The

first mention of Thracia and the Thracians can be found in Homer. Later on,

the Father of History Herodotus writes (V, 64) about the Thracians that they

are one of the most numerous of peoples, after the Indian and the Scythian.

The Thracians were a combination of many tribes with close language and culture.

They were of Indo-European origin and populated the eastern part of the Balkans

from 3000 BC on. A significant number of scientific studies have been written

on their origin and territorial scope. The lands between the Lower Danube and

Moesians, Krobyzoi and Gaetae. The latter lived on the territory of present-day

north-east Bulgaria and the northern part of Dobrudja mountain in Romania.

The earliest data on Gaetae political union date back to 4th c. BC. Helis is marked as the centre of this union.

The

first mention of Thracia and the Thracians can be found in Homer. Later on,

the Father of History Herodotus writes (V, 64) about the Thracians that they

are one of the most numerous of peoples, after the Indian and the Scythian.

The Thracians were a combination of many tribes with close language and culture.

They were of Indo-European origin and populated the eastern part of the Balkans

from 3000 BC on. A significant number of scientific studies have been written

on their origin and territorial scope. The lands between the Lower Danube and

Moesians, Krobyzoi and Gaetae. The latter lived on the territory of present-day

north-east Bulgaria and the northern part of Dobrudja mountain in Romania.

The earliest data on Gaetae political union date back to 4th c. BC. Helis is marked as the centre of this union.  Some scholars assume that this Gaetae political centre, which is mentioned repeatedly

in historical sources, was located near the present-day village of Sboryanovo (northeast Bulgaria). The territory which was under the political control of

the Gaetae changed borders during the Hellenistic period. Generally, this territory

bordered to the east with the Black Sea, to the west – with the rivers Yantra

and Rossitsa, to the south it reached Haemus and to the north it was crossed

by the Lower Danube. The western border was quite mobile, and especially in

the decades before the Roman conquest it even reached the Iskar River valley.

Sources provide little information about the political structures on the territory

of present-day northwest Bulgaria. This zone, especially during the period

3rd – 2nd c. BC was home to active migration processes and its dynamics influenced the

study of the region. The Triballi settled here in 4th c. BC, to be pushed east by the Autariati and the Scordisci. In the next two

centuries the region was also settled by Celtic tribes, but the migration processes

probably continued. Thus, despite the large number of Thracian treasures from

the northwest Thracian territories, not one tribal or city centre is known

from there to this date.

Some scholars assume that this Gaetae political centre, which is mentioned repeatedly

in historical sources, was located near the present-day village of Sboryanovo (northeast Bulgaria). The territory which was under the political control of

the Gaetae changed borders during the Hellenistic period. Generally, this territory

bordered to the east with the Black Sea, to the west – with the rivers Yantra

and Rossitsa, to the south it reached Haemus and to the north it was crossed

by the Lower Danube. The western border was quite mobile, and especially in

the decades before the Roman conquest it even reached the Iskar River valley.

Sources provide little information about the political structures on the territory

of present-day northwest Bulgaria. This zone, especially during the period

3rd – 2nd c. BC was home to active migration processes and its dynamics influenced the

study of the region. The Triballi settled here in 4th c. BC, to be pushed east by the Autariati and the Scordisci. In the next two

centuries the region was also settled by Celtic tribes, but the migration processes

probably continued. Thus, despite the large number of Thracian treasures from

the northwest Thracian territories, not one tribal or city centre is known

from there to this date.  The state system in Thracia was established by the Odrysai who established a

powerful ruling dynasty and founded a state – the Odrysian kingdom - at the beginning of 5th c. BC. The head of the state was a king (or a great basileus) and he held the political,

military and religious powers, or he was a one-man ruler in the kingdom. The

throne was hereditary. The king ruled together with a family council (Thracians

– aristocrats, direct relatives) and close ones (other dynasties and strategists).

The whole political, legal and financial power was concentrated in the hands

of the king and his council. Characteristic of the Thracians, especially in

the period of the maturing of their state system, was that their kings – rulers

resided in different places. With time, however, the tribal centres acquired

elements of city culture. They were constructed on naturally protected terrains

and most often, on a terrain which was dominant in relation to the surroundings. The lands between the Lower Danube and Haemus and especially those in the eastern

part of the region were periodically and partially included in the Odrysian

kingdom, since the Gaetae were a very strong tribal formation. In 1982 a unique

in terms of its relief decoration with caryatids royal tomb was found near

the village of Sveshtari, next to the village of Sboryanovo, Isperih municipality . It has been declared a monument under the protection of UNESCO. The tomb is

an important indicator for the localization of a large tribal centre in the region . The latter has already been found at the archaeological site "Water station" and is systematically sudied.

The state system in Thracia was established by the Odrysai who established a

powerful ruling dynasty and founded a state – the Odrysian kingdom - at the beginning of 5th c. BC. The head of the state was a king (or a great basileus) and he held the political,

military and religious powers, or he was a one-man ruler in the kingdom. The

throne was hereditary. The king ruled together with a family council (Thracians

– aristocrats, direct relatives) and close ones (other dynasties and strategists).

The whole political, legal and financial power was concentrated in the hands

of the king and his council. Characteristic of the Thracians, especially in

the period of the maturing of their state system, was that their kings – rulers

resided in different places. With time, however, the tribal centres acquired

elements of city culture. They were constructed on naturally protected terrains

and most often, on a terrain which was dominant in relation to the surroundings. The lands between the Lower Danube and Haemus and especially those in the eastern

part of the region were periodically and partially included in the Odrysian

kingdom, since the Gaetae were a very strong tribal formation. In 1982 a unique

in terms of its relief decoration with caryatids royal tomb was found near

the village of Sveshtari, next to the village of Sboryanovo, Isperih municipality . It has been declared a monument under the protection of UNESCO. The tomb is

an important indicator for the localization of a large tribal centre in the region . The latter has already been found at the archaeological site "Water station" and is systematically sudied.

Gergana Kabakchieva

Chichikova, M. – Чичикова, М. Свещарската гробница - архитектура и декорация. – Terra Antiqua Balcanica III. София, 1988, 125 – 143.

Danov, Hr. – Данов, Хр. Древна Тракия. София, 1968.

Fol, Al. – Фол, Ал. Политическа история на траките от края на II хил. до V в.пр.н.е. София, 1972.

Fol, Al. – Фол Ал., Политика и култура в древна Тракия. София, 1990.

Fol, Al. – Фол. Ал., История на българските земи през Античността до края на III в.пр.н.е. София, 1997.

Fol, Al., Chicikova, M., Ivanov, Т., Teofilov, T. – The Thracian Tomb Near the Village of Sveshtari. Sofia, 1986.

Fol, Al., K.Jordanov, K.Poroyhanov, V.Fol. – Ancient Thrace, Sofia, 2000.

Gergova, D. – Гергова, Д. Сборяново. Свещената земя на гетите. София, 2004

History of Bulgaria ( edt. D.Kosev and o. ) - История на България, т. I, София, 1979.

Jordanov K. - Entstehung und Charakter des Staates bei den Thrakern. – Thracia 9, 31 – 52.

Marazov, I. – Маразов, И. За семантиката на изображенията в гробницата от Свещари. Изкуство, 1984, 4, 28 – 38.

Marazov, I. - Маразов, И. Древна Тракия, изд. ”Летера”, Пловдив, 2005.

Popov, Hr. – Попов, Хр. Урбанизация във вътрешните райони на Тракия и Илирия през VI - I век преди Христа. София, 2002.

Stoyanov, T. – Стоянов, Т. Тракийският град в Сборяново, София, 2000.

Velkov, V. – Велков, В. Античният живот в тракийските селища – Klio, 62, 1980, p. 5 sq.

In

the first millennium BC, on the territories between Lower Danube and Haemus,

a number of ancient Greek colonies developed along the west coast of the Black Sea, together with a certain number

of cities in the interior of Thracia.l. We can call the western part of the

Black Sea coast "the Thracian coast of Pontus Euxinus", since the region coincides with the concept Thracian coast of Ponta. The Thracians

were a significant part of the population in the territories of the ancient

Greek colonies and their territory. During the Hellenistic age, this region

was often under the political control of the Odrysian kingdom.

In

the first millennium BC, on the territories between Lower Danube and Haemus,

a number of ancient Greek colonies developed along the west coast of the Black Sea, together with a certain number

of cities in the interior of Thracia.l. We can call the western part of the

Black Sea coast "the Thracian coast of Pontus Euxinus", since the region coincides with the concept Thracian coast of Ponta. The Thracians

were a significant part of the population in the territories of the ancient

Greek colonies and their territory. During the Hellenistic age, this region

was often under the political control of the Odrysian kingdom.

The

earliest Greek colonies were founded in the last quarter of 7th c. BC from the city of Millet on the Asia Inferior coast of the Aegean Sea.

These are Histria (present-day ruins at the mouth of the Danube river, Romania). Tomis (Constanca,

Romania), Odessos (Varna, Bulgaria) and Apollonia (present-day Sozopol, Bulgaria).

The other colonies are Mesambria (Nessebar, Bulgaria), Anchialos (Pomorie), Dionisopolis (Balchik), Callatis

(Mangalia, Romania). These were Ionic colonies with the status of cities-poleis.

It is important to mention that the Thracian king Teres, the first ruler from

the Odrysian dynasty included in the territories of the Odrysian kingdom the

whole west Pontian coast from the mouth of the Danube to Abdera at the Aegean

shore. As the Greek historian Thucydides writes (II, 29, 1; 29, 5), the colonies

along the Aegean coast and those along the west coast of the Black Sea were

dependent on the Thracian kings and paid them tribute. During the Hellenistic

period these relations periodically fell into crisis but until the Roman Age

the region remained in close economic relations with the interior of Thracia.

The Odrysian kingdom was the one that provided different supplies of cattle,

timber, salted fish, wax, honey, wheat and slaves for Greece and the East Mediterranean

kingdoms through the ports of the west Pontian and Aegean cities. It covered a huge territory from the mouth of the Mesta river (Nestos)

at Abdera to the northeast up to the mouth of the Danube river (Thucydides,

II, 97,1).

The

earliest Greek colonies were founded in the last quarter of 7th c. BC from the city of Millet on the Asia Inferior coast of the Aegean Sea.

These are Histria (present-day ruins at the mouth of the Danube river, Romania). Tomis (Constanca,

Romania), Odessos (Varna, Bulgaria) and Apollonia (present-day Sozopol, Bulgaria).

The other colonies are Mesambria (Nessebar, Bulgaria), Anchialos (Pomorie), Dionisopolis (Balchik), Callatis

(Mangalia, Romania). These were Ionic colonies with the status of cities-poleis.

It is important to mention that the Thracian king Teres, the first ruler from

the Odrysian dynasty included in the territories of the Odrysian kingdom the

whole west Pontian coast from the mouth of the Danube to Abdera at the Aegean

shore. As the Greek historian Thucydides writes (II, 29, 1; 29, 5), the colonies

along the Aegean coast and those along the west coast of the Black Sea were

dependent on the Thracian kings and paid them tribute. During the Hellenistic

period these relations periodically fell into crisis but until the Roman Age

the region remained in close economic relations with the interior of Thracia.

The Odrysian kingdom was the one that provided different supplies of cattle,

timber, salted fish, wax, honey, wheat and slaves for Greece and the East Mediterranean

kingdoms through the ports of the west Pontian and Aegean cities. It covered a huge territory from the mouth of the Mesta river (Nestos)

at Abdera to the northeast up to the mouth of the Danube river (Thucydides,

II, 97,1).

One

of the most impressive among the west Pontian cities is the ancient Greek colony Odessos. The city was founded by citizens from Millet in Asia Inferior in 6th c. BC.

It was ruled by a city council (gr. βουλη) and a National Assembly (gr. δημος).

It expanded quickly and developed into a large city centre. In 6th – 5th c. BC it traded actively with Millet, Rodos, Hios, Samos, Tassos, and Athens.

In 4th c. BC Odessos prospered economically and culturally. Coins were minted here from the middle of 4th c. BC on ( Fig. 5 ) Phf02BG-html. The Odessos coins can be found far to the

west in the interior of the Thracian lands between the Lower Danube and Haemus

and this clearly shows the trade and exchange routes within the region in question.

The Romans appeared in Odessos in 72/71 BC when Marcus Lucullus, the ruler of province Macedonia undertook his campaign to the west coast of

the Black Sea and ravaged the Greek colony Apolonia (Sozopol). There is no

direct evidence about Odessos’s fate from those times but probably the city

was not affected by the Roman attacks. A little later the Roman armies attacked

another Greek colony, Histria, at the mouth of the Danube River. Thus, the

settlement of the Romans in the region of the west Black Sea dates back to

the middle or second half of 1st c. BC, most probably after the campaigns of Marcus Lucinius Crassus in 29 and 28 BC. Initially the west Pontian cities were attached to province

Macedonia and had the status of civitates föderatä, which meant that these economically important centres preserved their independent

internal city government and no Roman military units were located there. When

the Moesia province was founded in 12 – 15 AD, the Black Sea city union was

transferred administratively to the Moesia province and remained within it

until the end of 3rd c. AD.

One

of the most impressive among the west Pontian cities is the ancient Greek colony Odessos. The city was founded by citizens from Millet in Asia Inferior in 6th c. BC.

It was ruled by a city council (gr. βουλη) and a National Assembly (gr. δημος).

It expanded quickly and developed into a large city centre. In 6th – 5th c. BC it traded actively with Millet, Rodos, Hios, Samos, Tassos, and Athens.

In 4th c. BC Odessos prospered economically and culturally. Coins were minted here from the middle of 4th c. BC on ( Fig. 5 ) Phf02BG-html. The Odessos coins can be found far to the

west in the interior of the Thracian lands between the Lower Danube and Haemus

and this clearly shows the trade and exchange routes within the region in question.

The Romans appeared in Odessos in 72/71 BC when Marcus Lucullus, the ruler of province Macedonia undertook his campaign to the west coast of

the Black Sea and ravaged the Greek colony Apolonia (Sozopol). There is no

direct evidence about Odessos’s fate from those times but probably the city

was not affected by the Roman attacks. A little later the Roman armies attacked

another Greek colony, Histria, at the mouth of the Danube River. Thus, the

settlement of the Romans in the region of the west Black Sea dates back to

the middle or second half of 1st c. BC, most probably after the campaigns of Marcus Lucinius Crassus in 29 and 28 BC. Initially the west Pontian cities were attached to province

Macedonia and had the status of civitates föderatä, which meant that these economically important centres preserved their independent

internal city government and no Roman military units were located there. When

the Moesia province was founded in 12 – 15 AD, the Black Sea city union was

transferred administratively to the Moesia province and remained within it

until the end of 3rd c. AD.

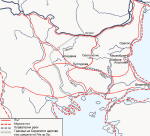

A

limited number of cities have been studied archaeologically in the interior

of pre-Roman Thracia, which was later included in the provinces Moesia Superior

and Moesia Inferior. This does not mean that there were no such cities. Some

of the centres of the local population had urban elements as early as 6th c. BC. They occupied a central location among the other forms of settlements.

No city functions can be found in the other settlements. They are distinguished

from the surrounding settled areas in terms of their structure of construction,

architecture and principles of organization of life. In addition, they had

a leading government role with regard to the other forms of settlement. From

the map it becomes clear that the number of cities in pre-Roman Thracia is far from small. (Fig. 6) MapIIBG01 – html. Many more of them are known in

the southern Thracian territories than in the region between the Carpathians

and Haemus (Stara planina), where there are archaeological data only about

three settlements with indications of a city. These are Cotofeni din Dos, in

Romania, the Thracian Gaetae centre near Sboryanovo village in northeast Bulgaria

and the Shumen fortress

A

limited number of cities have been studied archaeologically in the interior

of pre-Roman Thracia, which was later included in the provinces Moesia Superior

and Moesia Inferior. This does not mean that there were no such cities. Some

of the centres of the local population had urban elements as early as 6th c. BC. They occupied a central location among the other forms of settlements.

No city functions can be found in the other settlements. They are distinguished

from the surrounding settled areas in terms of their structure of construction,

architecture and principles of organization of life. In addition, they had

a leading government role with regard to the other forms of settlement. From

the map it becomes clear that the number of cities in pre-Roman Thracia is far from small. (Fig. 6) MapIIBG01 – html. Many more of them are known in

the southern Thracian territories than in the region between the Carpathians

and Haemus (Stara planina), where there are archaeological data only about

three settlements with indications of a city. These are Cotofeni din Dos, in

Romania, the Thracian Gaetae centre near Sboryanovo village in northeast Bulgaria

and the Shumen fortress

As

an example of a Thracian city we will review the one from the site "Water station" near Sboryanovo village, with the probable name of Helis or Dausdava. It is assumed that this was the Gaetae capital of Dromichaetes, the victor

of Lizimah. It was located on a plateau, naturally protected on three sides

by a river and steep shores. During the second half of 4th c. BC the city was fortified with a massive wall. Its territory was about 10 hectares and it enclosed a triangular space. Walls

were built across the fortress wall and along the slope, which blocked the

hill from the valley. The construction was implemented with coarsely processed

stones kept together with clay. According to the researchers, the clay was

baked during its sequential laying in layers. This construction technique is

defined as local and is significantly different from the construction of the

fortifications in the ancient Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast. Near

the southern gate there was a temple of the goddess Artemis-Phosphorus, protector

of the cities. The central part of the fortified area was occupied by streets

and houses. Different crafts developed in the city: metal working, pottery,

bone items. Helis maintained trade relations with the cities along the west

coast of the Black Sea, as well as with many of the centres in the East Mediterranean

and Greece – the islands of Tassos, Rhodos, Koss, and Attica. There was a mint for making coin imitations. The biggest Gaetae cult centre was

near the city. It was about 40km to the south of the Danube River and 120km

away from the Black Sea. It was located in a very beautiful area and united

a number of cult sites, fenced with walls, as well as sanctuaries. Some of

them were cut into the rock reefs of the hilly plain. The city was destroyed

by a strong earthquake around the middle of 3rd c. BC. Probably the earthquake also marks the fall of many of the west-Pontian

cities-poleis, as well as of other Thracian cities.

As

an example of a Thracian city we will review the one from the site "Water station" near Sboryanovo village, with the probable name of Helis or Dausdava. It is assumed that this was the Gaetae capital of Dromichaetes, the victor

of Lizimah. It was located on a plateau, naturally protected on three sides

by a river and steep shores. During the second half of 4th c. BC the city was fortified with a massive wall. Its territory was about 10 hectares and it enclosed a triangular space. Walls

were built across the fortress wall and along the slope, which blocked the

hill from the valley. The construction was implemented with coarsely processed

stones kept together with clay. According to the researchers, the clay was

baked during its sequential laying in layers. This construction technique is

defined as local and is significantly different from the construction of the

fortifications in the ancient Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast. Near

the southern gate there was a temple of the goddess Artemis-Phosphorus, protector

of the cities. The central part of the fortified area was occupied by streets

and houses. Different crafts developed in the city: metal working, pottery,

bone items. Helis maintained trade relations with the cities along the west

coast of the Black Sea, as well as with many of the centres in the East Mediterranean

and Greece – the islands of Tassos, Rhodos, Koss, and Attica. There was a mint for making coin imitations. The biggest Gaetae cult centre was

near the city. It was about 40km to the south of the Danube River and 120km

away from the Black Sea. It was located in a very beautiful area and united

a number of cult sites, fenced with walls, as well as sanctuaries. Some of

them were cut into the rock reefs of the hilly plain. The city was destroyed

by a strong earthquake around the middle of 3rd c. BC. Probably the earthquake also marks the fall of many of the west-Pontian

cities-poleis, as well as of other Thracian cities.

There are still no certain archaeological data about the cities in the interior of Thracia between the Danube and Haemus. The reason for this is not only the limited archaeological studies, but also the great dynamics of migration in the region in the period between 3rd and 1st c. BC.

Thus, when the Romans arrived in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula, they found cities along the west coast of the Black Sea and in the interior of Thracia. Two types of cities can be distinguished in terms of their architecture and structure – the Greek colonies and the cities-centres of the local population – but both fell into decline at the beginning of the Roman conquest of the Balkans and the formation of the Roman provinces.

Gergana Kabakchieva

Chichikova, M. – Чичикова, М. Свещарската гробница - архитектура и декорация. – Terra Antiqua Balcanica III. София, 1988, 125 – 143.

Danov, Hr. – Данов, Хр. Древна Тракия. София, 1968.

Fol, Al. – Фол, Ал. Политическа история на траките от края на II хил. до V в.пр.н.е. София, 1972.

Fol, Al. – Фол Ал., Политика и култура в древна Тракия. София, 1990.

Fol, Al. – Фол. Ал., История на българските земи през Античността до края на III в.пр.н.е. София, 1997.

Fol, Al., Chicikova, M., Ivanov, Т., Teofilov, T. – The Thracian Tomb Near the Village of Sveshtari. Sofia, 1986.

Fol, Al., K.Jordanov, K.Poroyhanov, V.Fol. – Ancient Thrace, Sofia, 2000.

Gergova, D. – Гергова, Д. Сборяново. Свещената земя на гетите. София, 2004

History of Bulgaria ( edt. D.Kosev and o. ) - История на България, т. I, София, 1979.

Isaak, B. – The Greek Settlements in Thrace until the MacedinianConquest. Brill. Leiden, 1986.

Jordanov K. - Entstehung und Charakter des Staates bei den Thrakern. – Thracia 9, 31 – 52.

Marazov, I. – Маразов, И. За семантиката на изображенията в гробницата от

Свещари. Изкуство, 1984, 4, 28 – 38.

Marazov, I. - Маразов, И. Древна Тракия, изд. ”Летера”, Пловдив, 2005.

Popov, Hr. – Попов, Хр. Урбанизация във вътрешните райони на Тракия и Илирия през VI - I век преди Христа. София, 2002.

Stoyanov, T. – Стоянов, Т. Тракийският град в Сборяново, София, 2000.

Velkov, V. – Велков, В. Античният живот в тракийските селища – Klio, 62, 1980, p. 5 sq.

If we exclude the Greek cities on the Black Sea coast with their most common legal status of civitates stipendiariae, evidence of other civitates

in the two provinces, Upper and Lower Moesia, is vestigial at best. The tribal situation at the beginning

of Roman rule is reflected most fully in the words of Pliny the Elder (III 149): “Adjoining Pannonia is the province called Moesia, which runs

with the course of the Danube right down to the Black Sea, beginning at the confluence of the Danube and the Save mentioned above. Moesia contains the Dardani,

Celegeri, Triballi, Timachi, Moesi, Thracians and Scythians adjacent to the

Black Sea.” (Pannoniae iungitur provincia, quae Moesia appellatur,

ad Pontum usque cum Danuvio decurrens. incipit a confluente supra dicto. in

ea Dardani, Celegeri, Triballi, Timachi, Moesi Thraces Pontoque contermini Scythae).

Ptolemy was much less specific when speaking of the peoples inhabiting the two

Moesias (III 9,2): he mentioned the Tricornenses near modern Belgrade, the Moesi

on the Ciabrus river, the Picenses east of Viminacium (present day Kostolac)

and the Dardani near the border with Macedonia.To the east of the Moesi

(III 10, 9-10) he listed the Dimenses, Appiarenses, Utenses, with whom the localities

of Dimum, Appiaria and Utus should be linked respectively; near Odessos and

Dionysopolis he located the tribe (civitas ?) of the Krobyzi, in Dobrogea

the Troglodytae and Peucini.

Neither Pliny the Elder nor Ptolemy commented on the legal status of the organization

of these tribes. It may have been an echo of an ethnic division, that is, a

division of the province into civitates stipendiariae. It does not

follow from Ptolemy’s expression “Ratiaria of the Moesi” (III

9, 3) and “Oescus of the Triballi” (III 10, 5) that legal status

is involved. The later municipia Celegerorum in Pannonia and Dardanorum in

Upper Moesia constitute better evidence, as they developed in the territories

of these tribes.

Oescus was the same for civitas Treballiae. While there is no

later data about these two civitates, it is difficult to believe that

they simply disappeared despite both Ratiaria and

Oescus being raised to the rank of Roman cities (coloniae).

This also concerns the tribes mentioned by Pliny and Ptolemy, which may have

all been included under a later designation Thraces, as, for example,

in the action of separating the territory of the city of Odessos (modern Varna)

from that of the Thracian tribe(s)?: f(ines) terr(ae) Thrac(um) and

f(ines) terr(ae) Odess(itanorum). The survival of some of the civitates

mentioned by Ptolemy appears to be confirmed by the place names of localities

formed from the

Oescus was the same for civitas Treballiae. While there is no

later data about these two civitates, it is difficult to believe that

they simply disappeared despite both Ratiaria and

Oescus being raised to the rank of Roman cities (coloniae).

This also concerns the tribes mentioned by Pliny and Ptolemy, which may have

all been included under a later designation Thraces, as, for example,

in the action of separating the territory of the city of Odessos (modern Varna)

from that of the Thracian tribe(s)?: f(ines) terr(ae) Thrac(um) and

f(ines) terr(ae) Odess(itanorum). The survival of some of the civitates

mentioned by Ptolemy appears to be confirmed by the place names of localities

formed from the

names

of the tribes: Dimum, Utus, Appiaria. This could refer particularly to

Dimum, which was likely the main locality of the civitas Dimensium,

situated Weast of colonia Oescus . A list of praetorians

of AD 241 contains the names of as many as 16 soldiers originating from the regio

(= civitas ?) Dimensis. Civitas Naissatum mentioned in an inscription

of the late fourth century is to my mind simply another way of referring to

the town and has nothing to do with the concept of a tribal civitas.

names

of the tribes: Dimum, Utus, Appiaria. This could refer particularly to

Dimum, which was likely the main locality of the civitas Dimensium,

situated Weast of colonia Oescus . A list of praetorians

of AD 241 contains the names of as many as 16 soldiers originating from the regio

(= civitas ?) Dimensis. Civitas Naissatum mentioned in an inscription

of the late fourth century is to my mind simply another way of referring to

the town and has nothing to do with the concept of a tribal civitas. The vici , especially in Lower

Moesia, could possibly be a reflection of earlier attempts to organize the province

into a system of civitates; it is indeed to some extent a

specificity of this province.

The vici , especially in Lower

Moesia, could possibly be a reflection of earlier attempts to organize the province

into a system of civitates; it is indeed to some extent a

specificity of this province.

Ostrite Mogili

|

municipium status

|

Some of them (Ostrite Mogili , Ostrov, Noviodunum)

were granted municipium status with time,

but others retained their original structure.

The vici Quintionis and Secundini from

Dobrogea are the most characteristic. They are situated in the territory

of the town of Histria and inhabited by veterani et cives Romani et Bessi

consistentes (military settlers and settlers with Roman citizenship and

the Bessi) - v. Quintionis, or cives Romani et Lai consistentes (settlers

with Roman citizenship and the Lai) - v. Secundini. It is this combination that

determines the specificity of the two vici. The Bessi and Lai are Thracian

tribes, displaced at the end of the old era, and resettled together with the

above-mentioned Ausdecenses in the territories of Moesia (Lower). It is not

to be excluded that initially they, too, like the Ausdecenses, were organized

in the form of one or two civitates. This structure could have proved

impermanent due to the intensive flow of Roman settlers

to the province. Relatively substantial epigraphic records permit a look

at the specific nature of the relation between Roman citizens and the Bessi

and Lai: both supplied candidates for various offices with the reservation that

the position of questor responsible for finances was prohibited to

the peregrini.

The vici Quintionis and Secundini from

Dobrogea are the most characteristic. They are situated in the territory

of the town of Histria and inhabited by veterani et cives Romani et Bessi

consistentes (military settlers and settlers with Roman citizenship and

the Bessi) - v. Quintionis, or cives Romani et Lai consistentes (settlers

with Roman citizenship and the Lai) - v. Secundini. It is this combination that

determines the specificity of the two vici. The Bessi and Lai are Thracian

tribes, displaced at the end of the old era, and resettled together with the

above-mentioned Ausdecenses in the territories of Moesia (Lower). It is not

to be excluded that initially they, too, like the Ausdecenses, were organized

in the form of one or two civitates. This structure could have proved

impermanent due to the intensive flow of Roman settlers

to the province. Relatively substantial epigraphic records permit a look

at the specific nature of the relation between Roman citizens and the Bessi

and Lai: both supplied candidates for various offices with the reservation that

the position of questor responsible for finances was prohibited to

the peregrini.

Outside the vici Secundini and Quintionis we encounter the ethnic duality of

the cives Romani et Bessi consistentes also in vicus Ulmetum, which

was administratively subject to the civitas Capidavensis, and the cives

et Lai consistentes in vicus Turris Muca(poris ?) in the territory of Tomis.

Still other vici, assigned administratively to different cities, are

confirmed in Dobrogean territory. Situated in the territory of Capidava were

vicus Scenopensis and vicus HI…(modern Dorobantul); vicus Clementianensis

(modern Mihail Kogalniceanu) and vicus Narcissiani and the more or less undefined

vicus S.C…IA (modern Palazu) were in the territory of Tomis. Confirmed

near Histria were vici Celeris and Buteridavensis. North of Capidava there was

vicus Vergobrittiani (Gîrliciu?), the name of which is a clear reference

to Celtic settlement. Vicus I Urb…, inhabited by the cives Romani

consistentes, was localized in the area of present-day Medgidia. From northern

Dobrogea we have vicus Petra (modern Camena) and vicus Novus (Babadag), whose

inhabitants were referred to as c(ives) R(omani) v(eterani) et viconovenses.

This last term should be understood as referring to the local Thracian population,

cohabiting with Roman citizens.

From Noviodunum we have information about two vici, one of unknown

name, most likely in the territory of the modern village of Niculitel (?),and

another one, situated near the locality of Independenta, which was referred

to in the sources as a vicus classicorum, whose inhabitants were cives Romani

consistentes. The status of vicus should undoubtedly be assigned to Troesmis

prior to it being granted municipal status, and it is not to be excluded that

it was the capital of the civitas Troesmensium.

Information

about vici outside Dobrogea is scarce at the very

least. One should mention first of all those situated in western Lower Moesia:

vicus Trullensium, near the modern village of Kunino, in the upper run of the

river Iskar, vicus Tautiomosis in the present-day locality of Krivodol, governed

by Aurelius Victorinus Victoris (filius), princeps vici, vicus Vorovum

minor (modern Krawoder) and vicus Siamus (modern Kadim on the Danube, west of

Oescus).

Not always are we able to determine the actual status of vici, nonetheless,

there is no doubt that in the realities of the province of Moesia they provided

a place for the local Thracian population to mix with settlers arriving from

other parts of the Roman Empire. Neither can it be excluded that some of them

at least echoed an earlier administrative division into territoria civitatium,

a division that would go back to the beginnings of Roman rule in the province.

Information

about vici outside Dobrogea is scarce at the very

least. One should mention first of all those situated in western Lower Moesia:

vicus Trullensium, near the modern village of Kunino, in the upper run of the

river Iskar, vicus Tautiomosis in the present-day locality of Krivodol, governed

by Aurelius Victorinus Victoris (filius), princeps vici, vicus Vorovum

minor (modern Krawoder) and vicus Siamus (modern Kadim on the Danube, west of

Oescus).

Not always are we able to determine the actual status of vici, nonetheless,

there is no doubt that in the realities of the province of Moesia they provided

a place for the local Thracian population to mix with settlers arriving from

other parts of the Roman Empire. Neither can it be excluded that some of them

at least echoed an earlier administrative division into territoria civitatium,

a division that would go back to the beginnings of Roman rule in the province.

- M. Barbulescu, Viata rurala în Dobrogea romana (sec. I-III p. Chr.),

Constanta 2001

- A. Barnea, Municipium Noviodunum. Nouvelles données épigraphiques,

Dacia 32, 1988, 53-60

- I. Barnea, R. Vulpe, Din Istoria Dobrogei, II. Romanii la Dunarea de Jos,

Bucuresti 1968

- E. Dorutiu-Boila, Castra legionis V Macedonicae und Municipium Troesmense,

Dacia 16, 1972, 133-144

- E. Dorutiu-Boila, Territoriul militar al legiunii V Macedonica la Dunarea

de Jos, Studii si Cercetari de Istorie Veche 23, 1972, 45-62

- Gr. Florescu, R. Florescu, P. Diaconu, Capidava, Bucuresti 1958

- B. Gerov, Beiträge zur Geschichte der römischen Provinzen Moesien

und Thrakien. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Amsterdam 1980

- B. Gerov, Landownership in Roman Thracia and Moesia (1st-3rd century), Amsterdam

1988

- J. Kolendo, Miasta i terytoria plemienne w prowincji Mezji Dolnej w okresie

wczesnego Cesarstwa, w: Prowincje rzymskie i ich znaczenie w ramach Imperium,

Wroclaw 1976, 45-68

- J. Kolendo, La relation ville/campagne dans les provinces danubiennes. Réalité et

son reflet dans la mentalité, Ländliche Besiedlung und Landwirtschaft

in den Rhein-Donau-Provinzen des Römischen Reiches, Passau (= Passauer

Schriften zur Archäologie 2)

- S. Lambrino, Le vicus Quintionis et le vicus Secundini, Mélanges Marouzeau,

Paris 1948, 320-346

- S. Lambrino, Traces épigraphiques de centuriation romaine en Scythie

Mineure (Roumanie), [in:] Hommages à Albert Grenier, Bruxelles 1962,

934-939

- M. Mirkovic, Einheimische Bevölkerung und römische Städte

in der Provinz Obermösien, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen

Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 811 - 848

- A. Mócsy, Gesellschaft und Romanisation in der römischen Provinz

Moesia Superior, Budapest 1970

- A. Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, London-Boston 1974

- L. Mrozewicz, Rozwój ustroju municypalnego a postepy romanizacji w

Mezji Dolnej, Poznan 1982

- L. Mrozewicz, Arystokracja municypalna w rzymskich prowincjach nad Renem

i Dunajem, Poznan 1989

- L. Mrozewicz, Die Veteranen in den Munizipalräten an Rhein und Donau

zur Hohen Kaiserzeit (I.-III. Jahrhundert), Eos 77, 1989, 65-80

- M. Munteanu, Cu privire la organizarea satesti din Dobrogea romana, Pontica

4, 1971, 125-136

- V. Pârvan, Începuturile vietii romane la gurile Dunarii, Bucuresti2

1974

- A.G. Poulter, Rural Communities (Vici and komai) and Their Role in the Organization

of the Limes of Moesia Inferior, Roman Frontier Studies 1979 (= British Archaeological

Reports. Intern. Series 71 III), Oxford 1980, 729 -743

- A. Suceveanu, M. Zahariade, Un nouveau ‘vicus’ sur la territoire

de la Dobroudja romaine, Dacia 30, 1986, 109-120

- A. Suceveanu, A. Barnea, La Dobroudja romaine, Bucarest 1991

- I. Velkov, Vicus Trullensium, [w:] Studia in honorem D. Decev, Sofia 1958,

556-557

- V. Velkov, Kam voprosa za agrarnite otnošenija v Mizija pres II V. na

n.e., Arheologija 4, 1962, 31-34

- V. Velkov, Roman Cities in Bulgaria. Collected Studies, Amsterdam 1980

- V. Velkov, Civitas Bessica Diniscorta in Moesia Inferior, Studia in honorem

B. Gerov, Sofia 1990, 253-258

- F. Vittinghof, Die Bedeutung der Legionslager für die Entstehung der

römischen Städte an der Donau und in Dakien, Festschrift R. Jankuhn,

Neumünster 1968, 132-142

- F. Vittinghoff, Die rechtliche und soziale Stellung der canabae legionis

und die Herkunftangabe castris, Chiron 1, 1971, 301-308

- F. Vittinghof, Zur römischen Municipalisierung des lateinischen Donau-Balkanraumes.

Methodische Bemerkungen, Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt, II

6, Berlin-New York 1977, 3-51

- R. Vulpe, Canabenses si Troesmenses, Studii si Cercetari de Istorie Veche

4, 1953, 557-582

- R. Vulpe, Colonies et municipes de la Mésie Inférieure, w:

idem, Studia Thracologica, Bucuresti 1976, 289-314

- E. Zah, A. Suceveanu, Bessi consistentes, Studii si Cercetari de Istorie

Veche 22, 2, 1971, 567-578

The issue of determining the population of the various

civitates in Moesian provinces holds a significant place in all

research on ethnic relations in the provinces, as well as more generally, on

the relations between the local population

and Roman settlers. Sources are vestigial at best, allowing for little more

than a collective, in the sense of ethnic definition of the inhabitants: civitas

Moesiae (Moesi), civitas Treballiae (Triballi), civitas Ausdecensium (Ausdecenses),

Bessi consistentes, Lai consistentes, Tricornenses, Daci, Thraces. These

names demonstrate the complexity of the tribal relations in the region in question,

but they lead to no detailed, that is, individual conclusions. They may also

reflect the fact that in later times, once Roman structures had solidified in

the province, native inhabitants did not identify their origins (their „small

homeland”) with the civitas, but rather with specific localities: municipalities

(coloniae, municipium) and villages

(vici ), where they had their roots. Therefore,

it is to be assumed that vici not in municipale or colonia territory must have

belonged to some civitates. Consequently, the demographic structure of the civitates,

at least to a certain extent, was made up of the inhabitants of these vici.

The issue of determining the population of the various

civitates in Moesian provinces holds a significant place in all

research on ethnic relations in the provinces, as well as more generally, on

the relations between the local population

and Roman settlers. Sources are vestigial at best, allowing for little more

than a collective, in the sense of ethnic definition of the inhabitants: civitas

Moesiae (Moesi), civitas Treballiae (Triballi), civitas Ausdecensium (Ausdecenses),

Bessi consistentes, Lai consistentes, Tricornenses, Daci, Thraces. These

names demonstrate the complexity of the tribal relations in the region in question,

but they lead to no detailed, that is, individual conclusions. They may also

reflect the fact that in later times, once Roman structures had solidified in

the province, native inhabitants did not identify their origins (their „small

homeland”) with the civitas, but rather with specific localities: municipalities

(coloniae, municipium) and villages

(vici ), where they had their roots. Therefore,

it is to be assumed that vici not in municipale or colonia territory must have

belonged to some civitates. Consequently, the demographic structure of the civitates,

at least to a certain extent, was made up of the inhabitants of these vici.

Even

so, we cannot avoid collective definitions, starting with

toponymic designations, such as vicani Viconovenses (from vicus

Novus), vicani Petrenses (from vicus Petra), vicani Trullenses

(from vicus Trullensium), Troesmenses or simply vicani. Coupled

with these are occasionally “professional” designations, such as,

for example, vicus Classicorum (from classici, i.e., related

to the fleet) and to some extent the veterans. Complementing this picture are

the settlers with Roman citicenship (cives Romani consistentes), occurring

either alone or in combination with other groups. In the latter case, the emphasis

is distinctly on the legal and political status of possessors of civitas

Romana, because concepts like veterani or, for example, Troesmenses must

have encompassed Roman citizens as well. The opposite equally cannot be excluded:

ex-soldiers (veterani), Roman citizens, most certainly would have wanted

to emphasize their status (superiority ?) precisely in the milieu of cives Romani.

Even

so, we cannot avoid collective definitions, starting with

toponymic designations, such as vicani Viconovenses (from vicus

Novus), vicani Petrenses (from vicus Petra), vicani Trullenses

(from vicus Trullensium), Troesmenses or simply vicani. Coupled

with these are occasionally “professional” designations, such as,

for example, vicus Classicorum (from classici, i.e., related

to the fleet) and to some extent the veterans. Complementing this picture are

the settlers with Roman citicenship (cives Romani consistentes), occurring

either alone or in combination with other groups. In the latter case, the emphasis

is distinctly on the legal and political status of possessors of civitas

Romana, because concepts like veterani or, for example, Troesmenses must

have encompassed Roman citizens as well. The opposite equally cannot be excluded:

ex-soldiers (veterani), Roman citizens, most certainly would have wanted

to emphasize their status (superiority ?) precisely in the milieu of cives Romani.

As for vici, fortunately, sources provide us with information about

specific persons as well. More importantly, these are individuals of local origins,

not always having Roman citizen status or else having been granted such status

only recently. The most instructive in this respect are the vici from Dobrogean

territory Najbardziej instruktywnie jawia nam sie vici z terenów

Dobrudzy, demonstrating as they do very clearly the coexistence between

the local population and Roman citizens. Listed among the Roman names are ones

that are typically Thracian, like Derzenus Aulupori, Bizienis, Durisses

Bithi, Genicius Brini, Dotu Zinebti, Mucatralus Doli, Valerius Cutiunis, Derzenus

Biti, Artemias Discoridentis, Valerius Cosenis and a number of others.

It is also beyond doubt that recruits for the auxiliary troops were taken from

the local tribes (meaning from the territory of

both Moesias). The best proof of this is provided by military diplomas giving

the names of both retiring soldiers and frequently their families (legalized

by the diploma). A classic case from Upper Moesia is Doroturma Dotochae

fil(ia) Tricorn(ensi), that is, from the Tricornenses tribe. Another

example is Bithus Solae f(ilius) Bessus from the well-known diploma

of Palamarcia (Moesia Inferior), although there is no way of telling whether

he came from the Bessi settled in Dobrogea or from the Rhodope mountains.

The discovery of the diploma in northern Bulgaria and its date (November 13,

AD 140) makes the former possibility a likely one. Also Seuthus […]is

f(ilius) Scaen(us), appearing in a diploma from the time of Domitian, could

have come from a local (that is, living in Lower Moesia) tribe of the Skaioi,

whose seat has been localized on the Danube west of Novae. It cannot be excluded

that the Seuthus came here from the Propontis, where a tribe of the

Skaioi is also evidenced.

There can be no doubt, however, that the local tribes interacted with Roman

settlers arriving in the provinces. By this, they contributed to the creation,

to a smaller or larger extent, of a demographically new class, referred to by

the name of the province.

Meriting

attention in this context is a list of praetorians of AD 241, containing the

names of as many as 16 soldiers originating from the regio (= civitas ?)

Dimensis. One of them bore the gentilicium Iulius, six were Aurelii,

and one other had the typical Roman family name of Sulpicius. The rest betray

Thracian provenance. The list is an excellent example of deeply rooted processes

of Romanization, demonstrating at the same time how military service had become

a sure path to social advancement for the inhabitants of Upper and Lower Moesia.

In the opinion of Borys Gerov, these soldiers, obviously of native origins,

had served in the legio I Italica in Novae

before being transferred to the praetorians in Rome. Antonius Paterio of the

X praetorian cohort came from the vicus C[e]niscus in the territory of Ratiaria

in Upper Moesia, Aurelius son of Mucconius (Aurelius Mucconi), who referred

to himself as a Moesian (civis Mesacus – sic !), gave vicus Pereprus in

the territory of Melta (? civis Meletinus) as his birthplace. Despite

the scarcity of information and their randomness, the sources on vicus demographics,

covering, after all, a period of a few hundred years, illustrate the fascinating

process of merging, like in a crucible, of native inhabitants and settlers coming

in from all corners of the Empire. The outcome of this process was a class of

inhabitants, which saw its group identity, regardless of individual ethnicity,

in the territory, the province in this case. An excellent example of this are

the cited designations of Moesiacus and civis Moesiacus.

Meriting

attention in this context is a list of praetorians of AD 241, containing the

names of as many as 16 soldiers originating from the regio (= civitas ?)

Dimensis. One of them bore the gentilicium Iulius, six were Aurelii,

and one other had the typical Roman family name of Sulpicius. The rest betray

Thracian provenance. The list is an excellent example of deeply rooted processes

of Romanization, demonstrating at the same time how military service had become

a sure path to social advancement for the inhabitants of Upper and Lower Moesia.

In the opinion of Borys Gerov, these soldiers, obviously of native origins,

had served in the legio I Italica in Novae

before being transferred to the praetorians in Rome. Antonius Paterio of the

X praetorian cohort came from the vicus C[e]niscus in the territory of Ratiaria

in Upper Moesia, Aurelius son of Mucconius (Aurelius Mucconi), who referred

to himself as a Moesian (civis Mesacus – sic !), gave vicus Pereprus in

the territory of Melta (? civis Meletinus) as his birthplace. Despite

the scarcity of information and their randomness, the sources on vicus demographics,

covering, after all, a period of a few hundred years, illustrate the fascinating

process of merging, like in a crucible, of native inhabitants and settlers coming

in from all corners of the Empire. The outcome of this process was a class of

inhabitants, which saw its group identity, regardless of individual ethnicity,

in the territory, the province in this case. An excellent example of this are

the cited designations of Moesiacus and civis Moesiacus.

- I. Barnea, R. Vulpe, Din Istoria Dobrogei, II. Romanii la Dunarea de Jos,

Bucuresti 1968

- M. Barbulescu, Viata rurala în Dobrogea romana (sec. I-III p. Chr.),

Constanta 2001

- B. Gerov, Romanizmat meždu Dunava i Balkana ot Hadrian do Konstantin

Veliki, Godišnik na Sofijskija Universitet, Filologiceski Fakultet XLVIII

1952/1953

- B. Gerov, Beiträge zur Geschichte der römischen Provinzen Moesien

und Thrakien. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Amsterdam 1980

- B. Gerov, Landownership in Roman Thracia and Moesia (1st-3rd century), Amsterdam

1988

- J. Kolendo, Témoignages épigraphiques de deux opérations

de bornage de territoires en Mésie Inférieure, Archeologia 26,

1975, 83-94

- J. Kolendo, Miasta i terytoria plemienne w prowincji Mezji Dolnej w okresie

wczesnego Cesarstwa, w: Prowincje rzymskie i ich znaczenie w ramach Imperium,

Wroclaw 1976, 45-68

- J. Kolendo, La relation ville/campagne dans les provinces danubiennes. Réalité et

son reflet dans la mentalité, Ländliche Besiedlung und Landwirtschaft

in den Rhein-Donau-Provinzen des Römischen Reiches, Passau (= Passauer

Schriften zur Archäologie 2)

- S. Lambrino, Le vicus Quintionis et le vicus Secundini, Mélanges Marouzeau,

Paris 1948, 320-346

- M. Mirkovic, Einheimische Bevölkerung und römische Städte

in der Provinz Obermösien, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen

Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 811 - 848

- A. Mócsy, Gesellschaft und Romanisation in der römischen Provinz

Moesia Superior, Budapest 1970

- A. Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, London-Boston 1974

- L. Mrozewicz, Rozwój ustroju municypalnego a postepy romanizacji w

Mezji Dolnej, Poznan 1982

- L. Mrozewicz, Arystokracja municypalna w rzymskich prowincjach nad Renem

i Dunajem, Poznan 1989

- L. Mrozewicz, Legionisci Mezyjscy w I wieku po Chrystusie [Mösische

Legionäre im 1. Jh. nach Christus], Poznan 1995

- C.C. Petolescu, A.T. Popescu, Ein neues Militärdiplom für die Provinz

Moesia Inferior (w druku)

- A.G. Poulter, Rural Communities (Vici and komai) and Their Role in the Organization

of the Limes of Moesia Inferior, Roman Frontier Studies 1979 (= British Archaeological

Reports. Intern. Series 71 III), Oxford 1980, 729 -743

- A. Suceveanu, M. Zahariade, Un nouveau ‘vicus’ sur la territoire

de la Dobroudja romaine, Dacia 30, 1986, 109-120

- A. Suceveanu, A. Barnea, La Dobroudja romaine, Bucarest 1991

- V. Velkov, Iz istorii nižnedunajskogo limesa v konce I v. n.e., Vestnik

Drevnej Istorii 1961, 2, 69-82

- V. Velkov, Roman Cities in Bulgaria. Collected Studies, Amsterdam 1980

- V. Velkov, Civitas Bessica Diniscorta in Moesia Inferior, Studia in honorem

B. Gerov, Sofia 1990, 253-258

- R. Vulpe, Canabenses si Troesmenses, Studii si Cercetari de Istorie Veche

4, 1953, 557-582

- R. Vulpe, Colonies et municipes de la Mésie Inférieure, w:

idem, Studia Thracologica, Bucuresti 1976, 289-314

- E. Zah, A. Suceveanu, Bessi consistentes, Studii si Cercetari de Istorie

Veche 22, 2, 1971, 567-578

A reconstruction of the world of religious beliefs of the population inhabiting

the civitates (that is, territorial-tribal

units) is extremely difficult, considering that the sources are modest at best.

The area in question was inhabited by a Thracian

(Geto-Thracian) peoples, whose beliefs have come down to us in some extent

thanks to the historians Herodotus (4, 93-94; 5, 2-6) and Cassius Dio (51, 25.5),

for example. The information, however, is not very extensive and refers to a

pre-Roman period, while the present discussion is of religious cults functioning

in the Roman provinces.

A reconstruction of the world of religious beliefs of the population inhabiting

the civitates (that is, territorial-tribal

units) is extremely difficult, considering that the sources are modest at best.

The area in question was inhabited by a Thracian

(Geto-Thracian) peoples, whose beliefs have come down to us in some extent

thanks to the historians Herodotus (4, 93-94; 5, 2-6) and Cassius Dio (51, 25.5),

for example. The information, however, is not very extensive and refers to a

pre-Roman period, while the present discussion is of religious cults functioning

in the Roman provinces.

The few pieces of information on the

civitates in the two Moesias , starting with the earliest one

connected with C. Baebius Atticus, who was praefectus civitatium Moesiae

et Treballiae, do little more than mention their existence. As for the

number and range of civitates,

we are doomed to conjecture. This is true of religious issues as well, because

in most cases it is impossible to determine whether epigraphical evidence of

a cult reflects the beliefs of the autochthonous population (which could have

been organized, at least in earlier times, as a civitas peregrine)

or those of a migrant group.Neither can we be certain that the civitates

Moesiae et Treballiae, which were already in existence for some time, survived

Trajan’s raising of Ratiaria and

The few pieces of information on the

civitates in the two Moesias , starting with the earliest one

connected with C. Baebius Atticus, who was praefectus civitatium Moesiae

et Treballiae, do little more than mention their existence. As for the

number and range of civitates,

we are doomed to conjecture. This is true of religious issues as well, because

in most cases it is impossible to determine whether epigraphical evidence of

a cult reflects the beliefs of the autochthonous population (which could have

been organized, at least in earlier times, as a civitas peregrine)

or those of a migrant group.Neither can we be certain that the civitates

Moesiae et Treballiae, which were already in existence for some time, survived

Trajan’s raising of Ratiaria and

Oescus

respectively to the status of Roman colonies. Therefore, the discussion below

is selective (two examples: Montana and Troesmis) and highly hypothetical.

Oescus

respectively to the status of Roman colonies. Therefore, the discussion below

is selective (two examples: Montana and Troesmis) and highly hypothetical.

Montana (regio Montanensium) in the western part of Lower Moesia,

most likely in the region of civitas Triballorum, can be deemed the most suggestive

example. The site and its neighbourhood has yielded an exceptional trove of

votive inscriptions dedicated to Dionysus, Epona, Hermes, Hercules, Heros,

Aesculapios (Asklepios), Hygieia, Aesculapios (Asklepios) and Hygieia, Silvanus,

Zeus and Hera. Also confirmed is the cult of Semele, Silvestris, Sarapis, Mercury,

Mars, Liber Pater and naturally Jupiter and Juno. But the greatest adoration

in Montana was enjoyed by the divine siblings Apollo and Diana. Archaeological

excavations have uncovered the remains of a temple of Diana and Apollo, possibly

the biggest Roman-period temple west of Oescus.

Several dozen altars with dedications to Diana, Apollo or both collectively

and impressive remains of statuary were discovered. The cross-section through

dedicating parties is relatively broad. Predominant among them are persons

connected with the army, a fact resulting from the garrisoning of military

units in Montana. Also present, albeit seldom, are the names of civilians: Macrinus,

Hilarus, Vitelius, Tib. Claudius Vitulus, Claudius Constans, Claudius Celsus,

Claudius Apollinarius, Asclepiades (servus villicus) et Lucensia, Sergillianus,

Apollonius Diomedis, L. Attienus Iulianus, Mallia Aemiliana domo Roma, Anicetus.

Among these, there are Roman citizens (Tib. Claudius Vitulus and sons, L.

Attienus Iulianus, Mallia Aemiliana), as well as peregrines (Sergillanus,

Apollonius Diomedis) and slaves (Asclepiades, Anicetus). Obviously,

the cult of Diana and Apollo, accompanied by Leto, permeated all social and

professional classes in Montana. The phenomenon was due undoubtedly to intensive

contacts with Eastern-Greek territories, but it is very likely that it was

also strongly rooted in local tradition. An echo of this tradition is to be

discerned in the cognomen of a person who erected a monument to Diana and Apollo

(Diis sanctis Dianae Reginae et Apolloni Phoebo), Iulius Mucazenus,

who was a beneficiarius consularis. Mucazenus is a Thracian name,

hence the founder of the monument must have been a Romanized Thracian cultivating

a tradition of worshipping Apollo.

The rich pantheon of Montana, which incorporated cults popular in the eastern

part of the Roman Empire and occurring also in territories inhabited by the

Thracians (Zeus, Hera, Dionysus, Asklepios, Hermes, Heros etc.), as well as

the worship of the Roman state gods (Jupiter, Juno) and others (Silvanus, Silvestris),

is testimony to an interesting phenomenon of integration, that is, a mixing

of local religious customs with Roman cults.

Troesmis in Dobruja on the Danube, located in a spot where the river

turns toward the Black Sea, also constitutes an interesting object of research,

primarily because there is no doubt that a pre-Roman settlement called Troesmis,

mentioned by Ovid, had existed a short distance away from a fortress of the legio

V Macedonica established there under Trajan. This settlement constituted

an entirely separate unit from the castra legionis and canabae

legionis (cf.  Novae ).

The population was referred to in the sources as Troesmenses, in

contrast to the canabenses, or inhabitants of the canabae, which

were developing by the fortress walls. It has been said already that the

inhabitants of this pre-Roman settlement were organized into a civitas,

which formed the municipium Troesmense in the second half of the

second century, in synoikism with the canabae legionis.

Novae ).

The population was referred to in the sources as Troesmenses, in

contrast to the canabenses, or inhabitants of the canabae, which

were developing by the fortress walls. It has been said already that the

inhabitants of this pre-Roman settlement were organized into a civitas,

which formed the municipium Troesmense in the second half of the

second century, in synoikism with the canabae legionis.

A reconstruction of the religious cults of this civitas Troesmensium remains

a difficult matter. It may be assumed that the autochthonous population was

quickly dominated by new settlers, a process that is fully reflected in the

quoted name of decurio Troesmensium, as well as in the designation c(ives)

R(omani) Tr[oesmi consist(entes)]. Neither is it surprising that virtually

all the religious dedications are to Iovi Optimo Maximo. Exceptions

include a personification of Honos, a dedication to Sol, a syncretic (with

Jupiter) cult of Liber and Sarapis. Yet these are exclusively foreign cults

implanted by the newcomers. The beliefs of the autochthonous population escape

our understanding.

One more observation comes to mind: most of the dedications to Jupiter are

at the same time addressed to the reigning emperor: pro salute imperatoris.

Hardly surprising considering that the founders of the dedications were settlers

with Roman citizenship (cives Romani consistentes), for whom this

was a way of demonstrating their ties with Roman statehood, in similarity to

the inhabitants of the canabae. Undoubtedly, a collective manifestation

of belief in Jupiter and the emperor (tantamount to the Roman state) was an

element integrating the local community, which was often enough of varied geographical

and ethnic provenance. It was simultaneously a specific form of demonstrating

loyalty to the Imperium Romanum.

- D. Detschew, Die thrakischen Sprachreste, Wien 1976

- E. Dorutiu-Boila, Territoriul militar al legiunii V Macedonica la Dunarea

de Jos, Studii si Cercetari de Istorie Veche 23, 1972, 45-62

- A. Mócsy, Gesellschaft und Romanisation in der römischen Provinz

Moesia superior, Budapest 1970

- A. Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, London 1974

- L. Mrozewicz, Rozwój ustroju municypalnego municypalnego postepy romanizacji

w Mezji Dolnej, Poznan 1982

- F. Papazoglu, The Central Balkan Tribes in Pre-Roman Times, Amsterdam 1978

- V. Velkov, Roman Cities in Bulgaria. Collected studies, Amsterdam 1980

- V. Velkov (ed.), Montana, I, Sofia 1987

- V. Velkov, G. Aleksandrov, Epigrafski pametnici ot Montana i rajona, Montana

1994 (= Montana, vol. 2)

(not yet available)