Newcomers

In

the last half-century BC, new population groups arrived in the southern

Netherlands, and mixed with the local population. Around the beginning

of the first century AD there were at any rate two such new population

groups in the southern Netherlands whose name we know for certain: the

Batavians in the river area, and the Cananefates along the coast of

Zuid-Holland province. It is however difficult to pinpoint exactly

which group lived where. For more information, see ‘The province’s

indigenous population’.

In

the last half-century BC, new population groups arrived in the southern

Netherlands, and mixed with the local population. Around the beginning

of the first century AD there were at any rate two such new population

groups in the southern Netherlands whose name we know for certain: the

Batavians in the river area, and the Cananefates along the coast of

Zuid-Holland province. It is however difficult to pinpoint exactly

which group lived where. For more information, see ‘The province’s

indigenous population’.

Landscape

Archaeological

remains repeatedly highlight the differences (and similarities) between

regions in the Netherlands. These regions correlate well with the

different types of landscape, as the natural environment had a strong

bearing on whether an area was suitable for occupation. In the Roman

period large parts of our country were wet and barely accessible.

However, this did not mean that they were deserted; they were simply

occupied differently to drier areas. The Netherlands can in fact be

divided into a high, dry Pleistocene part in the south and east of the

country (the yellow and orange areas on the map) and a wet Holocene

part in the north and west (shown in blue).

Archaeological

remains repeatedly highlight the differences (and similarities) between

regions in the Netherlands. These regions correlate well with the

different types of landscape, as the natural environment had a strong

bearing on whether an area was suitable for occupation. In the Roman

period large parts of our country were wet and barely accessible.

However, this did not mean that they were deserted; they were simply

occupied differently to drier areas. The Netherlands can in fact be

divided into a high, dry Pleistocene part in the south and east of the

country (the yellow and orange areas on the map) and a wet Holocene

part in the north and west (shown in blue).

The land in the Pleistocene area formed during the last ice age, and

consists mainly of sandy soils. During the ice age, glaciers pushed up

large quantities of earth, forming ice-pushed ridges which give the

land some relief. Only the very south of Limburg province, with its

loamy loess deposits (orange areas on the map) is really hilly. People

have always been attracted to loess, as it produces such fertile soil.

The Holocene part was formed after the last ice age ended, some 10,000

years ago, in the delta of several rivers, and by the sea. The rivers

meandered through the low-lying landscape on their way to the sea. This

part of the country consists largely of clay and peat. Small rivers

with higher banks wound their way through the peatlands. However, most

of the land was wet and virtually inaccessible.

Farmers on wet and dry soils

It is interesting to note that virtually all pre-Roman settlements are similar in size and in the archaeological finds they yield. The fact that there were few, if any, central places in the Netherlands was probably due among other things to the traditions and way of life of the indigenous population. The wet areas and the sandy soils of Brabant and the east were populated mainly by stockbreeders who reared cattle and horses. Arable farming probably produced too small a yield in these areas. Only in the very south of the country, on the loamy loess soils of southern Limburg, was arable farming the mainstay of the population.

Cattle farmers

Indigenous stockbreeders kept cattle in their farmhouses, which included both living quarters and animal stalls under one roof. Grazing cattle required a lot of land, so settlements lay far apart, and it would be impossible for a stockbreeder to live in a town or larger settlement. Indeed, there were probably no such settlements at that time. The region around Kessel and Lith nevertheless seems to have played a central role in the river area, though it should be noted that the eastern river area is one of the most intensively investigated parts of the country. Kessel and Lith are located at the spot where two major rivers – the Waal and the Maas – meet. This was an important location. An important shrine here attracted people from far and wide even before the arrival of the Romans. Similar shrines were also built in Elst and in the village of Empel in Brabant. However, there was probably no such thing as a capital at that time.

Unique Batavians

We know from

historical sources that the Batavians had a special status in the Early

Roman period.

They had probably befriended and concluded agreements with the Romans

before

they moved to the Dutch river area. This friendship continued after the

Batavians moved. The agreements, under which the Batavians were not

required to

pay taxes in the form of money or goods, remained in force. They were

however

obliged to provide soldiers, and Batavian warriors were highly prized.

Large

numbers of young men left their families and joined the Batavian units

in the

Romany army. The other population groups in the Netherlands, including

the

Cananefates and probably also the Sturii and Marsaci, also provided

troops for

the Romans. All soldiers came into contact with Roman culture during

their

military service. They were obliged to adopt a Roman soldier’s way of

life, and

many of them therefore learnt to read and write.

Many of the settlements that have been excavated date from around the beginning of the present era. However, some of them appear to have been occupied as long ago as the mid-first century BC, remaining in use into the Roman period.

Shifting farmsteads

In the Iron Age, land division took the form of ‘shifting farmsteads’. Iron Age farmhouses, which combined animal and human accommodation under one roof, were in the middle of the fields. Small barns for storing the harvest stood beside the main house. The farmstead was regularly moved, so that other fields could be brought under cultivation, while the farmer remained close to his land.

A permanent pitch

From the Late Iron Age onwards, people began to settle at fixed spots in the landscape. When a house needed replacing, it would be rebuilt on more or less the same site. A shallow ditch (probably with a hedge or fence) would be dug around the farmhouse and outbuildings. This clearly divided the farmstead from its surroundings, and prevented animals – wild or domesticated – from entering or leaving the farm. The ditch also seems to have served to distinguish each farmstead from the rest, as people apparently became more conscious of their possessions. Some larger settlements were in fact entirely fenced in.

Changes

The Iron Age

occupation differed in a number of respects from the occupation in the

Roman

period. The changes to houses and settlements at the end of the Iron

Age, in

the last fifty or hundred years BC, are striking. Because people were

living

for longer on the same spot, their houses became more robust. The

roof-bearing

central pillars became thicker, and stood in deeper pits. The

orientation of

the houses also seems to have changed. For the first time, larger

settlements

comprising more than a few farms began to emerge, as people developed a

tendency to live in greater proximity to each other as they became more

settled.

The

majority of settlements consisted of no more than three or four

contemporaneous farms with outbuildings and wells. The people still

lived in farmhouses combining human and animal living quarters. If we

map the occurrence of certain house types and different types of

handmade pottery, we find that certain customs dominated in certain

regions. The boundaries between the different regions appear to

coincide with the boundaries between different landscapes and soil

types. The regions are also reasonably consistent with the territories

of certain population groups as described in Roman texts, although such

apparent links should be viewed with caution. In this way, three

regions can be distinguished in what was later to be the Roman part of

the Netherlands: the southeastern Netherlands (now the provinces of

Noord-Brabant and Limburg), the coastal area (Zuid-Holland and Zeeland)

and the river area (part of the present-day provinces of Gelderland and

Utrecht). Though slight differences can be discerned within this rough

division, there seems to have been little difference between regions in

terms of the size and layout of settlements.

The

majority of settlements consisted of no more than three or four

contemporaneous farms with outbuildings and wells. The people still

lived in farmhouses combining human and animal living quarters. If we

map the occurrence of certain house types and different types of

handmade pottery, we find that certain customs dominated in certain

regions. The boundaries between the different regions appear to

coincide with the boundaries between different landscapes and soil

types. The regions are also reasonably consistent with the territories

of certain population groups as described in Roman texts, although such

apparent links should be viewed with caution. In this way, three

regions can be distinguished in what was later to be the Roman part of

the Netherlands: the southeastern Netherlands (now the provinces of

Noord-Brabant and Limburg), the coastal area (Zuid-Holland and Zeeland)

and the river area (part of the present-day provinces of Gelderland and

Utrecht). Though slight differences can be discerned within this rough

division, there seems to have been little difference between regions in

terms of the size and layout of settlements.

The southeastern Netherlands: arable farmers and stockbreeders

We

know that

the Texuandri and the Cugerni lived in the southeastern Netherlands

around the

beginning of the present era. The region divides into two main areas:

the

fertile loess soils in the hills of southern Limburg, and the poorer

sandy

soils of Brabant and northern Limburg. A continuous development in

house

building can be seen in this region. The farmhouses were two-aisled, a

row of

roof-bearing pillars in the middle of the house dividing it in two. The

pottery

also shows continuous development from the Iron Age into the Roman

period.

Smaller houses are also found sporadically in this region, mainly in

the loess

area. They were probably separate houses or animal stalls, instead of

the

combined farmhouses found elsewhere.

We

know that

the Texuandri and the Cugerni lived in the southeastern Netherlands

around the

beginning of the present era. The region divides into two main areas:

the

fertile loess soils in the hills of southern Limburg, and the poorer

sandy

soils of Brabant and northern Limburg. A continuous development in

house

building can be seen in this region. The farmhouses were two-aisled, a

row of

roof-bearing pillars in the middle of the house dividing it in two. The

pottery

also shows continuous development from the Iron Age into the Roman

period.

Smaller houses are also found sporadically in this region, mainly in

the loess

area. They were probably separate houses or animal stalls, instead of

the

combined farmhouses found elsewhere.

Along the coast: living with water

The

coastal

region was mainly characterised by wet peaty areas and higher coastal

barriers.

The latter would have been the only parts of this landscape that really

leant

themselves to occupation. Prior to the Roman period, large tracts of

land

behind the dunes were inundated and in some areas the soil was for a

long time

too wet to live on. This can often be clearly seen in excavations

around the

Maas estuary. A layer of clay deposited during flooding is often found

between

Iron Age and Roman features. In the peaty area of Midden-Delfland (just

north

of the Maas estuary), however, signs of continuous occupation have been

found.

Remarkably, settlements on the peat appear to have been continuously

occupied,

while those on clay were not.

The

coastal

region was mainly characterised by wet peaty areas and higher coastal

barriers.

The latter would have been the only parts of this landscape that really

leant

themselves to occupation. Prior to the Roman period, large tracts of

land

behind the dunes were inundated and in some areas the soil was for a

long time

too wet to live on. This can often be clearly seen in excavations

around the

Maas estuary. A layer of clay deposited during flooding is often found

between

Iron Age and Roman features. In the peaty area of Midden-Delfland (just

north

of the Maas estuary), however, signs of continuous occupation have been

found.

Remarkably, settlements on the peat appear to have been continuously

occupied,

while those on clay were not.

We know from historical sources that the Cananefates lived in the coastal area between the Maas and the Rhine at the beginning of the Roman period. The Marsaci, Sturii and Frisiavones lived to the south of the Maas estuary, in present-day Zeeland and the west of Brabant province.

The pottery

and houses of all coastal inhabitants, including those north of the

Rhine, are very similar. The differences

between the housing and pottery of the Frisians to the north of the

Rhine (who were never really part of the Roman empire) and those of the

inhabitants of the

coastal zone to the south became more marked during the Roman period.

However,

around the beginning of the present era, the houses in both regions

were

largely two- or three-aisled, although single-aisled houses have also

been

found in several places south of the Rhine. The three-aisled houses to

the south

of the Rhine had an extra feature: the outside posts stood diagonally,

forming

a kind of ‘A’ shape. Furthermore, in Midden-Delfland (an area that lies

between

Rotterdam, Delft, The Hague and the coast), ‘wall-ditch houses’ from

the first

half of the first century AD have been found. Traces of such houses are

found

in the soil in the form of a ditch surrounding a turf embankment. This

type of

house had already been found in Assendelft in Noord-Holland province,

well north

of the Rhine.

However,

around the beginning of the present era, the houses in both regions

were

largely two- or three-aisled, although single-aisled houses have also

been

found in several places south of the Rhine. The three-aisled houses to

the south

of the Rhine had an extra feature: the outside posts stood diagonally,

forming

a kind of ‘A’ shape. Furthermore, in Midden-Delfland (an area that lies

between

Rotterdam, Delft, The Hague and the coast), ‘wall-ditch houses’ from

the first

half of the first century AD have been found. Traces of such houses are

found

in the soil in the form of a ditch surrounding a turf embankment. This

type of

house had already been found in Assendelft in Noord-Holland province,

well north

of the Rhine.

The river area: between north and south

The river area

was home to the Batavians in the last half-century BC. Their houses

clearly

reflect the area’s position between the north and the south. Some are

two-aisled, resembling those in the southern sandy areas. Other houses

are

three-aisled, as commonly found to the north of the Rhine. Many houses

were in

fact a combination of two traditions, with a three-aisled and a

two-aisled

part. The former probably housed the animals. Smaller houses with no

animal

stalls also occurred in the region in the Early Roman period. The

settlements

were sometimes separated from the outside world by ditches. These

ditches also

provided essential drainage, of course. In terms of finds, too, the

Batavians

differ from the other population groups, for example in terms of coins

that are

found only in their territory.

|

|

Dating problems

Indigenous

settlements continued to exist throughout the entire Roman period. Some

of them

were continuations of Iron Age settlements. It is however difficult to

establish when the first people came to live in a settlement, as most

of the

pottery found there tends to be handmade. This kind of pottery is

difficult to

date accurately, so such settlements are generally held to have been

established some time between 50 BC and AD 50. Only when a settlement

is

comprehensively excavated does it become easier to determine an

accurate start

date, on the basis of the buildings found, among other things.

Indigenous

settlements continued to exist throughout the entire Roman period. Some

of them

were continuations of Iron Age settlements. It is however difficult to

establish when the first people came to live in a settlement, as most

of the

pottery found there tends to be handmade. This kind of pottery is

difficult to

date accurately, so such settlements are generally held to have been

established some time between 50 BC and AD 50. Only when a settlement

is

comprehensively excavated does it become easier to determine an

accurate start

date, on the basis of the buildings found, among other things.

Same people, new

settlement

It

is rarely possible to demonstrate continuous occupation from the Late

Iron Age into the Roman period. This does not however mean that the

people disappeared, or that the transition to the Roman period brought

new people to the settlement. It is quite possible that settlements

moved, so a settlement from the beginning of the Roman period that

looks new might in fact already have existed for some time.

It

is rarely possible to demonstrate continuous occupation from the Late

Iron Age into the Roman period. This does not however mean that the

people disappeared, or that the transition to the Roman period brought

new people to the settlement. It is quite possible that settlements

moved, so a settlement from the beginning of the Roman period that

looks new might in fact already have existed for some time.

Small settlements grow larger

Most small

settlements of no more than three or four contemporaneous farms

underwent few

changes. However, some grew in the first century into larger, sometimes

enclosed settlements. Examples of this include the settlements at Wijk

bij Duurstede-De Horden ,

Houten-Overdam, Oss-Westerveld, Hoogeloon and Voerendaal-Ten Hove.

|

New houses

New pots

The

Romanisation process can be seen in the finds made during excavations.

Despite

the presence of the Romans, in the first century AD the inhabitants of

the

entire southern Netherlands continued to use handmade pottery they

produced

themselves. Once the Romans had been in the Netherlands for a while,

however,

the indigenous inhabitants used more and more thrown pottery made on a

potter’s

wheel at a central workshop. This technique had been introduced by the

Romans.

The potters sold their wares in large parts of the province, and

handmade

pottery was used less and less. In the course of the second century

handmade

pottery in fact largely disappeared from most settlements. Only the

Cananefates

in the coastal area to the north of the Maas estuary stuck to the old

pottery

for longer. Even when thrown pottery was readily available, they still

preferred to use handmade pots.

The

Romanisation process can be seen in the finds made during excavations.

Despite

the presence of the Romans, in the first century AD the inhabitants of

the

entire southern Netherlands continued to use handmade pottery they

produced

themselves. Once the Romans had been in the Netherlands for a while,

however,

the indigenous inhabitants used more and more thrown pottery made on a

potter’s

wheel at a central workshop. This technique had been introduced by the

Romans.

The potters sold their wares in large parts of the province, and

handmade

pottery was used less and less. In the course of the second century

handmade

pottery in fact largely disappeared from most settlements. Only the

Cananefates

in the coastal area to the north of the Maas estuary stuck to the old

pottery

for longer. Even when thrown pottery was readily available, they still

preferred to use handmade pots.

Rust na de opstand

Tijdens de Romeinse tijd werden er veel nieuwe

inheemse

nederzettingen op het platteland gebouwd. Vooral nadat de Bataafse

opstand in

70 na Chr. was neergeslagen. Na deze opstand werd het rustig langs de

Rijn. De

handel kwam goed op gang en met de economie ging het steeds beter. De

invloed

van de Romeinse aanwezigheid op het platteland werd steeds zichtbaarder

bij het

verschijnen van enkele grote herenboerderijen in 'Romeinse' stijl (de

villae)

en kleine plattelandscentra. De bevolking groeide onder de gunstige

omstandigheden. Oude inheemse nederzettingen groeiden en er werden

nieuwe

nederzettingen gesticht.

Peace follows uprising

Many new indigenous settlements were built in rural areas during the Roman period, particularly after the Batavian revolt was suppressed in AD 70. After this revolt, the area along the Rhine enjoyed a long period of peace. Trade developed and the economy flourished. The impact of the Roman presence on the countryside became more and more visible, as several large ‘Roman-style’ homesteads (villae) and small rural centres appeared. The circumstances were conductive to population growth, and old indigenous settlements expanded at the same time as new settlements were being established.

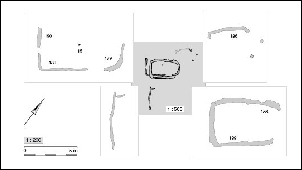

New settlements based on old traditions

These

new

settlements barely differed from the old ones, if at all, and old

traditions

were upheld. The presence of the Romans did not stop most indigenous

country

dwellers from building their houses according to their own traditions.

One

example of a new indigenous settlement has been found in Venray-de

Hulst. There

was already a settlement there in the Late Iron Age, but it was

abandoned by

the Early Roman period. In the second century, a new settlement was

established

a short distance away. This new settlement probably existed for 150

years. The

excavation plan shows many houses, though they would not all have

existed at

the same time. The settlement actually consisted of a few

contemporaneous farms

with outbuildings and wells.

These

new

settlements barely differed from the old ones, if at all, and old

traditions

were upheld. The presence of the Romans did not stop most indigenous

country

dwellers from building their houses according to their own traditions.

One

example of a new indigenous settlement has been found in Venray-de

Hulst. There

was already a settlement there in the Late Iron Age, but it was

abandoned by

the Early Roman period. In the second century, a new settlement was

established

a short distance away. This new settlement probably existed for 150

years. The

excavation plan shows many houses, though they would not all have

existed at

the same time. The settlement actually consisted of a few

contemporaneous farms

with outbuildings and wells.

Neighbours

Lieshout

has some good examples of the type of settlement found in the southern

Netherlands. Three settlements have been found here within a distance

of 400

metres. The largest was established around the beginning of the present

era,

and was abandoned sometime during the second half of the second

century. It

probably consisted of only two contemporaneous farms during the early

and final

phases. During its heyday, in the second half of the first century and

early

second century, however, there were probably four farms there.There

was at least one farm some 400 metres to the

west of the large settlement during the same period, around the end of

the

first century. Around AD 200, when the larger settlement had already

been

abandoned, two smaller settlements stood no more than 250 metres apart

there.

They probably did not last long, however, and had at any rate been

abandoned by

the middle of the third century. This is not unusual, in fact, as the

majority

of the indigenous-Roman occupation appeared to cease in the southern

Netherlands around AD 225.

Lieshout

has some good examples of the type of settlement found in the southern

Netherlands. Three settlements have been found here within a distance

of 400

metres. The largest was established around the beginning of the present

era,

and was abandoned sometime during the second half of the second

century. It

probably consisted of only two contemporaneous farms during the early

and final

phases. During its heyday, in the second half of the first century and

early

second century, however, there were probably four farms there.There

was at least one farm some 400 metres to the

west of the large settlement during the same period, around the end of

the

first century. Around AD 200, when the larger settlement had already

been

abandoned, two smaller settlements stood no more than 250 metres apart

there.

They probably did not last long, however, and had at any rate been

abandoned by

the middle of the third century. This is not unusual, in fact, as the

majority

of the indigenous-Roman occupation appeared to cease in the southern

Netherlands around AD 225.

Settlements in

the river area were similar to those in the southern Netherlands. Only

the

building methods differed. Farms also included small barns alongside

the

farmhouse. As in the southern Netherlands, wells provided fresh water

if there

was no surface water nearby.

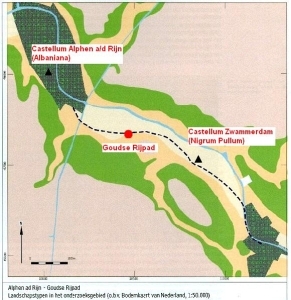

Notably,

there

were also indigenous settlements near to the Rhine, the border of the

Roman empire. Some archaeologists believe that

there was a military zone along both sides of the border which was

entirely

controlled by the army. If there was indeed such a zone in the

Netherlands,

this apparently did not mean that no indigenous people were allowed to

live

there. Several indigenous settlements have been excavated along the

Roman

border in the last few years, so the idea of a military zone along the

border

which was exclusively reserved for the military would not appear to

apply to

the Netherlands. Some of the settlements date to between AD 40/50 and

AD 200.

This means that they were built in the period when the border was

finalised,

and several new fortresses were built. The settlements ceased to exist

at more

or less the same time as a period of unrest along the border. The

settlements

near the border were small, like those in the rest of the country, with

no more

than three or four contemporaneous farms. The farms were exactly like

those in

other indigenous settlements. Farmers and their animals lived under one

roof,

in a farmhouse combining both human and animal quarters. They made most

of

their pots themselves, though later they made grateful use of the

attractive,

robust thrown pots that the Romans had imported. There were probably

therefore

no soldiers living in these settlements, as archaeologists have been

known to

conjecture, just ordinary indigenous farmers. The farmers in the border

area

could sell their surplus grain and cattle to the Roman military camps,

which

meant they would have encountered Roman goods and customs.

Notably,

there

were also indigenous settlements near to the Rhine, the border of the

Roman empire. Some archaeologists believe that

there was a military zone along both sides of the border which was

entirely

controlled by the army. If there was indeed such a zone in the

Netherlands,

this apparently did not mean that no indigenous people were allowed to

live

there. Several indigenous settlements have been excavated along the

Roman

border in the last few years, so the idea of a military zone along the

border

which was exclusively reserved for the military would not appear to

apply to

the Netherlands. Some of the settlements date to between AD 40/50 and

AD 200.

This means that they were built in the period when the border was

finalised,

and several new fortresses were built. The settlements ceased to exist

at more

or less the same time as a period of unrest along the border. The

settlements

near the border were small, like those in the rest of the country, with

no more

than three or four contemporaneous farms. The farms were exactly like

those in

other indigenous settlements. Farmers and their animals lived under one

roof,

in a farmhouse combining both human and animal quarters. They made most

of

their pots themselves, though later they made grateful use of the

attractive,

robust thrown pots that the Romans had imported. There were probably

therefore

no soldiers living in these settlements, as archaeologists have been

known to

conjecture, just ordinary indigenous farmers. The farmers in the border

area

could sell their surplus grain and cattle to the Roman military camps,

which

meant they would have encountered Roman goods and customs.

New land

Many new

settlements were built in the coastal area around the beginning of the

present

era, partly because more areas fell dry and became accessible for

occupation

and farming. The number of settlements rose sharply during the Roman

period.

Different building styles

The

predominant building style along the entire coast was the two- or

three-aisled

house. Single-aisled houses were also found to the south of the Rhine.

Despite

the major similarities within the coastal area to the south of the

Rhine,

the Maas estuary appears to marked a boundary.

The differences between the areas to the north and south of the estuary

became

more pronounced during the course of the Roman period. This can be seen

above

all in the pottery. Inhabitants of the area to the north of the estuary

continued to use their own indigenous pottery for a long time, even

when others

had already switched to using pottery introduced by the Romans.

The

predominant building style along the entire coast was the two- or

three-aisled

house. Single-aisled houses were also found to the south of the Rhine.

Despite

the major similarities within the coastal area to the south of the

Rhine,

the Maas estuary appears to marked a boundary.

The differences between the areas to the north and south of the estuary

became

more pronounced during the course of the Roman period. This can be seen

above

all in the pottery. Inhabitants of the area to the north of the estuary

continued to use their own indigenous pottery for a long time, even

when others

had already switched to using pottery introduced by the Romans.

Farmers on the peatlands

To

date, most

of the settlements found in Midden-Delfland, a large peaty area north

of the

Maas estuary, have been new. There is some evidence of a settlement on

the

peat, which was occupied from the Late Iron Age into the Roman period.

However,

most Late Iron Age farmers left their old home and moved their

settlements to sandy

creeks that had recently dried up and were higher and drier than the

surrounding wetlands. Occupation on peat causes the ground to slowly

sink under

the weight of the house and as a result of drainage through ditches. In

the

course of time, a dried-up sandy creek will therefore ‘rise’ above the

surrounding peatlands. Only small settlements have been excavated to

date,

usually consisting of only one house at a time. The settlement site

would be

defined by natural boundaries. In this way, a strip of settlements

formed along

the higher ridges in the landscape during the second century. People

often

built a small mound (terp) on which to build their house. The terps

consisted

mainly of turf and dung. The buildings in Midden-Delfland were often

built of

turf. Sometimes a house would be repeatedly rebuilt at the same spot by

each

successive generation, causing the site to be raised further and

further.

Hearths and ovens have been found both inside and outside the houses.

To

date, most

of the settlements found in Midden-Delfland, a large peaty area north

of the

Maas estuary, have been new. There is some evidence of a settlement on

the

peat, which was occupied from the Late Iron Age into the Roman period.

However,

most Late Iron Age farmers left their old home and moved their

settlements to sandy

creeks that had recently dried up and were higher and drier than the

surrounding wetlands. Occupation on peat causes the ground to slowly

sink under

the weight of the house and as a result of drainage through ditches. In

the

course of time, a dried-up sandy creek will therefore ‘rise’ above the

surrounding peatlands. Only small settlements have been excavated to

date,

usually consisting of only one house at a time. The settlement site

would be

defined by natural boundaries. In this way, a strip of settlements

formed along

the higher ridges in the landscape during the second century. People

often

built a small mound (terp) on which to build their house. The terps

consisted

mainly of turf and dung. The buildings in Midden-Delfland were often

built of

turf. Sometimes a house would be repeatedly rebuilt at the same spot by

each

successive generation, causing the site to be raised further and

further.

Hearths and ovens have been found both inside and outside the houses.

Everything in its place

Farmsteads

were laid out using a ditch system, which also provided drainage. The

ditches

created a number of blocks, each of which had its own function. The

house, the

vegetable garden, the outdoor animal shelters and the well were all

surrounded

by their own ditch. An example of this system can be seen at the Woudse

Polder

settlement.

Living on a terp

The

remains

found in the Dorppolder near Schipluiden were so well preserved that

many

details of the structure of the houses could be seen. The oldest house

dated

from the beginning of the first century AD. It stood on a small terp

made of

clay sods and dung. Each successive house was built on the remains of

the

previous one, and the most recent one dates from around AD 120. The

farmstead

was surrounded by a fence. The wet soil had also preserved remains of

the paths

leading to the house, which were made of branches. The floor of the

house

consisted of layers of dung and reeds. A path of reed or straw matting

had been

laid in the stalls, and the cattle stood between wattle partitions.

The

remains

found in the Dorppolder near Schipluiden were so well preserved that

many

details of the structure of the houses could be seen. The oldest house

dated

from the beginning of the first century AD. It stood on a small terp

made of

clay sods and dung. Each successive house was built on the remains of

the

previous one, and the most recent one dates from around AD 120. The

farmstead

was surrounded by a fence. The wet soil had also preserved remains of

the paths

leading to the house, which were made of branches. The floor of the

house

consisted of layers of dung and reeds. A path of reed or straw matting

had been

laid in the stalls, and the cattle stood between wattle partitions.

A large number

of drainage ditches were dug to keep the settlements in Midden-Delfland

dry.

They flowed into a main ditch that was well maintained and regularly

dredged.

This main ditch formed part of a much wider parcelling system

consisting of

ditches, which divided the land outside the settlement into blocks of

arable

land and pasture. The settlement was therefore situated within the

parcelling

system, whose ditches connected several settlements. The division of

land

became stricter during the Roman period, and it has been demonstrated

that

standard dimensions were used, indicating that land use was well

organised,

perhaps even by the Roman authorities.

What is a villa?

Many

new

settlements were founded during the Roman period. The most striking of

them

were the villae, which first appeared around the beginning of the

second

century. A Roman villa was a large homestead in the countryside. It

took the

form of a complex, with a main building and auxiliary buildings. One or

more of

the buildings would often feature architectural elements introduced by

the

Romans, such as stone walls, pillars and roof tiles. A villa produced a

surplus

of agricultural produce that could be sold in the towns or to the army.

Sometimes the owner would live at the villa, though some were also run

by a

bailiff or tenant. Villae were usually large farms, though some were

also

involved in non-agricultural activities.

Many

new

settlements were founded during the Roman period. The most striking of

them

were the villae, which first appeared around the beginning of the

second

century. A Roman villa was a large homestead in the countryside. It

took the

form of a complex, with a main building and auxiliary buildings. One or

more of

the buildings would often feature architectural elements introduced by

the

Romans, such as stone walls, pillars and roof tiles. A villa produced a

surplus

of agricultural produce that could be sold in the towns or to the army.

Sometimes the owner would live at the villa, though some were also run

by a

bailiff or tenant. Villae were usually large farms, though some were

also

involved in non-agricultural activities.

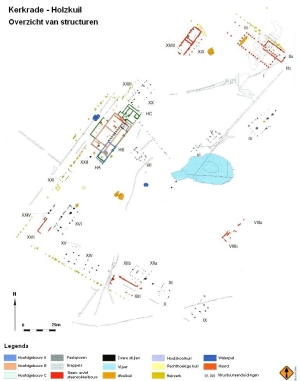

From wood to stone

The new villae

were sometimes built as simple wooden structures. Only later, in the

course of

the second century, were they rebuilt with stone foundations –

primarily the

main building, but also often some of the outbuildings. This

development can be

seen in the villa at Kerkrade-Holzkuil, in the fertile loess area of

southern

Limburg.

Settlements become villae

Besides the

new villae, a number of larger enclosed settlements were rebuilt in the

late

first and early second centuries. A large Roman-style main building

with

several auxiliary buildings would be built on the site of the old

farms. The

structure of the settlement was sometimes radically altered to create

an open

central courtyard, making it a true villa. Examples include the villae

at

Voerendaal-Ten Hove and Neerharen-Rekem (Belgium). Both are in the

fertile

loess area of the south.

|

|

|

Not quite a real villa

In other settlements, though an actual villa was not built, there was clearly some Romanisation of the buildings in the late first and early second centuries. One example is the enclosed settlement at Oss-Westerveld, where there was already a single homestead using specially imported Roman goods in the Early Roman period.

A

special house was built at this homestead at the end of the first

century. Though it was still a traditional two-aisled structure, it had

extra

posts around the edge, which have been interpreted as a colonnade

(porticus).

Such features were not found in indigenous building traditions; they

had been

adopted from Roman architecture. This special house was surrounded by

its own

ditch. Beyond this ditch the rest of the settlement comprised

traditional

farmhouses combining living quarters and animal stalls. Though the

entire

settlement is reminiscent of a Roman villa, the traditional buildings

and

layout are clearly not. Such settlements, similar to but not quite real

villae,

are known as proto-villae or villa-like settlements.

A

special house was built at this homestead at the end of the first

century. Though it was still a traditional two-aisled structure, it had

extra

posts around the edge, which have been interpreted as a colonnade

(porticus).

Such features were not found in indigenous building traditions; they

had been

adopted from Roman architecture. This special house was surrounded by

its own

ditch. Beyond this ditch the rest of the settlement comprised

traditional

farmhouses combining living quarters and animal stalls. Though the

entire

settlement is reminiscent of a Roman villa, the traditional buildings

and

layout are clearly not. Such settlements, similar to but not quite real

villae,

are known as proto-villae or villa-like settlements.

|

From settlement to villa: a big step

The biggest

difference between indigenous settlements and Roman villae lay in the

fact that

villae had to make a profit from the sale of their agricultural

produce. They

therefore no longer produced merely for their own consumption, but for

trading.

This was a new phenomenon in the Netherlands. The villa-like

settlements were

probably also commercial operations, but the inhabitants were less

concerned

with the appearance of the settlement. ‘Real’ villa buildings differed

considerably from traditional buildings in terms of their appearance,

as they

included Roman architectural features. Villa-like settlements or

proto-villae

did not therefore have the appearance of a ‘full-blown’ villa. It is

not

certain whether such a settlement would ever have been able to develop

into a

‘real’ villa. It took a lot of money to build a villa in the true Roman

style,

and most settlements would probably not be able to afford it. However,

they

might be able to pay for a colonnade around a traditional wooden house,

to give

it a more Roman appearance. Another possibility is that, though these

people

could afford to build a villa, they chose not to, as they had no desire

to

adopt Roman culture.

The indigenous wealthy

It would

appear that the indigenous people of the Netherlands themselves often

undertook the

construction of a villa, as suggested by the Late Iron Age or Early

Roman

period settlements found immediately beneath a number of villa.

Villa-like settlements

might also be interpreted as a sign that this occurred. But how did the

indigenous population know how to build a villa? They would probably

have

turned to the towns, where people from other parts of the Roman empire

lived, for help. The architecture of

the Romanised buildings was almost entirely unknown to the indigenous

population, though the idea of enclosing and structuring a settlement

was not.

The enclosed settlements from the Late Iron Age were also often

structured to

some extent around an open area.

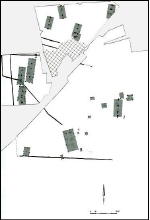

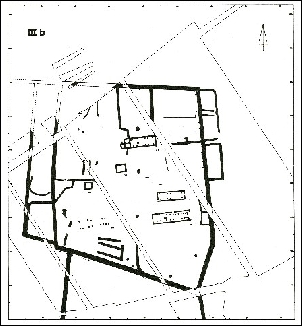

Hoogeloon: villa inside an indigenous settlement

The

settlement

at Hoogeloon represents an intermediate stage between a real villa and

a villa-like

settlement. The settlement was first established around the beginning

of the

present era, with four contemporaneous traditional farmhouses. At the

end of

the second century AD a villa building was erected in the settlement.

This

building was highly Romanised, and included a heated bathing facility,

a

porticus and its own palisade right from the outset. Recent research

has

revealed a number of new aspects that are not included in the plan

shown here.

A second courtyard containing only a well and a cattle pen was created

outside

the palisade around the main building. Outside this area there were

three

traditional farmhouses. The plan shows many more houses, though they

were

probably not contemporaneous. The villa building was abandoned in the

late

second century, having existed for no more than a hundred years. The

unique

thing about the settlement in Hoogeloon is the combination of a truly

Romanised

villa building and a completely traditional indigenous settlement. The

villa

building was clearly given its own special place in the settlement. It

was

built over part of the old settlement enclosure, allowing the

farmhouses in the

rest of the settlement to remain, and was also oriented in the same way

as the

existing buildings.

The

settlement

at Hoogeloon represents an intermediate stage between a real villa and

a villa-like

settlement. The settlement was first established around the beginning

of the

present era, with four contemporaneous traditional farmhouses. At the

end of

the second century AD a villa building was erected in the settlement.

This

building was highly Romanised, and included a heated bathing facility,

a

porticus and its own palisade right from the outset. Recent research

has

revealed a number of new aspects that are not included in the plan

shown here.

A second courtyard containing only a well and a cattle pen was created

outside

the palisade around the main building. Outside this area there were

three

traditional farmhouses. The plan shows many more houses, though they

were

probably not contemporaneous. The villa building was abandoned in the

late

second century, having existed for no more than a hundred years. The

unique

thing about the settlement in Hoogeloon is the combination of a truly

Romanised

villa building and a completely traditional indigenous settlement. The

villa

building was clearly given its own special place in the settlement. It

was

built over part of the old settlement enclosure, allowing the

farmhouses in the

rest of the settlement to remain, and was also oriented in the same way

as the

existing buildings.

Rijswijk: a villa in the coastal region

Another

example of this type of settlement can be found in Rijswijk in the

province of

Zuid-Holland. Here, the main building even had wall paintings and walls

built

partly of stone – highly recognisable Romanised features. The auxiliary

buildings were however built according to the old methods and the

settlement

has the appearance of a not entirely Romanised villa. The ground plan

of the

Rijswijk villa (on Tubasingel) has been reconstructed in a local park,

allowing

visitors to trace its position and layout.

Another

example of this type of settlement can be found in Rijswijk in the

province of

Zuid-Holland. Here, the main building even had wall paintings and walls

built

partly of stone – highly recognisable Romanised features. The auxiliary

buildings were however built according to the old methods and the

settlement

has the appearance of a not entirely Romanised villa. The ground plan

of the

Rijswijk villa (on Tubasingel) has been reconstructed in a local park,

allowing

visitors to trace its position and layout.

Houten: villae in the river area

Villae or villa-like

buildings also existed in the river area. Small sections of a number of

villae

have been identified. One example is the villa in Houten-Molenzoom.

Here, two

rows of foundation pits – pits filled with rubble that provided

foundations for

wooden posts – have been found, suggesting that a building with a

colonnade

once stood here. Remains of two Late Iron Age buildings have also been

found in

the immediate vicinity, so the spot had been inhabited for a long time.

Even

before the building with the colonnade was erected, another building

nearby was

decorated with wall paintings, remains of which have been found among

the

rubble in the pits. We do not however know what this earlier building

would

have looked like.

The

ground

plan of another villa in Houten can be seen in the paving on

Burgemeester

Wallerweg in the town centre. Several Late Iron Age or Early Roman

period

features have been found here, but the most interesting are the remains

of a

Roman villa building. Three successive buildings stood on this site in

the

Roman period. The first farm was built somewhere between AD 50 and 75.

It was a

wooden building, only the northern half of which has been excavated.

Between

approximately AD 110 and 120 a second farm was built, again from wood.

In this

case, too, only a small part of the farm has been excavated. The third

building

was built somewhere between AD 150 and 175. It had stone foundations

and a

porticus (colonnade) on the north side. Glazed windows, wall paintings

and

hypocaust heating tell us that this was a luxurious home.

Unfortunately, the

rest of the villa complex has not been excavated, so we do not know

whether

this was a ‘real’ villa or a villa-like settlement, similar to that

found in

Hoogeloon, for example.

The

ground

plan of another villa in Houten can be seen in the paving on

Burgemeester

Wallerweg in the town centre. Several Late Iron Age or Early Roman

period

features have been found here, but the most interesting are the remains

of a

Roman villa building. Three successive buildings stood on this site in

the

Roman period. The first farm was built somewhere between AD 50 and 75.

It was a

wooden building, only the northern half of which has been excavated.

Between

approximately AD 110 and 120 a second farm was built, again from wood.

In this

case, too, only a small part of the farm has been excavated. The third

building

was built somewhere between AD 150 and 175. It had stone foundations

and a

porticus (colonnade) on the north side. Glazed windows, wall paintings

and

hypocaust heating tell us that this was a luxurious home.

Unfortunately, the

rest of the villa complex has not been excavated, so we do not know

whether

this was a ‘real’ villa or a villa-like settlement, similar to that

found in

Hoogeloon, for example.

Country estate or farm?

There were in

fact two types of villa in Italy and the old provinces of the Roman

empire: the villa urbana and the villa rustica. A villa urbana was

inhabited by the owner himself,

though perhaps not always continuously, as he would also have a house

in town.

Although a villa urbana was a farm, it functioned mainly as a

peaceful retreat in the countryside. At a villa rustica, by contrast,

the

emphasis was on farming. It was often inhabited and run by a bailiff or

tenant,

and the owner would have visited only on rare occasions. Excavation

results in

the Netherlands do not allow us to identify the

difference between a villa urbana and a villa rustica. It is therefore

assumed that a villa urbana, where a wealthy owner would spend a

lot of his time, would be more luxurious, while a villa rustica would

have been

more practical. The term villa rustica is therefore use for villae that

were

clearly largely oriented towards farming. Villa urbana is reserved for

very large, luxurious

villae.

A villa as a business

Most of the

villae in the Netherlands were probably villae rusticae. They are

unlikely to

have been very spacious and luxurious, and the entire homestead would

have been

designed with practicality and production in mind. However, it is

assumed that

the owner would have lived there himself, unlike at the original villae

rusticae.

Luxury villa with fine views

Only

one villa

in the Netherlands is regarded as a villa urbana. It is the ‘Plasmolen’

villa on St.

Jansberg near Mook, to the south of Nijmegen. This large villa, built

around

the beginning of the second century, stood on a specially created

terrace on a

hillside. From its high vantage point,

the villa commanded a magnificent view over the Maas valley and the

surrounding

area. Inside it was decorated with wall paintings. A special heating

system

that had been installed in some rooms supplied heat under the floor and

through

pipes behind the walls. There were also heated baths in the house

itself.

Because the building stood on a hillside there was no room for any

outbuildings. They may well have been at the bottom of the hill, though

none

have been found to date. Plasmolen is regarded as a villa urbana

because of its size and location,

which is still a noticeable feature in the landscape. The villa has

been

partially reconstructed on its original site, on the flat terrace

halfway up

the side of St. Jansberg hill, which is covered in trees nowadays.

Only

one villa

in the Netherlands is regarded as a villa urbana. It is the ‘Plasmolen’

villa on St.

Jansberg near Mook, to the south of Nijmegen. This large villa, built

around

the beginning of the second century, stood on a specially created

terrace on a

hillside. From its high vantage point,

the villa commanded a magnificent view over the Maas valley and the

surrounding

area. Inside it was decorated with wall paintings. A special heating

system

that had been installed in some rooms supplied heat under the floor and

through

pipes behind the walls. There were also heated baths in the house

itself.

Because the building stood on a hillside there was no room for any

outbuildings. They may well have been at the bottom of the hill, though

none

have been found to date. Plasmolen is regarded as a villa urbana

because of its size and location,

which is still a noticeable feature in the landscape. The villa has

been

partially reconstructed on its original site, on the flat terrace

halfway up

the side of St. Jansberg hill, which is covered in trees nowadays.

Villae in

the Netherlands

Early investigations

Most

of our

information about Roman villae in the Netherlands comes from the south

of

Limburg. Many Roman villae have been excavated there, largely in the

19th and

early 20th centuries. Since archaeology was not practised according to

the same

standards then as it is today, our knowledge of these villae is

limited,

however. During excavations, the focus was largely on the architectural

and art

historical aspects of the buildings. Often, only one building would be

excavated, whereas villae consisted of several buildings. One exception

was the

villa at Bocholtz (also known as Vlengendaal), which was excavated

around 1912.

There, two outbuildings were also excavated.

Most

of our

information about Roman villae in the Netherlands comes from the south

of

Limburg. Many Roman villae have been excavated there, largely in the

19th and

early 20th centuries. Since archaeology was not practised according to

the same

standards then as it is today, our knowledge of these villae is

limited,

however. During excavations, the focus was largely on the architectural

and art

historical aspects of the buildings. Often, only one building would be

excavated, whereas villae consisted of several buildings. One exception

was the

villa at Bocholtz (also known as Vlengendaal), which was excavated

around 1912.

There, two outbuildings were also excavated.

Southern Netherlands

It

was not

until relatively recently that two villae were virtually completely

excavated:

Voerendaal-Ten Hove and Kerkrade-Holzkuil in the southern Limburg loess

area.

An almost complete excavation of the villa in Neerharen-Rekem, just

over the

Belgian border, has taught us more about the homestead itself and the

auxiliary

buildings. Analysis of seeds and pollen has added to our knowledge of

the

agricultural villa economy. Unfortunately, we know little about the

Dutch

villae further to the north. At Maasbracht, in the Maas valley,

however, the

main building of a villa has been excavated, giving us more information

about

villae in this area. The Maas valley was probably full of villae, but

very few

have been excavated.

It

was not

until relatively recently that two villae were virtually completely

excavated:

Voerendaal-Ten Hove and Kerkrade-Holzkuil in the southern Limburg loess

area.

An almost complete excavation of the villa in Neerharen-Rekem, just

over the

Belgian border, has taught us more about the homestead itself and the

auxiliary

buildings. Analysis of seeds and pollen has added to our knowledge of

the

agricultural villa economy. Unfortunately, we know little about the

Dutch

villae further to the north. At Maasbracht, in the Maas valley,

however, the

main building of a villa has been excavated, giving us more information

about

villae in this area. The Maas valley was probably full of villae, but

very few

have been excavated.

|

|

The river area

Things are

much the same in the river area. Surface finds suggest that there were

a

considerable number of villae there. However, only a few have been

extensively

excavated: of the 24 (probable) villae in the area, only nine have been

partially excavated. The single almost completely excavated villa or

villa-like

settlement in the river area is Druten-Klepperhei, where a number of

wooden

buildings and buildings with stone foundations have been found. A

wooden house

surrounded by a wooden porticus stood at the site of what is suspected

to have

been the main building. A stone cellar and bath house were also found

there,

along with many fragments of wall paintings. The main building was

probably

erected in the late first century, and abandoned in the second century,

having

existed for barely a hundred years. The rest of the settlement remained

for

longer, however. The excavation data from the villa at

Druten-Klepperhei are

being re-examined. It has been found that our old image and the ground

plan of

this villa probably require some adjustment, though exactly what kind

of

adjustment is not yet clear.

What did a villa look like?

Studies – both old and new – of villae in the Netherlands and just over the border have revealed a number of general features that are common to Dutch villae. A villa was an enclosed homestead, which included a main building with auxiliary buildings, a well or water storage facility and perhaps a pond. The site was enclosed by a ditch, hedge, fence, palisade or walls. In some cases, a shrine has been found at or near the homestead. The main building and several auxiliary buildings would usually have had stone foundations. They stood in a fairly ordered pattern around an open area in the centre of the homestead. Villae where the buildings were dispersed over the site are referred to by the German name ‘Streuhof’. On an ‘Axialhof’ the buildings were much more neatly arranged, with the main building on the main axis, and the majority of the auxiliary buildings on the two perpendicular axes, creating a central courtyard. Most of the villae excavated so far in the Netherlands have been of the ‘Axialhof’ type.

Auxiliary buildings

Little is

generally known about the function of the auxiliary buildings. They are

likely

to have been used for storage, housing animals, workshops and possibly

staff

accommodation. Sometimes a separate bath house was built, though

bathrooms were

often simply added to the main buildings. It was not uncommon for

several of

the outbuildings to be built partially of stone.

The main building

The

main

building or house generally consisted of a rectangular core, to which a

porticus (colonnade) and corner pavilions were often added. The house

would be

fairly symmetrical. Inside, some walls would be decorated with wall

paintings.

A number of rooms would be heated by means of hot air flowing under the

floor

and through the wall cavity (hypocaust heating). Many villae lost their

original symmetrical form as they were repeatedly expanded.

The

main

building or house generally consisted of a rectangular core, to which a

porticus (colonnade) and corner pavilions were often added. The house

would be

fairly symmetrical. Inside, some walls would be decorated with wall

paintings.

A number of rooms would be heated by means of hot air flowing under the

floor

and through the wall cavity (hypocaust heating). Many villae lost their

original symmetrical form as they were repeatedly expanded.

Visiting a Roman villa?

A

reconstruction of a Dutch villa in the municipality of Kerkrade is open

to

visitors. At Kaalheide, on the Krichelberg plateau (currently on the

edge of a

residential area), the foundations of the main building of a villa have

been

recreated in a local park, clearly revealing the ground plan of the

building.

The walls had stone foundations that protruded above the ground,

probably

supporting wattle and daub walls.

A

reconstruction of a Dutch villa in the municipality of Kerkrade is open

to

visitors. At Kaalheide, on the Krichelberg plateau (currently on the

edge of a

residential area), the foundations of the main building of a villa have

been

recreated in a local park, clearly revealing the ground plan of the

building.

The walls had stone foundations that protruded above the ground,

probably

supporting wattle and daub walls.

Work and private life

A villa

traditionally consisted of two parts: the pars urbana (also known as

the pars domestica) and

the pars rustica. The pars urbana was the residential part of the

villa.

The pars rustica was the commercial part, where the work – usually

farming –

was done. This distinction is very difficult to make in Dutch villae.

Often no

more than a few buildings have been excavated at each site, so it is

difficult

to determine what purpose they would have served. Furthermore, the two

sides of

villa life were often not entirely separate. The main, residential,

building

might also have contained rooms that would be used for commercial

purposes, for

example.

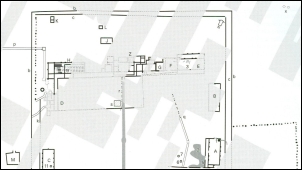

The large villa at Voerendaal

One

of the

most comprehensively excavated villae in the Netherlands is in

Voerendaal,

southern Limburg. Here, it is possible to distinguish between the pars

urbana and the pars rustica, although living

and working spaces do seem to have been combined here and there. The

pars

urbana consists of several separate buildings connected by a colonnade:

the

house in the north of the site, the horreum (granary) in the northwest,

the

bath house to the south of the horreum and, finally, the walled garden,

which

also formed a clear boundary between the pars domestica and pars

rustica. On

the northern side of the house, in the back yard, there were probably

two

shrines that can also be regarded as part of the pars domestica.

Another

slightly larger building whose function is unknown also stood here. The

location of the horreum – strongly associated with the commercial side

of the

villa – in the pars domestica can be explained by the fact that the

fruits of

an entire year’s labour would be stored there. The prosperity of the

villa

depended almost entirely on these stocks, so it was important that they

were

not accessible to all and sundry. The other buildings and structures at

the

front can be regarded as part of the pars rustica. The animal stalls or

barns

were probably on the eastern side. The staff of the villa might have

lived in

their own separate quarters close to the large house. In the southeast

corner

of the complex there was a building where grain was processed. The

smithy

probably stood in the southwest corner.

One

of the

most comprehensively excavated villae in the Netherlands is in

Voerendaal,

southern Limburg. Here, it is possible to distinguish between the pars

urbana and the pars rustica, although living

and working spaces do seem to have been combined here and there. The

pars

urbana consists of several separate buildings connected by a colonnade:

the

house in the north of the site, the horreum (granary) in the northwest,

the

bath house to the south of the horreum and, finally, the walled garden,

which

also formed a clear boundary between the pars domestica and pars

rustica. On

the northern side of the house, in the back yard, there were probably

two

shrines that can also be regarded as part of the pars domestica.

Another

slightly larger building whose function is unknown also stood here. The

location of the horreum – strongly associated with the commercial side

of the

villa – in the pars domestica can be explained by the fact that the

fruits of

an entire year’s labour would be stored there. The prosperity of the

villa

depended almost entirely on these stocks, so it was important that they

were

not accessible to all and sundry. The other buildings and structures at

the

front can be regarded as part of the pars rustica. The animal stalls or

barns

were probably on the eastern side. The staff of the villa might have

lived in

their own separate quarters close to the large house. In the southeast

corner

of the complex there was a building where grain was processed. The

smithy

probably stood in the southwest corner.

Central heating

Most

villae in

the Netherlands were not particularly luxurious. However, one luxury

people did

permit themselves was central heating. Traditional farmhouses were

heated by a

central hearth, which was also used for cooking. The animals in the

adjacent

stalls also provided some heat. In a villa, the rooms were heated by

the

hypocaust method. Warm air from a furnace room flowed through a hollow

space

under the floor (the hypocaust), rising from there through the wall

cavity. The

cavity was created using square or rectangular tubes (tubuli). Usually

only a

few rooms would be heated in this way. It is generally assumed that

these were

the living quarters or reception rooms. Bathrooms were usually also

heated.

Most

villae in

the Netherlands were not particularly luxurious. However, one luxury

people did

permit themselves was central heating. Traditional farmhouses were

heated by a

central hearth, which was also used for cooking. The animals in the

adjacent

stalls also provided some heat. In a villa, the rooms were heated by

the

hypocaust method. Warm air from a furnace room flowed through a hollow

space

under the floor (the hypocaust), rising from there through the wall

cavity. The

cavity was created using square or rectangular tubes (tubuli). Usually

only a

few rooms would be heated in this way. It is generally assumed that

these were

the living quarters or reception rooms. Bathrooms were usually also

heated.

Bath house

The bathing facility

in a villa was usually a smaller version of a public bath house. It

generally

consisted of cold, lukewarm and hot baths, a changing room and a

furnace room.

In Kerkrade-Holzkuil the bathing facility was found to be in a good

state of

preservation. Beside the furnace room was the hot water bath, and

probably also

a dining room or reception room, which would also be warmed by the heat

from

the hot bath. There was also an unheated room (probably the changing

room) and

a cold water bath. The bath house was surrounded by a corridor with a

door to

the outside, so that people from outside (probably staff) could use the

facilities without having to pass through the main building.

|

|

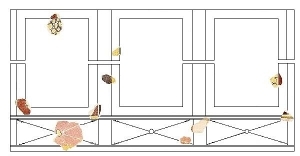

Wall paintings

The décor in a

Dutch villa was probably nothing special, though interior wall

paintings would

have clearly distinguished it from an indigenous farmhouse. Such

paintings were

otherwise found only in military or public buildings, or in town. Those

found

in the countryside were probably fairly simple and abstract. The walls

were

often divided into several framed panels of different colours. Ceilings

and

walls were sometimes decorated with a flower motif or rosettes. Many

fragments

of this kind of decoration have been found at the proto-villa in

Rijswijk. Few

remains of paintings depicting animals or people have ever been found,

except

in the villae at Kerkrade-Holzkuil and Maasbracht, where a number of

fragments

of wall paintings depicting people have been found. One of the people

depicted

at Maasbracht is shown with a writing tablet (tabella). The owner of

the villa

might have commissioned a portrait of himself to show that he was a

civilised

man with the ability to read and write.

|

|

|

Mosaics

Mosaics, generally so common in the Roman world, were rare in the Roman Netherlands. We know from reports of 19th-century excavations that some mosaics have been found, but none has been preserved. Individual mosaic pieces among the finds at several villa sites suggest that there were probably mosaics there, but we do not know what they would have looked like.

The importance of a good location

The

variety of

villae and villa-like settlements probably derives from the different

types of

soil and cultural traditions, and their geographical position within

the Roman empire. By far the majority of Dutch villae

were in the south of the present-day province of Limburg (represented

by orange

dots on the map). This was due primarily to the fertile soil found

there, which

would ensure the best possible yield. The loamy loess soil in the south

of

Limburg was fertile and easy to work. However, the locations of villae

suggest

that stockbreeding also played a role in the villa economy. Less

fertile ground

was fine for grazing cattle, and the wetter soils of a brook valley or

river

meadow provided perfect pasture. There were also slight differences in

fertility in the loess soils themselves. Villae often stood more or

less on the

dividing line between fertile and less fertile land, on a plateau or

slope down

towards a stream or river. This allowed crops to be grown on the dry,

fertile

soil, while cattle would graze the lower-lying wetter land. Besides the

favourable soil conditions at such a location, the aesthetics of the

landscape

might also have been a consideration. If a villa was built on a higher

spot, it

would be visible for miles around, certainly with its orange roof

tiles. And of

course the inhabitants of the villa would have a fantastic view.

The

variety of

villae and villa-like settlements probably derives from the different

types of

soil and cultural traditions, and their geographical position within

the Roman empire. By far the majority of Dutch villae

were in the south of the present-day province of Limburg (represented

by orange

dots on the map). This was due primarily to the fertile soil found

there, which

would ensure the best possible yield. The loamy loess soil in the south

of

Limburg was fertile and easy to work. However, the locations of villae

suggest

that stockbreeding also played a role in the villa economy. Less

fertile ground

was fine for grazing cattle, and the wetter soils of a brook valley or

river

meadow provided perfect pasture. There were also slight differences in

fertility in the loess soils themselves. Villae often stood more or

less on the

dividing line between fertile and less fertile land, on a plateau or

slope down

towards a stream or river. This allowed crops to be grown on the dry,

fertile

soil, while cattle would graze the lower-lying wetter land. Besides the

favourable soil conditions at such a location, the aesthetics of the

landscape

might also have been a consideration. If a villa was built on a higher

spot, it

would be visible for miles around, certainly with its orange roof

tiles. And of

course the inhabitants of the villa would have a fantastic view.

Infrastructure and markets

It was not

only the fertile loess soils that ensured the villa economy in southern

Limburg

flourished. Thanks to the road and water infrastructure, the loess area

and

Maas valley, in particular, were able to develop rapidly. There were

markets

close at hand, so produce could be sold quickly and at little cost.

Towns such