The number of sanctuaries connected to the religion of the local population is very low, which is of course due to the fact that the native gods are hardly known, as the native gods were relegated to the background when Pannonia was founded and they lived on becoming one with certain Roman gods (Silvanus). We can draw conclusions regarding the native beliefs only from the finds of the Roman period.

Not more than three sanctuaries are remarkable:

This is a Celtic sanctuary. In this area surface collection and rescue excavation were carried out between 1969 and 1971 in connection with the construction of the M7 motorway. The find place was a Celtic centre in the northeast of Transdanubia, in the vicinity of Lake Velencei. A sacred region was uncovered with ditches around it, a locus consecrati where offertories were made. In case of danger, or festive occasions, human and animal sacrifices were made at this place. The ditches surrounding the sanctuary and running in parallel with each oher 42 kms long can be seen to the northeast and to the southwest and at their southwestern end the area of the sanctuary was closed with transversal ditches. The northeastern end of the area was unfortunately ruined. The sanctuary is 300 ms away from Lake Velencei and 20 ms away from a stream-source. In the vicinity of the sanctuary smaller pits, pit-systems with human and animal remains were found (the pits are about 40 cms wide and 40-50 cms deep, circular and semicircular shaped) from different periods. The pits were prepared for various ceremonies. The foundation of the sanctuary can be dated to the La Tène period, but its living on in the Roman period can be also proved because remains of a sacrificed dog lying on a Roman brick were found in one of the pits. On the basis of this, such livings on can be assumed in other areas of Celtic sanctuaries as well, at least in the beginning of the Roman rule, in the first half of the 1st cent. AD.

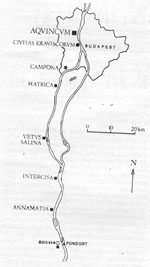

The second sanctuary is Pfaffenberg of Carnuntum. We don’t want to treat the subject in detail, because it lies outside our frontiers, so it can be connected to the Austrian research. It is, however, important to mention because of its relations with the sanctuary of Gellérthegy.

It was built to east from Carnuntum, next to the legio camp and to the civic town. Rescue excavations were done by W. Jobst between 1970 and 1985 in connection with a mine-sinking. The finds found here were set in a new Museum in Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. Pfaffenberg has Celtic antecedents which can be connected to the boius tribe. The building of the sanctuary has already begun in the 1st cent. AD. The buildings were founded during the rule of Hadrian who gave the municipium rank to Carnuntum. Most of the inscriptions can be dated between to the rule of Antonine Pius and Septimius Severus. The cult-activities lived on till the end of the first tetrach, the complete destruction took place in the end of the 4th cent. AD., when the Christians destroyed it. This sacred place contained 2 small Iupiter-temples (I. and III. temple) and a temple with 3 naves, which was the temple of the Capitolian Triad (II. temple). Apart from these, a small amphitheatrum was built to the complex which served as a ritual theater in connection with the cult. During the 4th cent. AD., several monuments (small and big-sized ones) were erected. A group of finds can be found in the northwestern part of the temple-area which played an important role in the emperor worship (Ara Augustorum). Numerous column monuments and their foundations can be found here. The altars were dedicated to Iupiter Optimus Maximus K(…) and the date of the dedication is always 11th of June. Altars of Pfaffenberg were erected mostly by Roman citizens and veterans who settled down in the canabae legionis and whose community was called as cives Romani Consistentes Carnunti intra leugam. The rites connected to the cult were carried out by a special group of priests, the magistri montis.

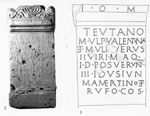

The third and the most significant sanctuary is the sanctuary of Iupiter Optimus Maximus Teutanus. Altar-stones dedicated to Teutanus are known from many places in Pannonia. Two stones are known from Aquincum where the find place is identical with the original place of their erection. Numerous altar-stones were found in Bölcske where they were secondarily built into the fort’s wall. A stone from Kiskunlacháza (from the Barbaricum) and from Székesfehérvár can be connected to this cult. The primary question was the determination of the place where the altar-stones dedicated to Teutanus were originally set. This place could have been the Gellérthegy.

One of the altars in Aquincum was found in Szépvölgyi Road in 1953 by Tibor Nagy who uncovered a foundation of a Roman building there. Later he determined the building as the governor’s villa without any proofs. After examining the documentation of the excavation Endre Tóth arrived at the conclusion that this building couldn’t have been a villa. A small sanctuary was set axial to the building, a foundation of a column and a statue of Iupiter standing on the column were found in this sanctuary. Unfortunately, the find remained in fragments. Only the upper line of the inscription is known, and the whole inscription cannot be reconstruated. The legible line: I. O. M. / Teutano / Conservatori

The Szépvölgyi Road lies in the southern part of Aquincum. The object itself lies 1400 ms from the legio camp, so it was placed into military territory. Above the Danube many small aediculae, opened chapels and a podium temple standing in the centre were found inside of a region defended by stone-fence. The speciality of the sanctuary-centre in Aquincum is a statue of Iupiter placed on a column, but only its torso remained. The god holds a scaeptum and an eagle can be seen at his feet.

The other altar dedicated to I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo) T(…) was found in 1888 on the southern terrace of the Gellérthegy. The hill wasn’t built in till the 2nd half of the 19th cent. AD., then the building of the Citadella destroyed the upper plateau of the hill, so excavations cannot be carried out here. Only one note remained regarding this building, on the basis of it a rectangular building was found. Many excavations were carried out on the hill in the 20th cent. AD. when a Celtic oppidum connected to the eravisci was uncovered and the researchers established that after the Roman conquest the place was given up in the 1st half of the 1st cent. AD. Buildings referring to a sanctuary-area from the Roman period hadn’t been found and it’s questionable whether we should search for a sanctuary from stone on the terrace of the hill.

The oppidum of the Celtic eravisci lied on the Gellérthegy during the Roman conquest, the oppidum was surrrounded by walls and earthwork and it was the centre of the eravisci tribe. According to Klára Póczy they could have paid their respects to their main god, Teutanus "the valiant in battle" here. This sanctuary stood in the centre of Budapest, in the place of the present Citadella. After the Roman conquest, the local god could have been identified with Iupiter, the main god of the Romans because of the similar character and the same power they posessed. So after it they called him Iupiter Optimus Maximus Teutanus and represented him as Iupiter.

On the basis of the altar-stones found in Bölcske and according to Endre Tóth, the supposition of Klára Póczy that we have to reckon with a native sanctuary and cult living on in the Roman period could be called in doubt. And there could not be found a native god in the shape of Teutanus who would have been worshiped later on as Iupiter. But our characterization of the native gods above is contrary to this!

In

the last few years, altar-stones dedicated to Teutanus were brought into light

by scuba divers from the Danube near Bölcske. The research in Bölcske

is connected to Sándor Soproni, according to his studies these altar-stones

were used secondarily during the building of the fort from the 4th cent. AD.

50 different stones have been found up to now. These stones were found on the

surface of the ruins and around the wall of the fort. The altar-stones used

as building materials could have been transported by water to Bölcske.

Soproni diveded the stones found here into two groups. The first group contains

large, more decorative altar-stones, sometimes decorated with reliefs on their

sides; these stones were dedicated by office-holders of Aquincum, mainly by

the duumviri to Iupiter Optimus Maximus Teutanus and to the salvation

of the emperor and of the civitas Eraviscorum. The date of all the dedications

is ante diem III idus Iunias, the 11th of June. The following

11 inscriptions can be classified into this group:

In

the last few years, altar-stones dedicated to Teutanus were brought into light

by scuba divers from the Danube near Bölcske. The research in Bölcske

is connected to Sándor Soproni, according to his studies these altar-stones

were used secondarily during the building of the fort from the 4th cent. AD.

50 different stones have been found up to now. These stones were found on the

surface of the ruins and around the wall of the fort. The altar-stones used

as building materials could have been transported by water to Bölcske.

Soproni diveded the stones found here into two groups. The first group contains

large, more decorative altar-stones, sometimes decorated with reliefs on their

sides; these stones were dedicated by office-holders of Aquincum, mainly by

the duumviri to Iupiter Optimus Maximus Teutanus and to the salvation

of the emperor and of the civitas Eraviscorum. The date of all the dedications

is ante diem III idus Iunias, the 11th of June. The following

11 inscriptions can be classified into this group:

The duumviri of the municipium of

Aquincum dedicated the altar-stone to I.O.M. Teutanus on 11th of June in 182 AD.

The duumviri dedicated the altar-stone to I.O.M. Teutanus between 222 and 235 AD. The name of Alexander Severus was erased from the inscription.

Marcus Aurelius Maturus and Marcus Aurelius Valens duumviri dedicated it to I.O.M. Teutanus and to all the gods and goddesses on 11th of June in 251 AD. The name of Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus were erased.

M(arcus) Aurel(ius) Polydeucus and M(arcus) Aurel(ius) Cimes from the ordo equester erected the altar on 11th of June in 284 AD. and dedicated to [I.] O. [M.] Teutanus in the time of Carinus and Numerianus.

Antoninus Castor duumvir who held the office of flamen and aedilis erected it on 11th of June in 250 AD. The name and titularity of Decius were erased.

T(itus) Fl(avius) […]ius augur from the ordo equester and M(arcus) Aurel(ius) Sabinianus quinquennalis dedicated to I.O.M. Teutanus and to all the gods and goddesses on 11th of June. The names of the emperors and consules were erased. The altar could have been erected in the time of Philippus or Gallienus.

The other group of the altar-stones was erected by soldiers to I.O.M. so they cannot be directly connected to the Teutanus problem.

Large, profiled bases usually belong to the altars of Teutanus. So during the secondarily usage of the altars the bases were also transported to Bölcske, which suggests that at the time of the conveyance the monuments could have stood at their original erection place. The altar-stone of T. Fl. Titianus, another altar of whom is known from the Gellérthegy, Rezeda Street, helped to clarify the original place of the altars. Its wording is similar to the one’s found in Bölcske. The inscription from the Gellérthegy is unfortunately in fragmentary condition, the end of it is missing. T. Fl. Titianus and M. Aur(elius) erected the altar for the respect of I.O.M. T(eutanus), for the salvation of the emperor and for the prosperity of the civitas Eraviscorum. Titianus was an augur and on the basis of the analogy of Bölcske he could have been a duumvir in the colonia. According to Soproni, he was not an eraviscus augur, but in the first place the duumvir of the colonia who also held the office of the augur at the municipal gradation of ranks. Since the formulation of the stone from Bölcske is identical with the analogy from the Gellérthegy, the original erection-place of the altars must have been in the cult-centre of the eravisci. On the basis of the inscriptions, large, decorated altars with official character were erected by the office-holders of the municipium for the main god of the eravisci, Teutanus and for the salvation of the emperor and the civitas Eraviscorum in every year on 11th of June.

On the altar found in 1888 the elucidation of the god’s name cannot be read, so in the following period, many attempts exsisted for elucidation: Tavianus, Taraucus and Taranis. Then the altar found in the Szépvölgyi Street in 1953 clarified the elucidation as Teutanus. Afterwards, connecting Teutanus with the Gallic Toutates was obvious. The literary occurrence of the name can be read in Lucanus’s (Pharsalia I 444-446) and Lactantius’s (Div. Instit. I. 21,3) works. Apart from the similarity of the names, there isn’t any proof for the consonance of the two gods.

The word Teutanus originates from the Indo-European or Protoindo-European "teut"-root with a Latin derivative. The question is whether this word is the proper noun of the eraviscus god or it is an attribute of Iupiter formed by the Romans. It has to be clarified whether the similarity of the names Teutanus-Toutates refers only to etymological connection or it means relationship of the cults, because the stem of both Toutates and Teutanus is the Indo-European "teut"-root. From this root originates the "tout" at the western Celtic population, the "tuat" at the Celtic population of the island where the original diphtong –eu- didn’t remain. These variants correspond to the froms Toutates, Totates. Contrary to this, in the Central-Danube region and in Illyrian language area, the original Indo-European "teut"-root survived. This diphtong can be seen in the cases of Pannonian proper names as well: Breucus, Creusa, Deuco, Deuso, Reuso, Seuso. Is the survival of the "eu"-root in the Central-Danube region a relic of an Illyrian substratum from before the Celtic settling down? An argument in favour of it would be the name of the Illyrian queen, Teuta and the place-name of Teutoburgium in Syrmia. Anyway, the "teut"-root survived both as a proper- and a place-name in the Central-Danube region. In connection with the etymology of the name Toutates the research represents two viewponts:

It’s interesting that while the Gallic Toutates is represented as Mercurius and Mars in relation to the Roman interpretation, Teutanus appears like Iupiter. In Noricum, Toutatis appears next to Mars Latobicus. Thus, identifying Teutanus with the Gallic Toutates seems to be a misconclusion.

It’s also questionable whether the usage of the word Teutanus refers to a Celtic god and cult that lived on in the Roman period. The Pannonian Teutanus word cannot be originated from the combination of Teuto-tati, because the stem is completed with the Latin "–anus" derivative. Teutanus is firstly mentioned 130 years later after the Roman conquest on the Gellérthegy. Geographical names, cognomen and nomen gentile with Latin derivative and ancestral stem appear in similar ways from the province. So the word Teutanus is an attribute formed by the Romans, namely a cognomen of Iupiter, and it means: Iupiter from the Teutanus. The earliest altar can be dated back to 182 AD., although the beginning of the erections is not known, it could hardly have started before the foundation of the municipium of Aquincum. One group of the Pannonian place-names was created with the "-ianus" derivative from an ancestral stem (Bassiana, Tricciana, Caesariana). In the case of these namings, not only a settlement but a mountain sanctuary was mentioned as well, so the mountain was the subject of the naming and a proper noun was created with an attribute from it.

If we accept this supposition, this kind of practice of naming fits in with the naming of I.O.M. K(arnuntinus) in Pfaffenberg. According to it, Karnuntinus preserved the geographical name of the mountain when the sanctuary-area was founded. The adjective Teutanus on the altars suggests that it was a proper noun in the time of the Roman conquest and the Romans took it over from the language of the eravisci.

How did the adjective Teutanus of Iupiter come into being? Endre Tóth thinks that Aquincum was the original name of the Celtic oppidum on the Gellérthegy. After the occupation of the province, the population was removed and a legio camp was built there which needed a name so taking over the name of the native settlement seemed to be obvious. It is proved by the fact that Aquincum isn’t a word of Latin origin, it means "place with wells". On the northeastern and southeatern part of the Gellérthegy, numerous hot water sources can be found indeed. Taking over the name meant that the Gellérthegy remained without a name, because it wasn’t connected to the settlement. Thus, a new name was found from the natives’ language: Mons Teutanus = hill of the natives. Later the hill became a place of religious traditions and altars were dedicated with specific regularity by office-holders from Aquincum to I.O.M. Teutanus, so the name of the Mons Teutanus became a distinctive attribute of Iupiter. The Romans used to respect gods with different adjectives at different places (e.g. Iupiter Tavianus, Arubianus, Heliopolitanus, Dolichenus). The god of the Mons Teutanus became a distinguising attibute of Iupiter in the Empire.

The function and the topographical placing of Pfaffenberg are similar to the ones of the Gellérthegy. Both places were a governor’s seats and legio camp, the municipium rank was given by Hadrian to them at the same time, then the colonia rank by Septimius Severus.

However, there are differences between the altars erected on the two find places: the sanctuary of the Gellérthegy lied in a civil, administrative area, but Pfaffenberg lied in a military territory. On the Gellérthegy, the office-holders of the town erected the altars, but on Pfaffenberg, the altars can be connected only to the cives Romani consistenses Carnunti. In Aquincum, the altars were dedicated to the respect of I.O.M. Teutanus, to the salvation of the emperor and to the survival of the community of Aquincum, but similar to the latter doesn’t occur on Pfaffenberg.

The date of the dedication is 11th of June both in Aquincum and in Carnuntum. On the basis of the Roman calendar, it is the feast of Matralia, but our inscriptions and the inscriptions from the other parts of the Empire have nothing to do with it. There are more possibilities to explain the date of the dedication.

According to the first one, the reason for the same date of the dedication can be the same historical past of the two cities and it could be in connection with Pannonia. According to Géza Alföldy, the date could have been the foundation of Pannonia, while according to I. Piso, the date is thought to be the foundation of the first temple of the Capitolian Triad. Conforming to Sándor Soproni, the reason for it could be division of the province into two parts on 11th of June or some kind of a survived Celtic feast. According to K. Póczy and M. Pető, the date could have been the foundation date of both cities and E. Tóth thinks that this is the commemoration feast of the foundation of the sanctuaries which was a generally accepted custom in the Roman religion. June 11, as the date of the foundation of the municipium is questioned by the fact that the altars in Carnuntum weren’t erected by the quattuorviri.

According to an earlier assumption, the date, 11th of June (CIL III 3347), written on the inscriptions of Carnuntum and Székesfehérvár, could be connected to the"rain-wonder" of the military expedition led by Marcus Aurelius in 172 AD. But further research has disproved it. The new dating of the stone of Székesfehérvár is 11th of June in 178 AD instead of 172 AD. In this case, altars must have been erected in Aquincum and in Carnuntum on the day of the "rain-wonder", but this is unlikely.

The stone of Székesfehérvár was dedicated not only to the emperors but to the ordo of Aquincum. It could refer to the fact then that 11th of June could have been the feast-day of the foundation of Aquincum and perhaps of Carnuntum municipium as well.

So the most problematic question is the explanation of the date, 11th of June. The question cannot be clearly answered on the basis of our actual knowledge. But the time of the sanctuaries’building is also problematic, it is not known if both sanctuaries were built at the same time or the sanctuary of Carnuntum is earlier than the one of Aquincum and had served as a model for the latter. The usage of Pfaffenberg as a cult-centre began in the 2nd half of the 1st cent. AD., but the Iupiter-altars were erected later, like in Aquincum.

It seems that on Pfaffenberg and Gellérthegy, where

the presence of the natives is proved, the cults appearing in the 2nd

cent. AD. cannot be necessarily regarded as a living on of the native cults.

Alföldy, G., ’Aquincum vallási életének története’ Budapest Régiségei 20(1963), 47-69.

Beszédes, J. - Mráv Zs. - Tóth E., ’Die Steindenkmaler von Bölcske-Inschriften und Skulpturen-Katalog’ In: Szabó, A. – Tóth, E., Bölcske, römische Inschriften und Funde. Budapest 2003, 103-218.

Bónis, É., Die spätkeltische Siedlung Gellérthegy-Tabán in Budapest. Budapest 1969.

Fitz, J. (ed.), Religious and cults in Pannonia. Székesfehérvár 1998.

Jobst, W., ’Carnuntum. Der Pfaffenberg als Sacer Mons Carnuntinus’ in: Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II/6, 701-720.

Jobst, W., Carnuntum Pfaffenberg 1985. Carnuntum Jahrbuch 1986, 65-127.

Mócsy, A. – Fitz, J. (ed.), Pannonia régészeti kézikönyve. Budapest 1990.

Mócsy, A., Pannonia a késői császárkorban. Budapest 1974.

Mócsy, A., Pannonia a korai császárság idején. Budapest 1974.

Nagy, T., ’Budapest története az őskortól a honfoglalásig’ In: Budapest története az őskortól az Árpád kor végéig. Budapest 1973, 120.

Nováki, Gy. – Pető, M., ’Neuere Forschungen in spätkeltischen oppidum auf dem Gellértberg in Budapest’ Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 40(1988) ,83-99.

Pető, M, ’A gellérthegyi kőbánya’ Budapest Régiségei 32(1998) 123-133.

Petres, É.F. ’On celtic animal and human sacrificies’ Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 24(1972) ,365-383.

Póczy, K., ’A Gellérthegy-tabáni telep topográfiájához’ Archaeologiai Értesítő 72(1959) 63-69.

Soproni, S., ’Előzetes jelentés a bölcskei késő római ellenerőd kutatásáról’ Communicationes Archaeologicae Hungariae 1990, 130-141.

Szőke, M., ’Building Inscription of a Silvanus Sanctuary from Cirpi (Dunabodány)’ Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 23(1971), 221-224.

Tóth, E., ’Die Iupiter Teutanus Ältare’ In: Szabó, A.-Tóth, E., Bölcske, römische Inschriften und Funde. Budapest 2003, 385-438

Tóth, E., ’Silvanus Viator’ Alba Regia 18(1980) 91-101.

Visy, Zs. (ed.), Magyar régészet az ezredfordulón. Budapest 2003.