Luxeuil

Lehen

"Schwäbische Ware"

"Helvetische Ware"

Heiligenberg

Rheinzabern

Mould finds

in Germania Superior

Summary

Literature

At the end of the 1st Century BC, an innovative ceramic industry using moulds

and double-chamber and muffle kilns was developed in Italy. It conquered markets

in many Roman provinces in the Mediterranean. Also the huge Samian production

centre in southern

Gaule achieved a similar commercial success. Already at the end of the 1st

Century AD, new Samian manufacturers established themselves in Eastern Gaule.

In the 2nd Century AD, similar production sites were started in the Raetia

and the Germanic provinces. Apparently, province boundaries

didn't play a role in the distribution of Samian.

At the end of the 1st Century BC, an innovative ceramic industry using moulds

and double-chamber and muffle kilns was developed in Italy. It conquered markets

in many Roman provinces in the Mediterranean. Also the huge Samian production

centre in southern

Gaule achieved a similar commercial success. Already at the end of the 1st

Century AD, new Samian manufacturers established themselves in Eastern Gaule.

In the 2nd Century AD, similar production sites were started in the Raetia

and the Germanic provinces. Apparently, province boundaries

didn't play a role in the distribution of Samian.

There were several manufacturing sites for decorated Samian in the province of Germania Superior.

Little is known about the production centre of Luxeuil and it was hitherto only presented in one publication. The distribution of its Samian is currently only derivable from only a few sites outside the production site. The southern part of Germania Superior seems to have been the preferred distribution area.

Already in an early stage of the Samian research did mould fragments and waisters point at the existence of a Samian production site at Lehen nearby Freiburg. But it was only thanks to the publication of H.U. Nuber in 1989 that a preliminary overview on the distribution of this material was achieved.

The main potter Giamillus, whose name was found being stamped in moulds, had

via its figure types close connections to the production site in Luxeuil.

Although the Lehen ware is not known from dated sites, it can be dated because

of its stylistic parallels. The similarity of decoration zones with the decorated

ware from the production centres in central Gaule, such as Martres-de-Veyre

and Lezoux, suggest a dating in the first half of the 2nd century AD.

There were several Roman Samian production centres at Kräherwald, Nürtingen and

Waiblingen, located only a few kilometres apart from each other along the Roman

street from Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt to the Vorderen Limes. At the moment, there

are no reasons to consider these potteries as being independent from each other.

For that reason, this production group is described as "schwäbische Ware".

The distribution of "Schwäbische Ware" is

concentrated on the Vorderen Limes. Nevertheless, several finds along the Danube

suggest that the marketing was not limited to only one province. Also the assumed

custom border of the Western quadragesima Galliarum at the Inn was apparently

not a hindrance for a selling these products towards Noricum and Pannonia.

The dating of these workshops depends heavily on the moving of the Vorderen

Limes further towards the North and the abandonment of the Hinteren Limes around

155/160 AD. Because Waiblingen is situated between both frontier fortifications,

the pottery installations can only have been constructed after the establishment

of the Vorderen Limes around 155/160 AD.

.

Clear evidence for Samian production has been found at Nürtingen during building

activities in 2003 . Complete moulds, waisters and kiln-pads are proofs for

a fully equipped Samian production site. The mouldmaker Verecundus is traceable

by several different dies he used for stamping moulds.

Clear evidence for Samian production has been found at Nürtingen during building

activities in 2003 . Complete moulds, waisters and kiln-pads are proofs for

a fully equipped Samian production site. The mouldmaker Verecundus is traceable

by several different dies he used for stamping moulds.

In

Neuhausen auf den Fildern, which is only 6 kilometres away from Nürtingen,

several mould fragments have been discovered in a cement floor.

Because of the similarities with decorations found at Nürtingen, it is difficult

to avoid the conclusion that these mould fragments have been produced in Nürtingen.

In

Neuhausen auf den Fildern, which is only 6 kilometres away from Nürtingen,

several mould fragments have been discovered in a cement floor.

Because of the similarities with decorations found at Nürtingen, it is difficult

to avoid the conclusion that these mould fragments have been produced in Nürtingen.

Nearby Waiblingen, in the area called "Bildstöckle", traces of a Roman ceramic industry have been found already in the 19th Century.

Extensive excavations in the year 1967 proofed that the finds were related

to a pottery village which was entirely dedicated to pottery production. Up

to 31 pottery kilns have been excavated. Additionally, not only moulds but

also figure dies for decorating moulds were discovered..

Nearby Waiblingen, in the area called "Bildstöckle", traces of a Roman ceramic industry have been found already in the 19th Century.

Extensive excavations in the year 1967 proofed that the finds were related

to a pottery village which was entirely dedicated to pottery production. Up

to 31 pottery kilns have been excavated. Additionally, not only moulds but

also figure dies for decorating moulds were discovered..

The potter Reginus was found to have been the dominating mould maker. Apart from

that, other stylistically independent mould series and figure types of Domitianus

und Marinus have been found.

The relations between the Swabian Reginus and the Reginus who was producing at

Heiligenberg are giving a hint for the dating of Waiblingen. It is conceivable,

that the Heiligenberg Reginus at first tried to start up business in the Swabian

area, before he moved to Rheinzabern.

Already at the beginning of the 20th Century moulds and kiln-pads have been found

during prospections at the Stuttgart Kräherwald. They were published by R.

Knorr. On one of the kild-pads traces of a stamp of Sedatus are visible, who

has also worked at Rheinzabern. Like in Waiblingen, Reginus was also in this

pottery active with a figure type repertoire strongly connected to Heiligenberg

and Rheinzabern.

Already at the beginning of the 20th Century moulds and kiln-pads have been found

during prospections at the Stuttgart Kräherwald. They were published by R.

Knorr. On one of the kild-pads traces of a stamp of Sedatus are visible, who

has also worked at Rheinzabern. Like in Waiblingen, Reginus was also in this

pottery active with a figure type repertoire strongly connected to Heiligenberg

and Rheinzabern.

Two large Samian manufactories are known from southern Germania Superior. On

n the peninsula Bern-Enge and in Baden as well, decorated Samian has been produced

in large quantities. When looking at the distribution of these wares, a sharp

division into two parts of the Helvetian market is clearly visible: whereas

the products from Baden have been sold mainly towards in Western directions,

the pottery from Bern-Enge was principally marketed towards the North and East:

Stylistically, the Helvetian products are not orientating themselves towards

the large manufacture of Rheinzabern, but towards the Raetian Samian industry

of Westerndorf. The vague dating ideas about the Bern-Enge and Baden production

period (at the end of the 2nd Century / beginning of the 3rd century) are in

correspondence with this.

.

During the excavations of R. Forrer at the beginning of the 20th Century, large

pottery installations with several kilns have been found. The extensive Samian

has been published along general lines in 1911.

During the excavations of R. Forrer at the beginning of the 20th Century, large

pottery installations with several kilns have been found. The extensive Samian

has been published along general lines in 1911.

The relation between the Heiligenberg pottery and the ca. 150 AD simultaneously

founded manufactories in Rheinzabern and Waiblingen is still not very clear.

Indisputable is at least, that the Heiligenberg Reginus was also active in

Waiblingen. It can also be taken for granted, that the Heiligenberg potter

Ianus was the same whom we know from the starting period in Rheinzabern. The

close relation between the Samian manufactories in Heiligenberg and Rheinzabern

is also clearly visible in the habit to stamp decorated pots on the rim. This

practice was widely in use in Heiligenberg and during the early period of Rheinzabern.

As an example, the potter Constans did not only in Heiligenberg, but also in

Rheinzabern stamp rims of decorated ware with his name.

The decorate ware in Heiligenberg was largely made by only a few mould makers:

Ianus, F-Meister, Reginus und Ciriuna. Recent chemical-mineralogical analysis

has shown that the decorated ware of Verecundus, which was found at Heiligenberg,

cannot have been produced there. Also the theory of R. Forrer, that Ittenweiler

was an independent production site must nowadays be rejected. According to

the same chemical-mineralogical analysis, the allegedly in Ittenweiler produced

wares must have been produced in Heiligenberg.

The decorate ware in Heiligenberg was largely made by only a few mould makers:

Ianus, F-Meister, Reginus und Ciriuna. Recent chemical-mineralogical analysis

has shown that the decorated ware of Verecundus, which was found at Heiligenberg,

cannot have been produced there. Also the theory of R. Forrer, that Ittenweiler

was an independent production site must nowadays be rejected. According to

the same chemical-mineralogical analysis, the allegedly in Ittenweiler produced

wares must have been produced in Heiligenberg.

The distribution of Samian pottery produced in Heiligenberg is remarkable closely

related to the Vordere Limes, which was established 155/160 AD. It is hardly

accidental that the nearby the Vordere Limes established pottery in Waiblingen

was initiated by the workshop of Reginus in Heiligenberg.

The distribution of Samian pottery produced in Heiligenberg is remarkable closely

related to the Vordere Limes, which was established 155/160 AD. It is hardly

accidental that the nearby the Vordere Limes established pottery in Waiblingen

was initiated by the workshop of Reginus in Heiligenberg.The largest Samian manufacturing site in Germania Superior was situated along

the long-distance road from Strasbourg to Speyer. It supplied between 150/160

AD up to 260 AD large parts of the North-Western Roman Empire.

A section of the 1974-1993 excavation results is showing a classic road vicus

with stripe houses orientated parallel to the main road. The more remote areas

further away from the main road were clearly less structured.

Already during the 1st century AD, the clay resources nearby Rheinzabern were exploited. The road vicus Tabernae Rhenanae with its typical stripe houses was in the 1st century AD a production site for tiles of the Legio IV Macedonica and Legio XXII Primigenia. At the end of the 1st century AD, the legions Legio I Adiutrix, Legio XIV and Legio XXI Rapax made tiles in the same place. These legions were stationed in Mainz. Whether the pottery village was under military administration is unknown. A military camp has until now not been found..

Apart from tile production, also coarse ware has been produced.

In the middle of the 2nd century AD several parcel structures were not considered anymore and pottery installation were build on top of them. It is yet unclear whether this happened only locally or in the whole village.

The manufacturing of decorated Samian started in Rheinzabern around 150 AD. With the aid of moulds, decorated vessels could be produced in series. The technique of 2 room kilns, which technique was transferred from Italy, allowed for a separating of smoke and ceramic during the firing and also for extremely high firing temperatures of more than 1000 degrees.

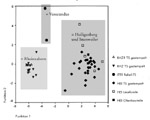

Statistical studies proofed that the Rheinzabern potters were organised in 7 groups. They can be called Jaccard-Gruppen. Some potters could switch between the groups.

Rheinzabern Samian was distributed from England to the Black Sea. The dots on

the map are only showing the presence of Rheinzabern Samian. They do not present

frequencies. Based on the quantities behind each dot, the distribution in England

and Romania can be considered as a periphery market.

When considering the distribution map of Rheinzabern Samian, it is clear that

there have been several gravity centres in Barbaricum, which cannot be contributed

to research focussing on certain areas.

The remarkable strong concentration in Friesland is possibly related to the

enhancement of the coastal defence systems in Zeeland, Belgium and England

during the reign of the Usurpator Carausius. The strongholds in Aardenburg,

Oudenburg and Shadwell are clear indications of an intensified military presence

and with that a strong pointer towards where the money went in this area at

that time. At the same time, the actual Limes in Germania Inferior was hardly

supplied anymore with Samian.

Some find contexts in the vicinity of Leuna-Hassleben from period C1

brought considerable quantities of Samian produced in Rheinzabern. The fact

that many gold coins from the same period have been found in this region strongly

points towards a special relationship between the tribal people near Leuna-Hassleben

and the Roman Empire. This relationship must not have been of a friendly nature,

as finds from the Mainfranken seem to indicate. The Germanic settlements in

Mainfranken delivered also large quantities of Samian produced in Rheinzabern.

But in this case, the Germani from this region were considered as hostile

by the Romans, since the adjoining Limes section was enforced with police stations

of the benificarii.

On the other hand are the remarkable quantities found in Slovakia and Pannonia

directly related to the military campaigns of the Marcomannic wars and the

presence of the Roman emperors in Aquincum until 212 AD. The majority of the

decorated Samian found in this region dates is datable in this period.

The significant find concentration in central Poland cannot be explained at the moment. Because the same decoration series are involved as those found in Slovakia and Pannonia, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that there must have been a relation between this central Polish region and the Marcomannic wars and the presence of the emperors Septimus Severus und Caracalla in Pannonia afterwards.

Putting things together concerning the distribution of Rheinzabern Samian, one can clearly see a development in its distribution patterns. The early products were mainly sold in the mid-Neckar area and Raetia. The vessels made in the middle production period were preferably merchandised into the Pannonia area and its adjacent Barbaricum. The latish Rheinzabern Samian was mainly distributed in the Wetterau and towards the North Sea coast.

Several mould fragments have been found outside the manufacturing sites in the

Germanic provinces and in Raetia as well. By far the most mould fragments

could be registered in the province Germania Superior. This could have

been caused

by the high concentration of production sites in this province.

A general impression when looking at the distribution of mould finds is that

they usually occur within the proper distribution area of the production site.

The only exception is a mould

find in Kempten in the province Raetia. All this evidence suggests that these pieces were transported within the context

of the regular ceramic trade and can not be taken as indications for the establishment

of new Samian potteries in hitherto uncovered distribution markets.

The provenance of several mould finds is unclear. This concerns specifically large mould fragments in which mould stamps are completely preserved. Especially this category can be found regularly in old museum basement collections with uncertain provenance. Therefore it seems logic that these pieces came in exchange or as a present from the Rheinzabern excavations in the beginning of the 20th Century. Similar mould finds are known the magazines from Lyon, Nantes and Bordeaux.

The following list contains the mould fragments hitherto found outside the Samian production sites. List 2 contains finds from museum basement collections with unclear provenances. A third list shows moulds in fine ware technique.

In very few cases fine ware has been produced out of Samian moulds. These indirect evidence for the presence of Samian moulds can be summarised in a fourth list.

To conclude: the foundation of Samian manufacturies in Germania Superior and Raetia happened along a very clear chronological line from the West towards the East. The earliest newly started Samian production centres were started in Luxeuil (120-140 n.Chr.) and Heiligenberg (140-160 n.Chr.). A connection between Heiligenberg and the military activities at the Vordere Limes can only partly be assumed for Heiligenberg. On the contrary, in the case of Waiblingen, this connection is very clear related to the forwarding of the Limes in 155/160 n.Chr. The marketing area of the Samian production centres in Schwabegg and Westerndorf were orientated much further towards the East, were between 170 and 220 AD a large economic potential appeared in the context of the Marcomannic wars and the presence of several emperors in the middle Danube area.

K. Roth-Rubi, La production de terre sigillée en Suisse aux IIe et IIIe S. Problèmes de définition. In: C. Bémont / J.-P. Jacob (ed.), La terre sigillée gallo-romaine. Lieux de production du Haut-Empire: implantations, produits, relations. Documents d'Archéologie Française 6, 269-273.

Kaiser 2005, 403-408; Luik 1996, 161-162 Fußnote 504; Luik 2005, 129-133; Luik 2005, 19-24; Simon 1977, 464-473; Simon 1984, 471ff.

Zusammenfassend für den Vorderen Limes: Biegert / Lauber /Kortüm 1995, 653ff.

Bemmann 1994, 98; Eschbaumer 1990, 265; Fischer 1990, 44; Fritsch 1910a; Fritsch

1910b, Taf. 7-10; Fritsch 1913; Furger/Deschler-Erb 1992, Taf. 70, 18/9; Gaubatz-Sattler

1995,

145ff;

Gaubatz-Sattler

1999; Grönke/Weinlich 1991,

51;

Groh

/ Sedlmayer 2006, 252;

Hartmann 1981, 19; Jütting 1995, 185; Juhász 1935, kép

XII;

Jung / Schücker 2006, Tab. 6; Karnitsch

1959,

244-246;

Karnitsch

1960, 24; Karnitsch 1971, 144;

Luik

1996,

151f.; Mayer-Reppert 2003, 468; Mayer-Reppert 2006; Menke 1974, 150; Müller

1979, 45; Ortisi 2000, 56; Pferdehirt 1983, 361; Pferdehirt 2003, 227; Sakař

1956,

56;

Schmid 2000; Schönberger / Simon 1966, nr. 330; Simon 1970, 99; Simon 1973,

94; Simon 1976, 49; Simon 1978, 25; Simon 1983; Spitzing 1988, 71; Teichner

1994, 192;Thiel

2005,

Taf.

30; Urner-Astholz 1942;

Urner-Astholz 1946; Wagner-Roser 1999; Walke 1965, Taf. 21; Zanier 1992,

116.

Mayer-Reppert 2006, 218; H.U. Nuber, A. Giamilus - ein Sigillatatöpfer aus dem Breisgau. Archäologische Nachrichten aus Baden 42, 1989, 3-9.

Lerat / Y. Jeannin 1960, Fig. 10; Mayer-Reppert 2006, 219.

Droberjar 1991; Erdrich 2001; Gabler / Vaday 1986; Gabler / Vaday 1992; Hansen 1987; Mayer-Reppert 2006 218; Mees 2002, 149ff.; Peschek 1978, 75ff; Popilian 1973; Tyszler 1999.

S. Biegert: Chemische Analysen zu glatter Sigillata aus Heiligenberg und Ittenweiler. In: B. Liesen / U. Brandl (Hrsg.), Römische Keramik: Herstellung und Handel. Xantener Berichte 13 (2003) 7-27.

H. Bemmann, Terra-Sigillata-Funde aus der Töpfersiedlung in Weißenthurm, Kr. Mayen-Koblenz, Sammlung Urmersbach. Pellenz Museum 6 (Nickenich 1994).

H. Bernhard, Terra Sigillata und Keramikhandel. In: L. Wamser (Hrsg.), Die Römer zwischen Alpen und Nordmeer. Zivilisatorisches Erbe einer europäischen Militärmacht (Mainz 2000) 138-141.

A. Bräuning / Chr. Dreier / J. Klug-Treppe, Riegel - Römerstadt am Kaiserstuhl. Archäologische Informationen aus Baden-Württemberg 49 (Freiburg 2004).

S. Biegert / J. Lauber / K. Kortüm, Töpferstempel auf glatter Sigillata vom vorderen/westrätischen Limes. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 20, 1995, 547-666.

W. Czysz, Der Sigillata-Geschirrfund von Cambodunum-Kempten. Berichte RGK 63, 1982, 343-345.

B. Pferdehirt, Reliefsigillata und Stempel auf glatter Sigillata aus Heldenbergen. In: W. Czysz, Heldenbergen in der Wetterau. Feldlager, Kastell, Vicus. Limesforschungen 27 (Mainz 2003) 216-230.

E. Droberjar, Terra Sigillata in Mähren. Funde aus germanischen Lokalitäten. Mährische archäologische Quellen (Brno 1991).

Chr. Ebnöther, Der römische Gutshof in Dietikon. Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 25 (Zürich 1995).

M. Erdrich, Rom und die Barbaren: das Verhältnis zwischen dem Imperium Romanum und den germanischen Stämmen vor seiner Nordwestgrenze von der späten römischen Republik bis zum gallischen Sonderreich. Römisch-germanische Forschungen 58 (Mainz 2001).

P. Eschbaumer, Das römische Nassenfels und sein Umland (Mikrofiche-Ausgabe, München 1990).

Th. Fischer, Das Umland des römischen Regensburg. Münchner Beiträge zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte 42 (München 1990).

F. Fremersdorf, Die Herstellung von Relief-Sigillata im römischen Mainz. Mainzer Zeitschrift 44/49, 1949-1954, 34-38.

O. Fritsch, Die Terra-Sigillata-Funde der Städtischen Historischen Sammlungen in Baden-Baden (Baden-Baden 1910).

O. Fritsch, Römische Gefäbe aus Terra Sigillata von Riegel am Kaiserstuhl. Veröffentlichungen des Karlsruher Altertumsverein 4 (Karlsruhe 1910).

O. Fritsch, Terra-Sigillata-Gefässe, gefunden im Grobherzogtum Baden (Karlsruhe 1913).

A.R. Furger/S. Deschler-Erb (Hrsg.), Das Fundmaterial aus der Schichtenfolge beim Augster Theater. Typologische und osteologische Untersuchungen zur Grabung Theater-Nordwestecke 1986/87. Forschungen in Augst 15 (Augst 1992).

D. Gabler / A.H. Vaday, Terra Sigillata im Barbaricum zwischen Pannonien und Dazien. Fontes Archaeologici Hungariae (Budapest 1986).

D. Gabler / A.H. Vaday, Terra Sigillata im Barbaricum zwischen Pannonien und Dazien. 2. Teil. Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44, 1992, 83-160.

A. Gaubatz-Sattler, Die Villa rustica von Bondorf (Lkr. Böblingen). Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 51 (Stuttgart 1994).

A. Gaubatz-Sattle, Sumelocenna.Geschichte und Topographie des römischen Rottenburg am Neckar nach den Befunden und Funden bis 1985. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 71 (Stuttgart 1999).

E. Grönke/E. Weinlich, Die Nordfront des römischen Kastells Biricana-Weissenburg. Die Ausgrabungen 1986/1987. Kataloge der Prähistorischen Staatssammlung 25 (Kallmünz 1991).

S. Groh / H. Sedlmayer, Forschungen im Vicus Ost von Mautern-Favianis.Die Grabungen der Jahre 1997–1999 (Wien 2006)

U.L. Hansen, Römischer Import im Norden. Warenaustausch zwischen den Römischen Reich und dem freien Germanien während der Kaiserzeit unter besonderer Berücksichtigung Nordeuropas (Køpenhavn 1987) 179-191.

H.H. Hartmann, Die Reliefsigillata aus dem Vicus Wimpfen im Tal (Kreis Heilbronn). In: W. Czysz/H. Kaiser/M. Mackensen/G. Ulbert, Die römische Keramik aus dem Vicus Wimpfen im Tal. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 11 (Stuttgart 1981) 190-253.

I. Jütting, Die Kleinfunde aus dem römischen Lager Eining-Unterfeld. Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter 60, 1995, ...-...

G. Juhász, A brigetoi terra sigillaták (Die Sigillaten von Brigetio). Dissertationes Pannonicae 2,2 (Budapest 1935).

P. Jung / N. Schücker, 1000 gestempelte Sigillaten aus Altbeständen des Landesmuseum Mainz. Universitätszur prähistorischen Archäologie 132 (Bonn 2006).

H. Kaiser, Zum Beispiel Waiblingen. Römische Töpfereien in Baden-Württemberg. In: S. Schmidt / M. Kempa, Imperium Romanum. Roms Provinzen an Necakr, Rhein und Donau (Stuttgart 2006) 403-408.

P. Karnitsch, Die Reliefsigillata von Ovilava (Wels, Oberösterreich). Schriftenreihe des Institutes für Landeskunde von Oberösterreich 12 (Linz 1959).

P. Karnitsch, Die Sigillata von Veldidena (Wilten-Innsbruck). Archäologische Forschungen in Tirol 1 (Innsbruck 1960).

P. Karnitsch, Sigillata von Iuvavum (Salzburg). Die reliefverzierte Sigillata im Salzburger Museum Carolino Augusteum. Salzburger Museum Carolino Augusteum Jahresschrift 16, 1970 (Salzburg 1971).

K. Kuzmová / P. Roth, Terra Sigillata v Barbariku, nálezy z germánskych sídlisk a pohrebísk na území Slovenska. Materialia Archaeoglogica Slovaca 9 (Nitra 1988).

K. Kuzmová, Terra Sigillata im Vorfeld des nordpannonischen Limes (Südwestslowakei). Archaeologica Slovaca Monographiae 16 (Nitra 1997).

L. Lerat / Y. Jeannin. La céramique sigilée de Luxeuil (Paris 1960).

M. Luik, Köngen - Grinario I. Topographie, Fundstellenverzeichnis, ausgewählte Fundgruppen. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 62 (Stuttgart 1996).

M. Luik, "Schwäbischer Fleiß" in der Antike. Die neu entdeckte Sigillata-Manufaktur von Nürtingen (Kreis Esslingen). Nachrichtenblatt der Landesdenkmalpflege Baden-Württemberg, 3/2005, 129-133 (online Ausgabe)

M. Luik, Eine neue TS Manufaktur von Nürtingen (Kreis Esslingen, Baden-Württemberg). RCRF Acta 39, 2005, 19-24.

R. Knorr 1905, Die verzierten Terra sigillata-Gefäße von Cannstatt und Köngen (Stuttgart 1905).

R. Knorr, Die verzierten Terra-Sigillata-Gefässe von Rottweil (Stuttgart 1907).

K. Kortüm,

PORTUS – Pforzheim.

Untersuchungen zur Archäologie und Geschichte in römischer Zeit

Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Stadt Pforzheim 3 (Pforzheim 1995).

K. Kuzmová / P. Roth, Terra sigillata v Barbariku. Nálezy z germánskch sídlisk a pohrebísk na území slovenska. Materialia Archaeologica Slovaca 9 (Nitra 1988)

K. Kuzmová, Terra Sigillata im Vorfeld des nordpannonischen Limes (Südwestslowakei). Archaeologica Slovaca Monographiae 16 (Nitra 1997).

P. Mayer-Reppert, Römische Funde aus Konstanz. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 27, 2003, 441-554.

P. Mayer-Reppert, Die Terra Sigillata aus der römischen Zivilsiedlung von Hüfingen-Mühlöschle (Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis) (Microfiche, Remshalden 2006).

A.W. Mees, Organisationsformen römischer Töpfer-Manufakturen am Beispiel von Arezzo und Rheinzabern : unter Berücksichtigung von Papyri, Inschriften und Rechtsquellen. Monographien Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Forschungsinstitut für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 52 (Mainz 2002).

H. Menke, Reliefverzierte Sigillata aus Karlstein-Langackertal, Ldkr. Berchtesgaden. Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter 39, 1974, 127-160.

G. Müller, Römische Einzelfunde aus Neuss.Beiträge zur Archäologie des römischen Rheinlands 2. Rheinische Ausgrabungen 10 (Düsseldorf 1971).

G. Müller, Ausgrabungen in Dormagen 1963-1977. Rheinische Ausgrabungen 20 (Köln 1979).

S. Ortisi, Die Stadtmauer der raetischen Provinzhauptstadt Aelia Augusta - Augsburg. Die Ausgrabungen Lange Gasse 11, Auf dem Kreuz 58, Heilig-Kreuz-Stra. 26 und 4. Augsburger Beiträge zur Archäologie 2 (Augsburg 2000).

G. Peschek, Die germanischen Bodenfunde der römischen Kaiserzeit in Mainfranken. Münchner Beiträge zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte 27 (München 1978) .

B. Pferdehirt, Zur Sigillatabelieferung von Obergermanien. Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums 30, 1983, 359-381.

G. Popilian, La céramique sigillée d'importation découverte en Oltenie. Dacia 27, 1973, 197-216.

H.G. Rau, Die römische Töpferei in Rheinzabern, die Werkstätten (Rheinzabern 1987).

V. Sakař, Terra sigillata v českých nálezech. Památky archaeologické 47, 1956, 52-69.

W. Schleiermacher, Cambodunum-Kempten, eine Römerstadt im Allgäu (Bonn 1972).

A. Schaub, Markomannenkriegszeitliche Zerstörungen in Sulz am Neckar - Ein tradierter Irrtum. Bemerkungen zu reliefverzierter Terra Sigillata vom Ende des zweiten Jahrhunderts. In: H. Friesinger / J. Tejral / A. Stuppner (Hrsg.), Markomannenkriege - Ursachen und Wirkungen (Brno 1994) 439-444.

J. Schmid (Hrsg.), Gontia. Studien zum römischen Günzburg (München 2000).

H. Schönberger / H.-G. Simon, Die mittelkaiserzeitliche Terra Sigillata von Neuss. Limesforschungen 7 (Berlin 1966).

H.-G. Simon, Die römischen Fund aus den Grabungen in Groß-Gerau 1962/63. Saalburg-Jahrbuch 22, 1965, 38-99.

H.-G. Simon, Zur Anfangsdatierung des Kastells Pförring. Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter 35, 1970, 94-105.

H.-G. Simon, Bilderschüsseln und Töpferstempel auf glatter Ware. In: D. Baatz (Hrsg.), Kastell Hesselbach und andere Forschungen am Odenwaldlimes. Limesforschungen 12 (Berlin 1973) 89-96.

H.-G. Simon, Terra Sigillata: Bilderschüsseln und Töpferstempel auf glatter Ware. In: D. Baatz, Das Kastell Munningen im Nördlinger Ries. Saalburg Jahrbuch 33, 1976, 37-53.

H.-G. Simon, Neufunde von Sigillata-Formschüsseln im Kreis Esslingen. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 3, 1977, 464-473.

H.-G. Simon, Römische Funde aus Theilenhofen. Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter 43, 1978, 25-56.

H.-G. Simon, Terra Sigillata. In: H. Schönberger/H.-G. Simon, Die Kastelle in Altenstadt. Limesforschungen 22 (Berlin 1983) 71-104.

H.-G. Simon, Terra Sigillata aus Waiblingen. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 9, 1984, 471-546.

R. Sölch, Die Terra-Sigillata-Manufaktur von Schwabmünchen-Schwabegg. Materialhefte zur bayerischen Vorgeschichte, Reihe A, 81 (Kallmünz/Opf. 1999).

T. Spitzing, Die römische Villa von Lauffen a.N. (Kr. Heilbronn). Materialhefte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 12 (Stuttgart 1988).

F. Teichner, Zur Chronologie des römischen Obernburg a. Main, Lkr. Miltenberg, Unterfranken. Bericht der Bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege 30/31, 1989/90 (1994) 179-230.

A. Thiel, Das römische Jagsthausen. Kastell, Vicu und Siedelstellen des Umlandes. Materialhefte zur Archäologie in Baden-Württemberg 72 (Stuttgart 2005).

L. Tyszler, Terra Sigillata na ziemiach Polski. Acta Archaeologica Lodziensia 43/44 (Łódż 1999).

H. Urner-Astholz, Die römerzeitliche Keramik von Eschenz-Tasgetium. Thurgauische Beiträge zur Vaterländischen Geschichte 78, 1942, 7-156.

H. Urner-Astholz, Die römerzeitliche Keramik von Schleitheim-Juliomagus. Schaffhauser Beiträge zur Vaterländischen Geschichte 23, 1946, 35-205.

V. Vogel Müller, Ein Formschüsselfragment und ein Bruchstuck helvetischer Reliefsigillata aus Augst. Jahresberichte aus Augst und Kaiseraugst, 11, 1990, 147-152.

E. Vogt, Terra sigillatafabrikation in der Schweiz. Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 3, 1941, 95-109.

N. Walke, Das römische Donau-Kastell Straubing-Sorviodurum. Limesforschungen 3 (Berlin 1965).

W. J. H. Willems, Romans and Batavians. A Regional study in the Dutch Eastern River Area I. Ber. ROB 31, 1981, 7 ff.

S. Wagner-Roser, Ausgewählte Befunde und Funde der römischen Siedlung Lahr-Dinglingen von 1824-1982. Edition Wissenschaft, Reihe Altertumswissenschaft 3 (Marburg 1999; Mikrofiche).

W. Zanier, Das römische Kastell Ellingen. Limesforschungen 23 (Mainz 1992).