head of the family was a duumvir in Urbs Salvia, his descendants held offices in Tolentinum and in the neighbouring towns, as well as in Savaria and Carnuntum.

The building devices of the grave also show the Italian origin of the family. During the excavation of the barrow 1300 trimmed stones were found, 800 fragments of yellowish-white arenaceous limestone from them came from altars and the portal, but the architectonic organs were red sandstones from the Balaton-uplands. 9 grave-altars and 13 „altar-imitations”, which could have been built into the walls, were reconstructed. 7 „real” altars were placed on the opposite walls of the tumulus and the others were irregularly around the tambur-wall. The altars standing on the two sides of the entrance of the dromos are the oldest ones, the others were made on the basis of them.

The following texts were reconstructed on the basis of the inscriptions on the grave-altars (only one third of the original text remained, so these elucidations are still subject to considerable change):

1. [Ti(berio) Claud(io) Ti(berii) f(ilio)] Apri/

[eq(uiti) R(omano) dec(urioni)

c]oloniae Cl(audiae) S(avariae)/

[om(nibus) hon(oribus) per]funct(o) / [col(oniae)

Sept(imiae) Ca]rn(unti) / [---?]

2. Ti(berio) C[l(audio) Ti(berii) f(ilio)

V]al[eri]o [dom]o) / To[lent(ino) e]q(uite) [R(omano

praef(ecto) c(o)h]o(rtis)

[I?] / Dalma[t(arum) ?d(ecurioni) c(oloniarum) Tolenti]ni/

P[iceni? II v(iro) c(oloniae)

Fale]rii

3. Ti(berio) [Cl(audio) Ti(berii) f(ilio) ---dom]o/

T[olent(ino) eq(uiti) R(omano) d]uo /

[viro Urbi]s Sa[lviae / Ti(berii)

Cl(audii) Ti(berii) f]i(lii) Avono / Vi[ctorinus---] avo

4. T[i(berio)] Cl(audio) Ti(berii) f(ilio) [V]el[ina

(tribu)]/ Caeci[l]ia[n]o/

R[e]to[n]ia[e] Av[ae / Ti(berius)

C]l(audius) Ti(berius) f(ilius) [A]vo[no] /f(ilius)

[p(osuit)]

5. [Ti(berio) Cl(audio) Ti(berii) f(ilio) V]icto(rino)

or ri e(quiti) R(omano) et]

Decu[mi]ae A[---]e co(niugi)

/ [Ti(berius)] C[l(audius)] Pat[i]n[us] fi(lius)

6. [Ti(berio)] C[laudio Ti(berii) / f(ilio) Pat[ino---

/ I]un(iae) A[---]e/ [---

7. Va[ler]ia[e] Ti(berii)/ fi(liae) [---]

8. C[laudiae Ti(berii)]/ f(iliae) R[etoniae or

–omanae)

9. Va[leria]e C(ai) [f(iliae)] / Cae[ciliae---]

/f[---]

The rectangle-shaped altars stood at the highest row of the three-stepped foundation, and the tambur wall of 1, 40 ms heigh was closed by a cornice. An attic from rounded-cornered blocks was placed on that. The whole height of the front must have been 2, 90 ms compared to the ancient level. The barrow could have been 10-12 ms heigh. A pine-cone shaped carved work standing on a circular slab could have decorated the top of the mound.

Iov[i] C[onse]r[va]t[o]ri [et / Dis] De[abusqu]e [om]ni[bus]The barrow was built in a graveyard surrounded by a wall. The gate of the graveyard and the corners of it were decorated with two pyramid-shaped works and a cylindrical carved one.

The barrow of Baláca is prominent among the find-places of

Pannonia and the neighbouring provinces with its large size, the extremely

rich and solid works and numerous inscriptions.

The 1. barrow is

26,6 – 31,6 ms in diameter and 1,5 ms high. In the middle of the mound a grave

came to light with the remains of the funeral-pile above it. North from it some

post holes were found which could have belonged to the structure of the grave

and they could have held the contingent decorations of the mound’s top; in the

southern part a pit (

The

main grave pit was rectangle-shaped with rounded corners (

The

main grave pit was rectangle-shaped with rounded corners (

Apart

from the skeleton, the iron mounts of the bridle also can be seen in the grave

of the riding horse which was orientated east and west. The cremation pit lay

North-East from this pit. Bronze mounts of a chest, burned bones of birds and

pigs came to light from this. Those grave-goods which were burned with the dead

or thrown later into the fire as offerings (metal artifacts, animal bones) can

be clearly separated from those those objects which were placed next to the

dead only at the funeral (most part of the pottery).

Apart

from the skeleton, the iron mounts of the bridle also can be seen in the grave

of the riding horse which was orientated east and west. The cremation pit lay

North-East from this pit. Bronze mounts of a chest, burned bones of birds and

pigs came to light from this. Those grave-goods which were burned with the dead

or thrown later into the fire as offerings (metal artifacts, animal bones) can

be clearly separated from those those objects which were placed next to the

dead only at the funeral (most part of the pottery).

There were three

graves in the mound. The first one contained the remains of the owner. In the

pit (

In the second grave, a harnessed riding horse, an iron spearhead, a shield with iron boss, a bronze jug, iron strigilis and iron pieces of a wagon were found, and in the third grave there were remains of harnessed workhorses.

Into this grave, eight skeleton burials were dug later, some of which could be from the Early-Árpádian Age.

The

funerary monuments marked by stelae presumably didn’t differ fundamentally

from the simple graveyards that were marked in some other, incomprehensible

ways. Delimiting the graves from each other is really hard because of the

destruction and disturbance of the surface layers.

The

funerary monuments marked by stelae presumably didn’t differ fundamentally

from the simple graveyards that were marked in some other, incomprehensible

ways. Delimiting the graves from each other is really hard because of the

destruction and disturbance of the surface layers.

In

1938 Lajos Nagy excavated a graveyard in the 3rd district, in the Daru Street.

The wall (

In

1938 Lajos Nagy excavated a graveyard in the 3rd district, in the Daru Street.

The wall (

Memoriae Q………oni mil(iti) coh(ortis) (milliariae)

nov(a)e Suror(um) stip(endiorum) III

vix(it) ann(os) XX Aelia Marcia mater filio

dulcissimo Appollonia soros eius faciendum curaverunt

[et Aelia

Lubrica quassa levis fragilis bona vel mala

fallax

vita data est homini- non certo limite cretae

per varios casus tenuato stamine pendes

Vivito mortalis dum dumdant tibi tempora Parc(a)e

seu te rura tenent urbes seu castra vel (a)equor

flores ama Veneris Cereris bona munera carpe

et fuisti (?) larga et pinguina dona Minervae

candida vita cole iustissima mente serenus

iam puer et iu(v)enis iam vir et fessus ab

annis

talis eris tumulo superumque oblitus honores

The

name of the dead is deficient, it started with Q. He served for three years

in the cohors milliaria nova Surorum

and he died at the age of 20. The grave was erected by his mother, Aelia Marcia

and his sister, Apollonia. The burial can be dated back to the first decades

of the 3rd cent. AD. The second sarcophagus had a place for inscriptions, but

it’s not completed. On the two sides of it, two genii can be seen resting on torches.

This sarcophagus stood so tightly behind the other one that the inscription

could not have been seen in any way, this might be be the explanation for the

fact that the foreside of it was left empty. A memory-board could have been

put into the wall of the graveyard but it wasn’t found. On the basis of the

difference between the styles of the two sarcophagi, they could have been made

in two different workshops. It’s likely that a Syrian family was buried into

this graveyard with temporal differences. The numbers of the dead are not known

because of the grave plunderings. In the southern part of Budaújlak graveyards

were found recently. These graveyards belonged to the big cemetery of Bécsi

Road. Three graveyards with built walls came into light during a rescue excavation;

two are rectangular-shaped and one is circular. The inner part of the I.

rectangular, closed graveyard is 3 x

The

name of the dead is deficient, it started with Q. He served for three years

in the cohors milliaria nova Surorum

and he died at the age of 20. The grave was erected by his mother, Aelia Marcia

and his sister, Apollonia. The burial can be dated back to the first decades

of the 3rd cent. AD. The second sarcophagus had a place for inscriptions, but

it’s not completed. On the two sides of it, two genii can be seen resting on torches.

This sarcophagus stood so tightly behind the other one that the inscription

could not have been seen in any way, this might be be the explanation for the

fact that the foreside of it was left empty. A memory-board could have been

put into the wall of the graveyard but it wasn’t found. On the basis of the

difference between the styles of the two sarcophagi, they could have been made

in two different workshops. It’s likely that a Syrian family was buried into

this graveyard with temporal differences. The numbers of the dead are not known

because of the grave plunderings. In the southern part of Budaújlak graveyards

were found recently. These graveyards belonged to the big cemetery of Bécsi

Road. Three graveyards with built walls came into light during a rescue excavation;

two are rectangular-shaped and one is circular. The inner part of the I.

rectangular, closed graveyard is 3 x . A gravestone was put into the eastern wall. A cremation burial was uncovered which was orientated in the direction of north and south and had three jugs, a pot, a Raetian beaker, a lamp with the inscription of CASS/, two globular amphorae and a coin of Diva Faustina from 141-161 AD as grave goods. On the gravestone, Romulus and Remus, the wolves and two shepherds can be seen. The legend itself was represented on numerous Pannonian gravestones, but the scene with sheperds is characteristic only of Aquincum. Most of the gravestones depicting Romulus and Remus were ordered by Celtic families in Pannonia. On the basis of the coin and the depiction of the gravestone, the burial can be dated back to the middle of the 2nd cent. AD.

There was no stele found in the other rectangular graveyard with No.III., only a 140-cm-wide entrance came into light on the eastern side. a glass bottle with band handle, a TS bowl, a black plate, a glazed vessel with three handles and a bowl of Drag.37 form were found in the grave as grave goods. The graveyard No.II. is circular-shaped and was surrounded by a wall which was 3,30 ms in diameter. Inside of the fence, wooden- or stucco decoration or rows of niches could be placed, but only the stone foundation of them set out radially to the centre remained. There were two disturbed cremation burials in the grave where two jugs and some fragments of pottery were found. The graveyards were rebuilt and today they can be visited in the courtyard of the building because of which the excavation was carried out. In the cremation cemetery of Keszthely-Újmajor a graveyard or a building was surrounded by a 25m x 3m wall and it was divided by smaller rooms along its longitudinal side. Two grave-inscriptions were found here which could have been built into the wall or to a higher building as well. The other form of the graveyards is when pillars carved from one stone were placed on the corners. Between the pillars, a slab or a wall formed the fence, on the foreside, the inscription was placed between the butt piers. For

lack of the complete collection we only know that this kind of funerary monument

became general in the eastern part of the province in the 2nd-3rd cent. AD.

One of the first excavations where such graveyards came to light was carried

out by Sándor Garády in Testvérhegyi dűlő, next to the Leopold-brickworks

of Óbuda in 1936. Three buildings (two of them were dwelling places, the third

had other functions) and a graveyard east from one of the domestic structures

were dug up. A stone with inscription and a full-length statue which could

have represented the dead person and was placed on the top of the facade formed

the front of the enclosing. Pillars carved from one stone and decorated with

pineae were put at the corners.

For

lack of the complete collection we only know that this kind of funerary monument

became general in the eastern part of the province in the 2nd-3rd cent. AD.

One of the first excavations where such graveyards came to light was carried

out by Sándor Garády in Testvérhegyi dűlő, next to the Leopold-brickworks

of Óbuda in 1936. Three buildings (two of them were dwelling places, the third

had other functions) and a graveyard east from one of the domestic structures

were dug up. A stone with inscription and a full-length statue which could

have represented the dead person and was placed on the top of the facade formed

the front of the enclosing. Pillars carved from one stone and decorated with

pineae were put at the corners.

The inscription of the grave was:

D(is) M(anibus)Bithin[a]e Sever[a]e qui

vixit ann[os] sexaginta Claudi[us]

Ursus f[ilius] Maxima et

Maximina fili[ae] matri

pientissime

faciendum cur[averunt]

The reconstruction of the funerary monuments similar to the aediculae is nearly certain. A good example fo this is the building recontsructed on the basis of a relief and grave-inscription from the end of the 2nd cent. AD. and the beginning of the 3rd cent. AD. which were built into the Late-Roman grave of Gyermel. On the large relief, a bearded man wearing a toga and two women in native costumes can be seen. One of the women is wearing a veil; there are winged brooches on their shoulders and they’ve got necklaces with medallions. The relief represents a Romanized local family. This slab could have belonged to a bigger aedicula. The inscription was made for Aurelius Respectus and his wife, Sisiuna, his sons, his 18-year-old daughter, Sisiu and for one of their relatives called Dervonia. Two half-length male portraits in medaillons surround the the inscription from the two sides. The reconstruction of the funerary monument can be defined on the basis of the Ennius-monument in Šempeter. The large relief could be the rearside of a columned, opened niche and the inscription could have been set in the facade of the high base.

In Carnuntum, a sanctuary of a templum in antis type standing on a podium was reconstructed; and on the basis

of fragments found in Gorsium, a drawn reconstruction of a funerary monument

similar to the Large Mausoleum of Aquileia was made.

Bónis, É.B. , ’A noricum-

pannoniai halomsíros temetkezés korhatározásának kérdése- A Fejér megyei tumulusok

jellegzetes emlékanyaga’ Archaeologiai

Értesítő 102 (1975) 244- 250.

Brumat Dellasorte, 2005:

Brumat Dellasorte, G., Aquileia

and San Canzian. Venezia 2005.

Csizmadia- Németh, 1997:

Csizmadia,

G.- Németh, P. G., ’Roman Barrows in County Somogy’ Balácai Közlemények

Erdélyi, G., A római kőfaragás és kőszobrászat

Magyarországon. Budapest 1974.

Ertel, 1996:

Ertel, C. ’Altar- und Architekturfragmente

vom Tumulusgrab bei Baláca’ Balácai Közlemények 4 (1996) 73- 199.

Ertel, 1997:

Ertel, C., ’Der Tumulus von Baláca- ein Grabbau Italischen Charakters’ Balácai Közlemények 5 (1997) 29- 43.

Ertel, C., ’Konstruktive Bauteile

von Römischen Grabbauten im Aquincum Museum’ Budapest Régiségei 33 (1999) 197- 241.

Ertel, 2001:

Ertel, C., ’Spolien aus der

Mauer des spätrömischen Legionslager von Aquincum. Fragmente von Grabältaren

ohne Inschrift im Aquincum Museum’ Budapest

Régiségei 34 (2001) 79- 104.

Facsády, 1999:

Facsády, A.R., ’Római sírkertek

Budaújlak déli részén’ Budapest Régiségei 33 (1999) 279- 290.

Fitz, 2003:

Fitz, J., Gorsium- Herculia. Székesfehérvár 2003.

Fitz, 1996:

Fitz, J., ’A balácai tumulus feliratai’

Balácai Közlemények 4 (1996) 199-

237.

Gerevich, 1973:

Gerevich, L.(ed.), Budapest

története I. Budapest 1973.

Intercisa I:

Barkóczi, L.- Erdélyi, G.- Ferenczy,

E.- Fülep, F.- Nemeskéri, J.- Alföldi, M.R. – Sági, K., Intercisa

(Dunapentele- Sztálinváros története a római korban) I. Budapest 1954.

Kiss, 1957:

Kiss, Á., ’A mezőszilasi császárkori

halomsírok’ Archaeologiai Értesítő 84 (1957)

40- 53.

Kuzsinszky, 1906:

Kuzsinszky, B., ’Az aquincumi múzeum

kőemlékeinek negyedik sorozata’ Budapest Régiségei 9 (1906) 34- 72.

Mócsy- Szentléleky, 1971:

Mócsy, A.- Szentléleky, T., Die

Römischen Steindenkmäler von Savaria. 1971.

MRE:

Visy, Zs. (ed.), Magyar régészet az ezredfordulón. Budapest

2003.

Müller, 1971:

Müller, R., ’A zalalövői császárkori

tumulusok’ Archaeologiai Értesítő 98(1971) 3-

24.

Nagy, 1939:

Nagy, L., ’A szír és kisázsiai

vonatkozású emlékek a Duna középfolyása mentén’ Archaeologiai Értesítő 52(1939) 115-

148.

Nagy, 1950:

Nagy, T., ’Római kőemlékek

Transaquincum területéről’ Budapest Régiségei 15 (1950) 357- 388.

Palágyi, 1990:

Palágyi, S.K. (ed.), Noricum-

pannoniai halomsírok. Veszprém 1990.

Palágyi- Nagy, 2000:

Palágyi, S.K.- Nagy, L., Római

kori halomsírok a Dunántúlon. Veszprém 2000.

Palágyi, 1982:

Palágyi, S. K., ’Die Römischen

Hügelgräber von Inota’ Alba Regia XIX (1982) 7- 95.

Palágyi, 1996:

Palágyi, S. K., ’A balácai római

kori halomsír kutatása’ Balácai Közlemények 4 (1996) 7- 73.

Palágyi, 1997:

Palágyi, S. K., ’Hügelgräber mit Dromos- Dromos-ähnlicher Vorkammer in Nord- Pannonien (Ungarn)’ Balácai Közlemények 5 (1997) 11- 29.

PRK:

Mócsy, A.- Fitz, J. (eds.), Pannonia régészeti kézikönyve. Budapest

1990.